Monthly Archives: September 2025

Art,

Art,

By Herman Melville

In placid hours well-pleased we dream

Of many a brave unbodied scheme.

But form to lend, pulsed life create,

What unlike things must meet and mate:

A flame to melt—a wind to freeze;

Sad patience—joyous energies;

Humility—yet pride and scorn;

Instinct and study; love and hate;

Audacity—reverence. These must mate,

And fuse with Jacob’s mystic heart,

To wrestle with the angel—Art.

About the Poem

Herman Melville’s short but powerful poem Art distills into a few compact lines the contradictory forces at the heart of creation. It opens with a scene of calm:

“In placid hours well-pleased we dream

Of many a brave unbodied scheme.”

Here, Melville acknowledges what many of us know too well—ideas come easily in quiet moments. Our minds are full of “unbodied schemes,” bold plans and visions that exist only in imagination. But dreaming alone is not art. The difficulty lies in giving those dreams form, in pulling them out of the ether and shaping them into something tangible.

Melville describes this process as a marriage of opposites:

“A flame to melt—a wind to freeze; Sad patience—joyous energies; Humility—yet pride and scorn; Instinct and study; love and hate; Audacity—reverence.”

Each pair of opposites illustrates the tension of creation. Art requires both the fire of inspiration and the cooling restraint of discipline. It requires patience to endure long labor, and bursts of joy to keep the work alive. An artist must balance humility before the task with pride in their own vision, instinct with study, raw emotion with critical judgment.

These contradictions are not obstacles—they are the materials. To create something of value, the artist must bring them together, “fuse with Jacob’s mystic heart, / To wrestle with the angel—Art.”

That final biblical allusion is striking. In Genesis, Jacob wrestles through the night with an angel, demanding a blessing and emerging wounded but transformed. Melville suggests that to make art is a similar struggle: a contest with forces larger than oneself, leaving the artist changed, exhausted, and blessed with creation.

For Melville—better known for his sprawling novels like Moby-Dick—this poem is a confession of the artist’s burden. Creation is not a smooth act but a wrestling match, a fusion of contradictions, a labor of both agony and ecstasy.

I find this poem resonates deeply with the creative process in any form—whether writing, painting, composing, or even living an honest life. We all carry “brave unbodied schemes,” but only by engaging in the struggle, by wrestling with the angel, do we bring them into the world.

About the Poet

Herman Melville (1819–1891) is best remembered today as the author of Moby-Dick (1851), one of the towering works of American literature. Yet his career was far from smooth. His early sea novels brought him popularity, but his later, more ambitious works—Moby-Dick included—were commercial failures in his lifetime. Melville turned to poetry in his later years, publishing several volumes, including Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War (1866) and Timoleon (1891). His poetry often reveals the same themes as his prose: the struggle of humanity against vast forces, whether nature, fate, or, as in this poem, the act of creation itself.

Turning the Page on September

It’s Monday again—the start of another week. Hard to believe we’re already at the end of September and about to turn the calendar over to October. Here in Vermont, the seasons are shifting quickly, but with the drought this year, the leaves have already reached their peak. Before long, the trees will be bare, and autumn will give way to the starkness of early winter.

Today will be a busy one for me. I have tours scheduled through much of the day, including one I’ll be giving for some visiting family from Alabama. Later on, I’ll also be leading a special tour for a class, which should be a nice change of pace. Beyond that, it looks like a fairly regular week ahead—but of course, saying that and it actually being so are two very different things. Life has a way of throwing in surprises just when we least expect them.

As the last days of September slip away, I’m reminded of how quickly the seasons turn. One moment the trees are aflame with color, and the next, their branches are bare against the sky. Time seems to move the same way—quietly, steadily, and all too fast. Here’s to making the most of these fleeting days as we step into October. I’ll do my best to take this week as it comes, and I hope each of you has a good week ahead as well.

Train Up a Child

“Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old he will not depart from it.”

— Proverbs 22:6

When I look back on my upbringing, I can see how deeply this verse shaped me. My parents raised me to be good, moral, and honest. They taught me to love my neighbor and to respect those who deserved respect. They weren’t always strong on Galatians 3:28—“There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” They believed, as many of us are taught, that we were somehow better than others. Yet they never taught me hate. On my own, I came to embrace Galatians 3:28 fully, and in doing so I saw how God’s love is meant to break down every wall we build between ourselves.

