Category Archives: Art

Coded

Joseph Christian Leyendecker’s life, career, and love is captured in a new film, Coded: The Hidden Love of J.C. Leyendecker, which I watched the other day on Paramount+. The documentary shows Leyendecker’s enduring influence on American culture and LGBTQ+ representation in advertising, as well as the relationship with his partner, Charles Beach, the muse for Leyendecker’s “Arrow Collar Man.”

The use of men as sexy symbols in advertising would not have existed without the influence of Leyendecker’s art. The German-American artist received training in Paris under the French Art Nouveau movement and imported some of this “Modern Style” to United States. His ad illustrations, which leaned into sexualizing his handsome male subjects, made brands like Arrow shirts fly off the shelves while also defining the image of the early 20th-century American man. Many of his illustrations featured intimate gazes between two gentlemen. Often, if there were two gentlemen and a lady, the two men would be focused on each other and not the woman.

Additionally, Leyendecker painted over 400 magazine covers in his career — over 300 alone for The Saturday Evening Post — essentially creating the design template still in use today. His stock took a plunge along with Wall Street following the Great Depression, when shrinking wallets also meant a return to social conservatism. The public turned away from Leyendecker’s eroticized male forms toward Norman Rockwell, a more traditional illustrator who was mentored by Leyendecker.

The image below of an Ivory Soap advertisement from 1900 is one of his early pieces before he met Charles Beach; however, it is a great example of the coded messages in many of his works. Can you spot the “code” in this image? Once you see it, you’ll probably never not see it.

In honor of the (Winter) Olympics beginning this week, I’ll end with this 1932 edition of The Saturday Evening Post. Strangely, the conservative, anti-New Deal, and middle class family orientated publication had what is (to most modern eyes at least) a sexualized ‘gay’ image of the U.S. Olympic Eight on its cover, painted by Leyendecker. This was not the only time that Leyendecker put semi-naked men on a pedestal as you’ve seen in some of his other illustrations.

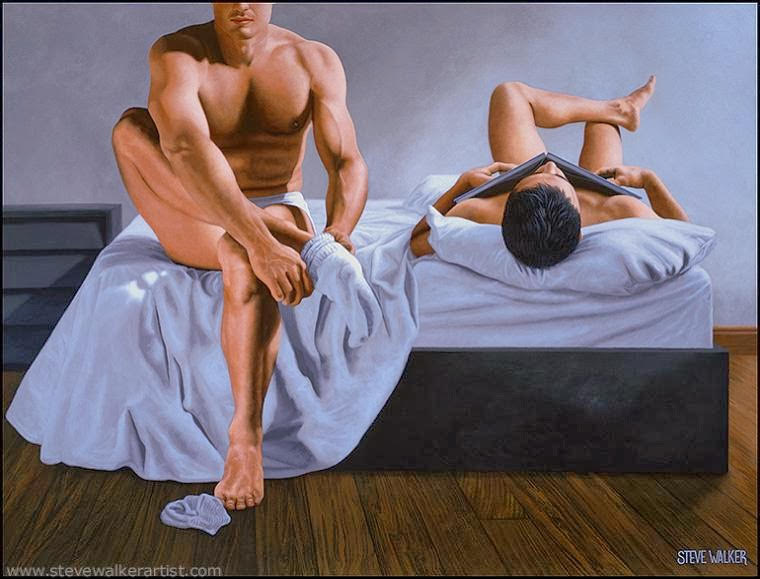

Remembering Steve Walker

Since the beginning of this blog, I have used the 2001 painting “David and Me” by Canadian artist Steve Walker as my profile picture and my avatar. Someday, I may change it to an actually picture of me, but for now it remains. I chose it for what I think is a very good reason. Back in 2006, I spent a month in Italy conducting research for my dissertation. I remember standing in front of and looking up at the remarkable statue of David by Michelangelo much like the guy in the picture, though I don’t think I was wearing a backpack at the time. It was a truly awesome experience. Each time I look at images of the painting I am transported back to that day in the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence. Of course, back then I did have a head full of brown hair with a similar hairstyle. Today, there is much less hair and what I do have left is now nearly completely gray. I don’t have the muscle definition I had back then, and there’s a more weight on my body. The painting has always had a special place in my heart, and I wish I owned an actual print of the image.

