Nothing Gold Can Stay

by Robert Frost

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

Robert Frost wrote a number of long narrative poems like “The Death of the Hired Man,” and most of his best-known poems are medium-length, like his sonnets “Mowing” and “Acquainted with the Night,” or his two most famous poems, both written in four stanzas, “The Road Not Taken” and “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.” But some of his most beloved poems are famously brief lyrics—like “Nothing Gold Can Stay,” which is condensed into only eight lines of three beats each (iambic trimeter), four little rhyming couplets containing the whole cycle of life, an entire philosophy.

“Nothing Gold Can Stay” achieves its perfect brevity by making every word count, with a richness of meanings. At first, you think it’s a simple poem about the natural life cycle of a tree:

“Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.”

But the very mention of “gold” expands beyond the forest to human commerce, to the symbolism of wealth and the philosophy of value. Then the second couplet seems to return to a more conventional poetic statement about the transience of life and beauty:

“Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.”

But immediately after that we realize that Frost is playing with the multiple meanings of these simple, mostly single syllable words—else why would he repeat “leaf” like he’s ringing a bell? “Leaf” echoes with its many meanings—leaves of paper, leafing through a book, the color leaf green, leafing out as an action, as budding forth, time passing as the pages of the calendar turn….

“Then leaf subsides to leaf.”

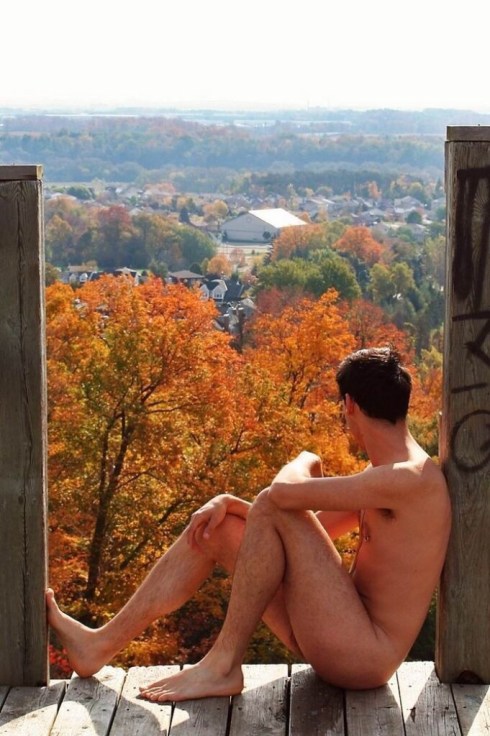

As the Friends of Robert Frost at the Robert Frost Stone House Museum in Vermont point out, the description of colors in the first lines of this poem is a literal depiction of the spring budding of willow and maple trees, whose leaf buds appear very briefly as golden-colored before they mature to the green of actual leaves.

Yet in the sixth line, Frost makes it explicit that his poem carries the double meaning of allegory:

“So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.”

He is retelling the history of the world here, how the first sparkle of any new life, the first blush of the birth of mankind, the first golden light of any new day always fades, subsides, sinks, goes down.

“Nothing gold can stay.”

Frost has been describing spring, but by speaking of Eden he brings fall, and the fall of man, to mind without even using the word. That’s why we chose to include this poem in our seasonal collection of poems for autumn rather than spring.