They did, however, instill in me the message of 1 Corinthians 13:13: “And now these three remain: faith, hope, and love. But the greatest of these is love.” That teaching runs like a thread through my life and faith.

It saddens me now to see them support political leaders who represent the opposite of everything they once taught me. I have told them this many times, but it only makes them angry. Since I came out, they have become increasingly conservative, moving further away from the love and compassion they once instilled in me.

Yet in the paradox of that pain, I have found myself drawn deeper into faith. I cling to Psalm 143:10: “Teach me to do your will, for you are my God; may your good Spirit lead me on level ground.” When those I love seem to turn against what they once believed, I turn back to God, asking Him to steady my steps and to keep me walking in love. And I remember Colossians 1:28: “He is the one we proclaim, admonishing and teaching everyone with all wisdom, so that we may present everyone fully mature in Christ.”

The Bible clearly teaches us equality, but it also reminds us that equality in Christ does not mean we won’t be separated on Judgment Day. In Matthew 25:31–46, sometimes called the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats or “The Son of Man Will Judge the Nations,” Jesus tells us that when He returns, He will divide the righteous from the unrighteous—those who lived out His commands from those who did not. Just before this, in the Parable of the Talents (Matthew 25:14–30), the master praises the faithful servants who used what they were given wisely, saying, “Well done, good and faithful servant.” That is what I hope to hear on Judgment Day.

Matthew 25:31–46 shows us what a righteous nation looks like: one that feeds the hungry, welcomes the stranger, clothes the naked, cares for the sick, and visits the imprisoned. It also shows us what a wicked nation looks like: one that ignores the needs of the most vulnerable. Tragically, the United States today more closely resembles the wicked nation than the righteous one. Jesus’s words in Matthew 25:40 are a clear warning: “And the King will answer and say to them, ‘Assuredly, I say to you, inasmuch as you did it to one of the least of these My brethren, you did it to Me.’”

My parents raised me to value honesty, respect, and love, and though they may have drifted from those lessons, I still hold to them. Scripture affirms that love is the greatest calling, that equality is God’s design, and that true righteousness is measured by how we treat “the least of these.” Nations and people alike will be judged by this standard. I choose to live the faith I was taught at its best, praying that my life reflects Christ’s command to love, so that in the end I might hear, “Well done, good and faithful servant.”

Timeless Fragments: The Male Torso in Art

You can go on Etsy.com and search “male torso” and you’ll come up with hundreds, if not thousands, of works of the male torso. Sculptures, paintings, photographs, and even decorative candles in the shape of a chest all testify to the enduring fascination with this particular part of the human form. The torso has long been a central subject in art because it distills the human body to its essence: strength, sensuality, vulnerability, and ideal proportion. Artists across time and cultures have used the male torso not only to study anatomy but also to express ideals of beauty, divinity, and desire.

Ancient Beginnings

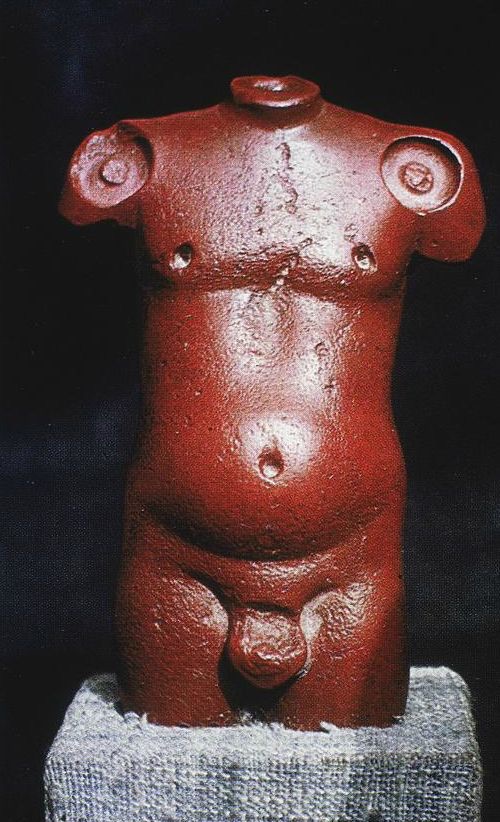

One of the oldest surviving examples is the Red Jasper Torso from Harappa, an Indus Valley civilization sculpture dating back over 4,000 years. Despite its small size, it displays a careful attention to musculature and balance. A similar focus on proportion appears in the Male Torso from Mora, Mathura (2nd century CE), which reflects the Indian tradition of combining sensual form with spiritual resonance. Even in antiquity, the torso stood as a shorthand for the power and beauty of the whole body.