Walker passed away at his home in Costa Rica on Jan 4,2012, at age 50. He was best known for his haunting and poignant acrylic portraits of beautiful young men (solo and in pairs), often done in muted shades. “Some colors are very exciting to me,” he once told James Lyman, a Massachusetts gallery owner and Walker’s art executor and trustee. “While others are quite offensive. Painting flesh is very exciting to me because of the huge variations possible within a very small color range.”

According to friends, Walker was strongly influenced by Renaissance Italian artist Caravaggio – especially in his use of shadow to show the contours of the young male form. For his subjects, he chose to paint gay men, depicting the struggles and joys the gay community lived through in his lifetime, from the fight for sexual liberation to the devastation brought about by HIV and AIDS. Walker believed his subjects were universal, touching on themes of love, hate, pain, joy, beauty, loneliness, attraction, hope, despair, life, and death.

As a homosexual, I have been moved, educated, and inspired by works that deal with a heterosexual context. Why would I assume that a heterosexual would be incapable of appreciating work that speaks to common themes in life, as seen through my eyes as a gay man? If the heterosexual population is unable to do this, then the loss is theirs, not mine

—Steve Walker

Walker was an entirely self-taught artist and sold his first painting, Blue Boy in 1990. He painted a second in 1991, called Morning, of two young men in bed after sex. Walker’s paintings were mostly large because he believed that a large image was more appealing and has more impact than a smaller one. As with many artists, Walker was painting the sadness that was in his life. Two of Walker’s partners had died over the years, and his close friend Marlene Anderson says he was lonely. His paintings are about gay life, and the focus of them often depicted sadness and loneliness to reflect the reality that much of anyone’s life is sad and lonely. Walker told a firend that it is rare to find success as an artist, and Walker was happy his work would be his lasting legacy.

I strive to make people stop, if only a moment, think and actually feel something. My paintings contain as many questions as answers. I hope that in its silence, the body of my work has given a voice to my life, the lives of others, and in doing so, the dignity of all people.