The Classical Legacy

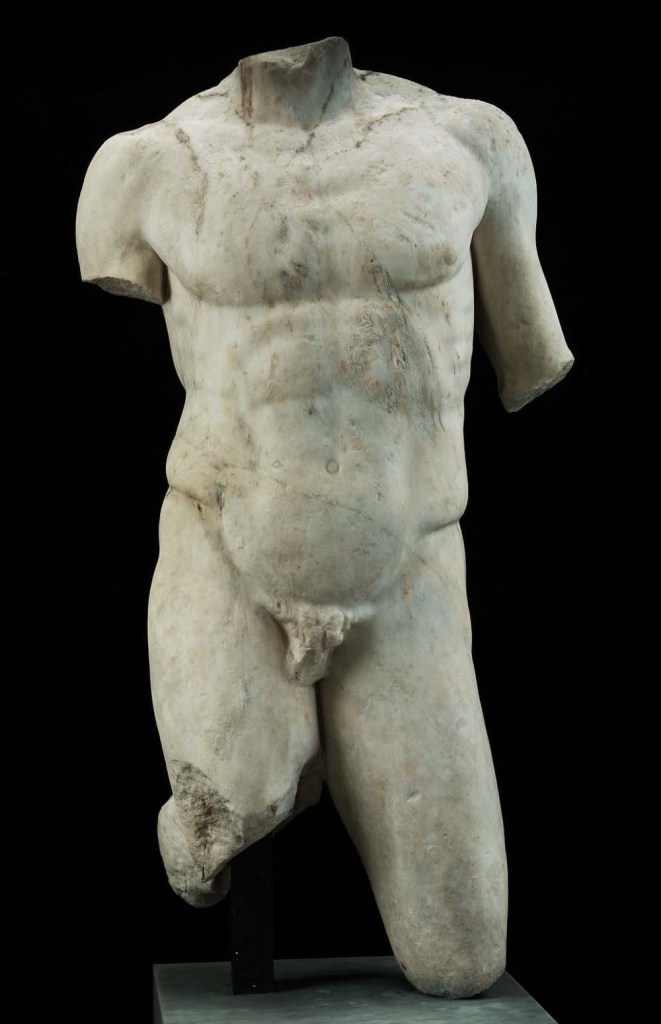

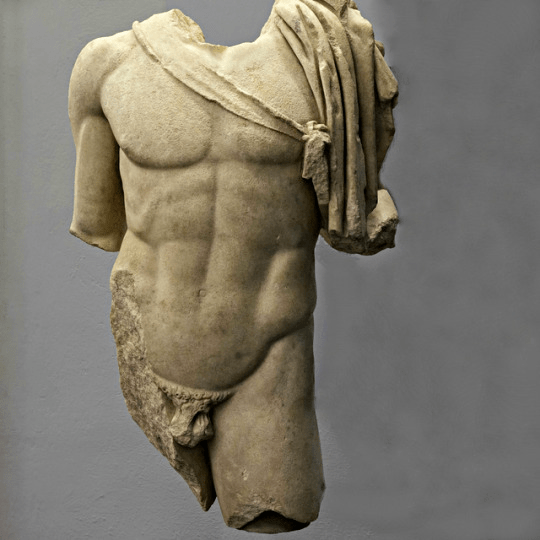

The Greco-Roman world perfected the torso as an independent art object. A striking example is the Male torso (Mercury?) in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, or the Roman Marble Male Torso (1st century BCE–1st century CE) once auctioned at Christie’s. Both works emphasize muscular structure and the heroic stance, capturing divine strength in a fragment. Most famous of all is the Belvedere Torso (Vatican Museums), a mutilated but monumental fragment that became a touchstone for Renaissance artists. Michelangelo studied it obsessively, and its twisting form influenced the dynamic poses of his Sistine Chapel figures.