—Steve Walker

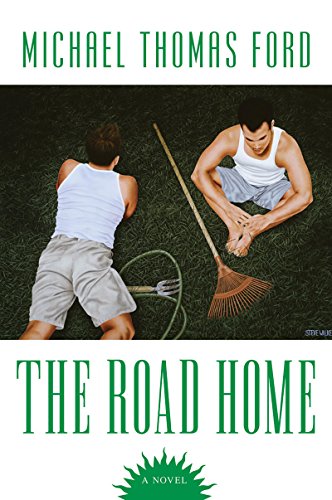

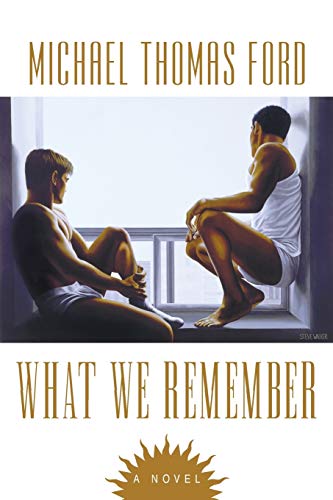

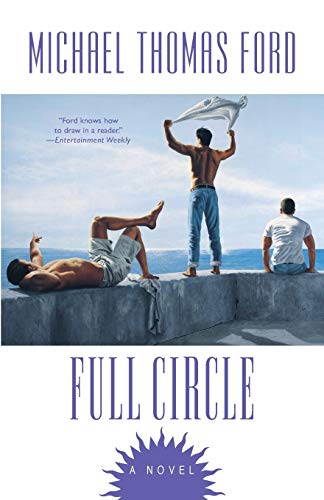

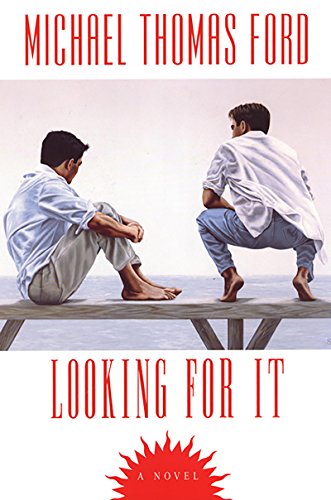

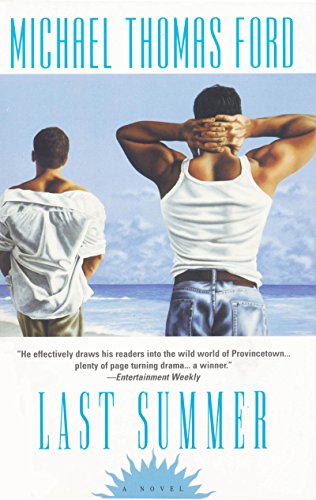

In his lifetime, Walter’s work was exhibited in Toronto, Montreal, Los Angeles, Fort Lauderdale, Provincetown, and Pasadena. Much of the gay community loved Walker’s work and many pieces were sold for several thousand dollars. His art appear on the covers of gay novels, such as American writer Felice Picano’s 1995 epic Like People in History and the late Gordon Anderson’s novel of 1970s Toronto, The Toronto You Are Leaving. His paintings also grace the covers of six books by Michael Thomas Ford: Last Summer, Looking For It, Full Circle, Changing Tides, What We Remember, and The Road Home. Ford describes the book on his website mirroring what has been said about Walker’s art:

Much of my fiction is about what it’s like living as a gay man at this time in history. These six novels look at different aspects of the gay experience. Although they share a cover style, they are not a series, and may be read in any order. Many people ask who the cover artist is. It’s Steve Walker. Steve died in 2012, but his wonderful artwork capturing the lives of gay men remains to remind us of his talent.

Moment of Zen: LGBTQ+ Art, Material Culture & History

A signed copy of the Bruce Weber photograph above, titled Tara and her pal Chris, San Onofre, CA, just sold at Swann Auction Galleries for $4,500. Bruce Weber (born March 29, 1946) is a fashion photographer. He is most widely known for his ad campaigns for Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren, Pirelli, Abercrombie & Fitch, Revlon, and Gianni Versace, as well as his work for Vogue, GQ, Vanity Fair, Elle, Life, Interview, and Rolling Stone magazines.

The auction “LGBTQ+ Art, Material Culture & History” was the gallery’s third annual auction dedicated to the art, material culture, and history of the LGBTQ+ community. The auction brought to market both familiar artists as well as fresh, unusual, and infrequently seen material. Among the art highlights are several original works by Tom of Finland, including two preparatory drawings and a completed, color pencil work, “Home—Secured.” It also included four oil paintings by Hugh Steers—two canvases and two works on paper. Other art and photography included are works by Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, David Wojnarowicz, Nan Goldin, Patrick Angus, Lowell Nesbit, Robert Bliss, Nicole Eisenman, Robert Loughlin, Paul Cadmus, Jean Cocteau, Avel de Knight, Pavel Tchelitchew, Duncan Grant and others.

Boston MFA

The Boston Museum of Fine Arts is amazing. They had a Botticelli exhibit that was truly out of this world. The Venus above is an example of what was there. We also went to the American gallery where they had an exhibit of John Singer Seargent. Wow, that was some beautiful art, such as the nude below.

Homosexuality in Japan’s Edo Period

Japan’s Edo period, stretching from the 17th to 19th century, was characterized by economic growth and a rigid social order, both of which worked together to bolster a before unrealized interest in art, culture, entertainment and, yes, sex.

While most marriages at the time were arranged — and between a man and a woman — sex between two men was not at all uncommon, though often kept out of public view. For the most part, such erotic encounters were allocated to three spheres: red-light style pleasure districts, kabuki theater, and shunga, or erotic art.

Artistic representations of erotic encounters between two men, known as nanshoku, are harder to find in the annals of shunga prints than images of sexually skilled octopi. However, a wildly rare shunga handscroll by artist Miyagawa Choshun, which has been shielded from public view since the 1970s, depicting man-on-man loving, has been recently rediscovered by Bonhams auction house.

“In the strictly regulated society of Edo period Japan, it was not unusual for people to yearn for circumstances and opportunities not afforded them by birth,” Bonhams’ Director of Japanese Art Jeff Olson said in a press statement. “For most, costly visits to the pleasure quarters were out of reach, so illustrated erotica was the next best thing.”

While most shunga prints frame the genitals front and center, nanshoku works focus more on the tender romance of the relationship. Think of them as the soft-core alternative to hardcore porn. The pairings normally consist of an older man and a younger partner, dressed in an ornate kimono and traditional woman’s hairstyle. Artistic depictions often muse on the luxurious details of the young lover’s garments and appearance.

Choshun’s striking handscrolls are at once minimalist in their color-blocked elegance and grandiose in their detailed renderings of kimonos and tricky-looking sexual positions. The lovers are rendered in a gold-tinted, floating world, swallowed up by the fantasy of their own desires.

This article is from the Huffington Post, though slightly edited. To see more of these depictions of Japanese gay erotica (though I’ll be honest, they don’t look too gay to me), you can feast your eyes on these delightfully rare, 17th-century Japanese gay erotica at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/feast-your-eyes-on-these-rare-17th-century-handscrolls-of-japanese-gay-erotica_us_56ec35bfe4b03a640a6a53d5

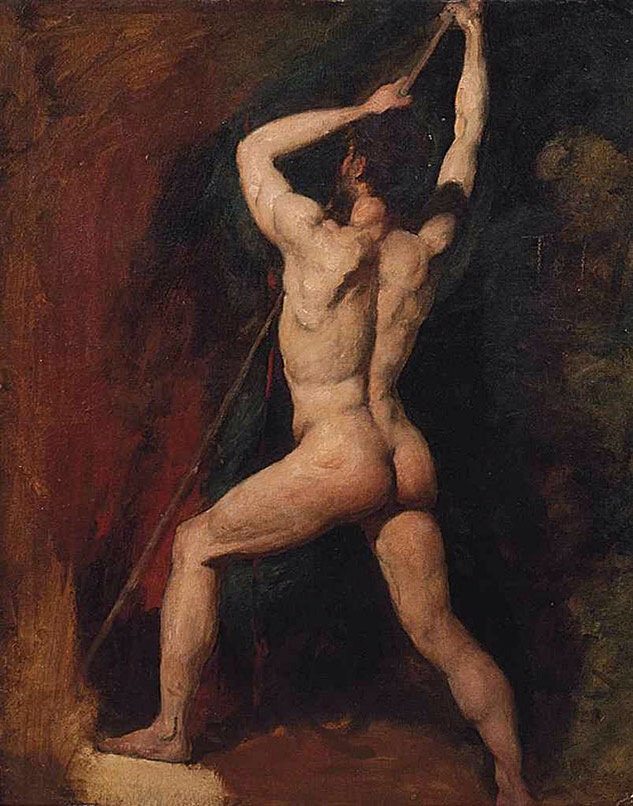

William Etty: Artist and Callipygian Enthusiast

William Etty (1787-1849) is probably the most controversial artists of whom you have probably never heard. A high-minded bachelor whose private life has defied all attempts to unearth smut, Etty was acclaimed in his day but eventually sidelined because of his defiance of moralizing, often hypocritical, critics. He was a shy man and remained a bachelor all his life, which at the time was practically a statement. There is no way to confirm Etty’s sexual orientation since he’s long dead and lived in a time when no one really identified as gay. However, the paintings may speak for themselves. He was a successful Royal Academy artist, but his work fell out of favor after his death. But while he was an active painter he was both admired and condemned for his detailed renderings of the naked human body.

Critics felt he focused too much on the female buttocks, but if you Google Image search for his work, you find a surprisingly large number of male nudes, many with a focus on the male buttocks as well. Seems none of his contemporaries were interested in commenting on that, but it’s obvious that Etty’s was a butt man, no matter his orientation.

Whereas his contemporaries, like J.M.W. Turner changed how people saw art, Etty wanted to change what people saw. Etty broke the rules of decorum by painting humanly realistic nudes rather than idealized gods and goddesses. Most of the criticism questioned the appropriateness of Etty’s female nudes, while the male nudes quite often found praise as “heroic.” Tragically, the critics got personal in their comments, essentially charging Etty with deliberately trying to corrupt the viewing public.

“He is a laborious draughtsman, and a beautiful colourist,” one critic began innocently enough, “but he [Etty] has not taste or chastity of mind enough to venture on the naked truth […] we fear that Mr. E will never turn from his wicked ways, and make himself fit for decent company.” “[T]he spectator can see in [Etty’s female nudes] nothing beyond the portrait of some poor girl who was necessitated to sacrifice the feelings of her sex for bread,” another critic accused. “Nudity is all that the artist has to show us, and when unassociated with anything like incident or sentiment, the spectacle is offensive.” Etty defended himself as an innocent lover of nature’s greatest creation—the human form. Even after evoking the Biblical phrase that “to the pure of heart all things are pure,” Etty’s explanations fell on deaf ears.

The Powers That Be

We finally arrived in Dallas yesterday. Let me tell you that first of all, it’s a long drive from Alabama to Dallas, even when it’s split into two days. Once in Dallas, we checked into our hotel, which was far nicer than we expected, then we headed to the Dallas Museum of Art. The DMA has live jazz every Thursday and is open until 9 pm.

Saxophonist and composer Ron Jones led an ensemble of players performing his original compositions and other arrangements of jazz standards. So along with seeing the amazing exhibits at the DMA, we were able to enjoy live music as we walked through the museum.

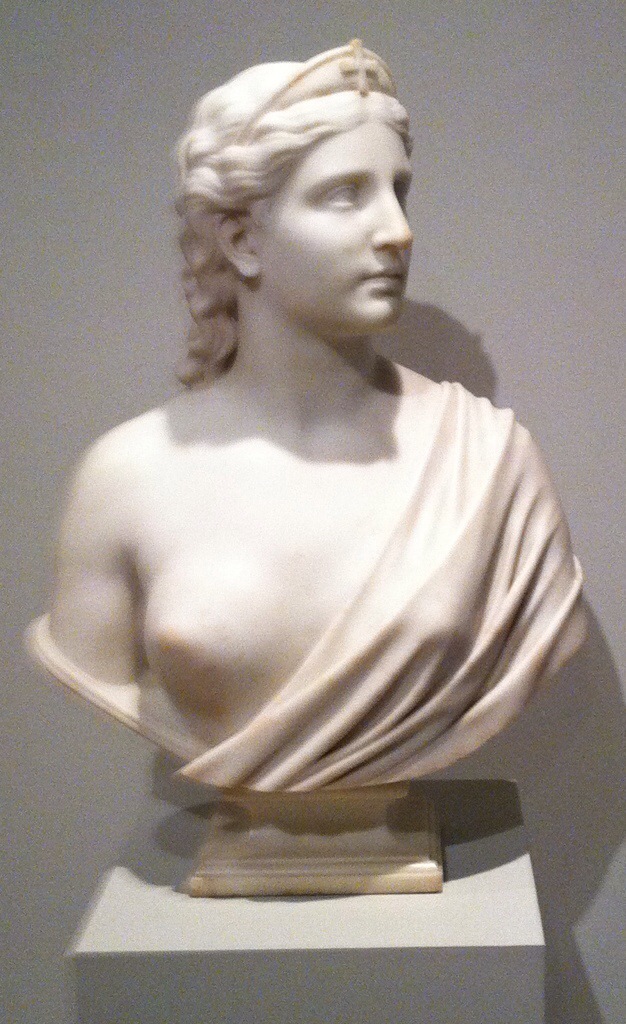

The highlight if my visit to the DMA was seeing the two busts sculptured by Hiram Powers. Powers is a subject of research for me, and I made a pilgrimage to his grave in Florence, Italy, while conducting research at the small English Cemetery of Florence and it’s library.

Hiram Powers epitomized the mid-nineteenth century American artist who, possessing extraordinary technical skill, worked in the predominant neoclassical style. Aided by a wealthy patron, Powers was sent to Washington, D.C. where he sculpted portraits of many government officials, including John Marshall, Daniel Webster, and Andrew Jackson. Later he moved to Italy, where he settled in Florence and established a studio with the assistance of another American sculptor, Horatio Greenough.

Powers’ two most famous sculptures age Greek Slave and Fisher Boy. He produced numerous busts in his lifetime, two of which are on display at the DMA: Faith and America.

Powers’ talent for reproducing a likeness led to a straightforward naturalism that was to remain the basis of his style. Although he later turned to more “idealized” or allegorical works such as “Faith,” “America,” and “Eve Disconsolate,” Powers’ naturalistic approach to his subject matter was perfectly suited to the aesthetic of the time.

The bust, “Eve Disconsolate,” has an interesting story to it. All but maybe four busts by Hiram Powers have a known home such as “Faith” and “America” at the DMA. However, “Eve” had been lost for about 100 years. No one knew where her bust had gone. In 1998, the City of Birmingham, Alabama began to renovate the Alabama Theater located downtown. In the process of restoring the grand theater to its former glory, they were cleaning the bust of the “Lady of the Theater” as she was called. When someone looked at the back of the bust they realized that carved into the back was “H POWERS” and someone recognized the name. It was then that they realized this was “Eve Disconsolate,” one of the missing busts of Hiram Powers. They chose to move the bust from the Alabama Theater where it had been largely neglected since the 1930s to the Birmingham Museum of Art where it resides today.

“I see art as the vehicle of nature and the artist as the collector of nature’s truths and beauties.” Hiram Powers, 1850, in Richard P. Wunder, Hiram Powers.

Artists

I have come to believe that a great teacher is a great artist and that there are as few as there are any other great artists. Teaching might even be the greatest of the arts since the medium is the human mind and spirit.

John Steinbeck

Was Norman Rockwell Gay?

Without thinking too much about it in specific terms, I was showing the America I knew and observed to others who might not have noticed.

—Norman Rockwell

Born in New York City in 1894, Norman Rockwell always wanted to be an artist. Rockwell found success early. He painted his first commission of four Christmas cards before his sixteenth birthday. While still in his teens, he was hired as art director of Boys’ Life, the official publication of the Boy Scouts of America, and began a successful freelance career illustrating a variety of young people’s publications.

At age 21, Rockwell’s family moved to New Rochelle, New York, where Rockwell set up a studio with the cartoonist Clyde Forsythe and produced work for such magazines as Life, Literary Digest, and Country Gentleman. In 1916, the 22-year-old Rockwell painted his first cover for The Saturday Evening Post, the magazine considered by Rockwell to be the “greatest show window in America.” Over the next 47 years, another 321 Rockwell covers would appear on the cover of the Post. Also in 1916, Rockwell married Irene O’Connor; they divorced in 1930.

The 1930s and 1940s are generally considered to be the most fruitful decades of Rockwell’s career. In 1930 he married Mary Barstow, a schoolteacher, and the couple had three sons, Jarvis, Thomas, and Peter. The family moved to Arlington, Vermont, in 1939, and Rockwell’s work began to reflect small-town American life.

In 1943, inspired by President Franklin Roosevelt’s address to Congress, Rockwell painted the Four Freedoms paintings. They were reproduced in four consecutive issues of The Saturday Evening Post with essays by contemporary writers. Rockwell’s interpretations of Freedom of Speech, Freedom to Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear proved to be enormously popular. The works toured the United States in an exhibition that was jointly sponsored by the Post and the U.S. Treasury Department and, through the sale of war bonds, raised more than $130 million for the war effort.

Although the Four Freedoms series was a great success, 1943 also brought Rockwell an enormous loss. A fire destroyed his Arlington studio as well as numerous paintings and his collection of historical costumes and props.

In 1953, the Rockwell family moved from Arlington, Vermont, to Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Six years later, Mary Barstow Rockwell died unexpectedly. In collaboration with his son Thomas, Rockwell published his autobiography, My Adventures as an Illustrator, in 1960. The Saturday Evening Post carried excerpts from the best-selling book in eight consecutive issues, with Rockwell’s Triple Self-Portrait on the cover of the first.

In 1961, Rockwell married Molly Punderson, a retired teacher. Two years later, he ended his 47-year association with The Saturday Evening Post and began to work for Look magazine. During his 10-year association with Look, Rockwell painted pictures illustrating some of his deepest concerns and interests, including civil rights, America’s war on poverty, and the exploration of space.

So much has been written about Rockwell, including his own autobiography, that his life would seem to be a closed case. But he receives a fascinating rethinking in Deborah Solomon’s American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell, in which she makes a case for his homoerotic desires.

Although she can’t conclusively prove that Rockwell had sex with men, she makes an argument that he “demonstrated an intense need for emotional and physical closeness with men” and that his unhappy marriages were attempts at “passing” and “controlling his homoerotic desires.” Rockwell also had a close bond with the openly gay artist J.C. Leyendecker and his gay brother, Frank, also an artist, and counted himself as the “one true friend” the brothers had. As Solomon states, “it was both an artistic apprenticeship and an unclassifiable romantic crush.” According to Solomon, Rockwell went on to have close relationships with his studio assistants (even sleeping in the same bed with one on an extended camping trip) and created his own version of idealized boyhood beauty.

While digging into his back story, Solomon offers sensitive close readings of some of his well-known works that smack of homoeroticism but have been cherished (and sanitized) for their depiction of all-American values. For example, when she points out that in the beloved portrait of a young boy seated next to a police officer at a diner counter, “The Runaway,” the cop can be seen as a “figure of tantalizing masculinity, a muscle man in a skin-tight uniform and boots,” it’s almost as if we’re seeing a proto-Tom of Finland emerge before our eyes. In this analysis, it’s not only a painting that represents a desire for both independence and security, it shows the tenderness between men (of any age) and encapsulates the complicated life and desires of an artist many have written off as a proselytizer of an American dream that didn’t include them. According to Solomon, Rockwell was constantly yearning for another ideal, of youthful male beauty, that always seemed to lie beyond reach.

I’m all for taking a close look into history and uncovering evidence that a historical figure may have been gay; however, this is one instance where I tend to think that Solomon is making a bit of a stretch. I personally have never viewed Norman Rockwell’s work as homoerotic, but as idealistic Americana. I certainly see no traces of a Tom of Finland police officer in the doughy 1950s officer of “The Runaway.” I will admit that I have not read Deborah Solomon’s book nor have I had the chance to evaluate the evidence, but it seems like pure speculation to me. American Mirror has produced a fair amount of controversy, so I do not think I am alone in finding fault with Solomon’s assumptions.

Patrick Toner, a professor at Wake Forest University, wrote:

In her new biography, however, Deborah Solomon presents a Rockwell we might not be inclined to love so much. Her most shocking claim is that he was sexually attracted to young boys. Almost equally shocking, but more subtle, is her suggestion that Rockwell’s self-absorption had a body count—his behavior led directly or indirectly to at least three ugly deaths.

There is no reason to go along with Solomon about these things. As I’ll show, her arguments—such as they are—are deeply flawed, and she has a pronounced tendency to either distort or ignore evidence to the contrary of her claims. As her interpretation of Rockwell himself is irremediably flawed, so is her interpretation of his art. Hers is a book without merit.

Toner continues by stating:

Her evidence for Rockwell’s pedophilia consists of three intertwined claims: First, he paints a lot of boys. Second, he forms strong relationships with some of the boys who serve as models for these paintings. Third, some of these paintings are sexually suggestive. Solomon thinks that pedophilia serves as the best unifying explanation for these claims. I doubt even that, but even if it were the case, there are problems with all three.

Toner’s review of American Mirror is quite long but interesting. From what I have read, it seems as if Solomon had a particular agenda, probably for publicity, in writing her Rockwell biography. It seems that sensationalism is what sells biographies these days, and Solomon has certainly written what seems to be a sensational book. The fact is, if Norman Rockwell was homosexual, there seems no way of proving it except through speculation. I doubt it would surprise many people if one of America’s greatest artists was gay, because let’s face it, most of history’s great artists were. However, I think Rockwell would have probably painted a new version of the picture below to answer the questions of his sexuality:

In “The Gossips,” a Saturday Evening Post cover from March 6, 1948, it seems Rockwell had a neighbor who started a disagreeable rumor about him. What can one do about a nasty gossip? Well, if you are a famous illustrator, you can paint a cover about it. It started with just a couple of people, then it just grew, leaving Rockwell in need of more models. The result, said the editors, is that we see “almost the entire adult population of Arlington, Vermont.” As he worked on the project, the artist worried that his friends and neighbors might be offended, so he included his wife and himself. Mary Rockwell is second and third in the third row, spreading the rumor via rotary phone. In the gray felt hat in the bottom row is, of course, the artist himself (you can click on the image for a close-up). You’ll notice the lady at the end is the one at the beginning who started the rumor, and our friend Rockwell appears to be giving her a piece of his mind. Apparently, the neighbor who started the rumor in real life never spoke to Rockwell again. I have a feeling it was no great loss.