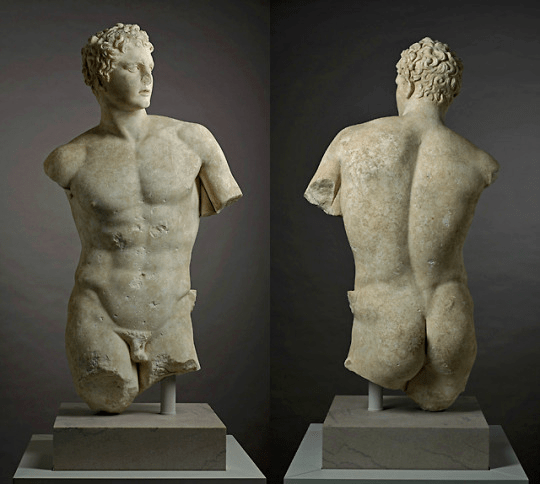

Other classical examples show how the torso could embody narrative as well as anatomy. The Statue of Meleager (Harvard Art Museums) presents the hunter hero in a poised yet relaxed stance, the carefully modeled chest and abdomen conveying both strength and elegance. The Fragmentary statue of Diomedes from the Great Baths of Aquileia (National Archaeological Museum of Aquileia) reduces the heroic figure to its torso, yet the carving retains a sense of vitality and forward motion, reminding viewers of the power and drama embodied in the classical male form.

From Study to Modernism

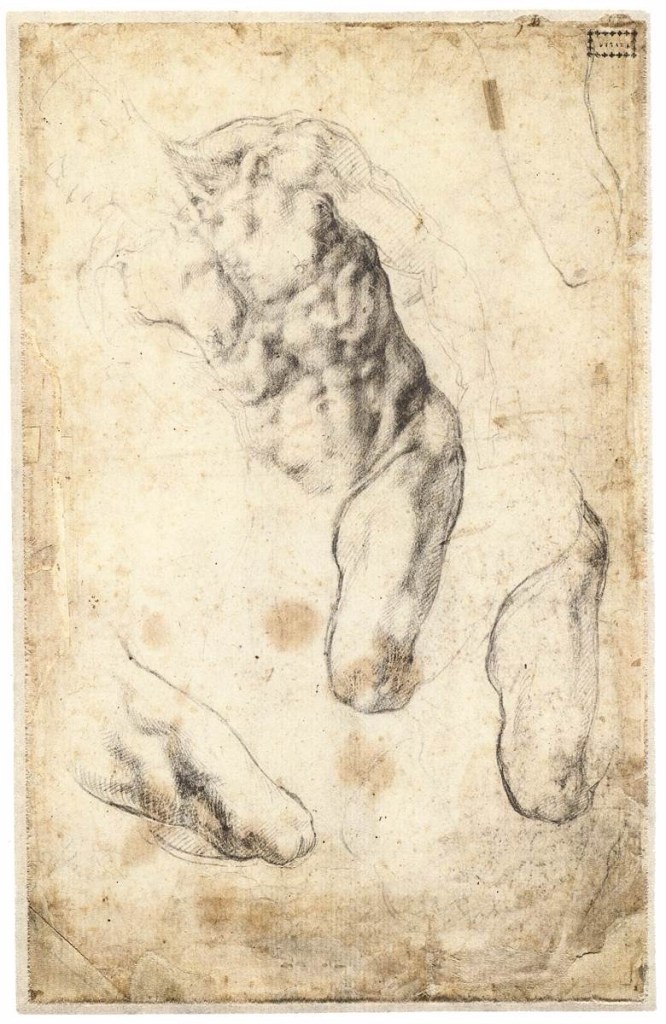

Renaissance and Neoclassical artists often drew the torso as a central exercise in mastering anatomy. Michelangelo’s Studies of a Male Torso and Left Leg (1519–21, Teylers Museum) demonstrate his fascination with musculature and motion, while Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Academic Study of a Male Torso (1801, National Museum, Warsaw) shows the continuation of this tradition into the academies of Europe. By the 20th century, Constantin Brancusi abstracted the form into pure shape in his Male Torso (1917, Cleveland Museum of Art), reducing muscles and bones to flowing simplicity. Later, Fernando Botero reimagined the body on monumental, exaggerated terms with his Male Torso Statue in Buenos Aires—rotund, playful, and commanding.

Torso in Photography

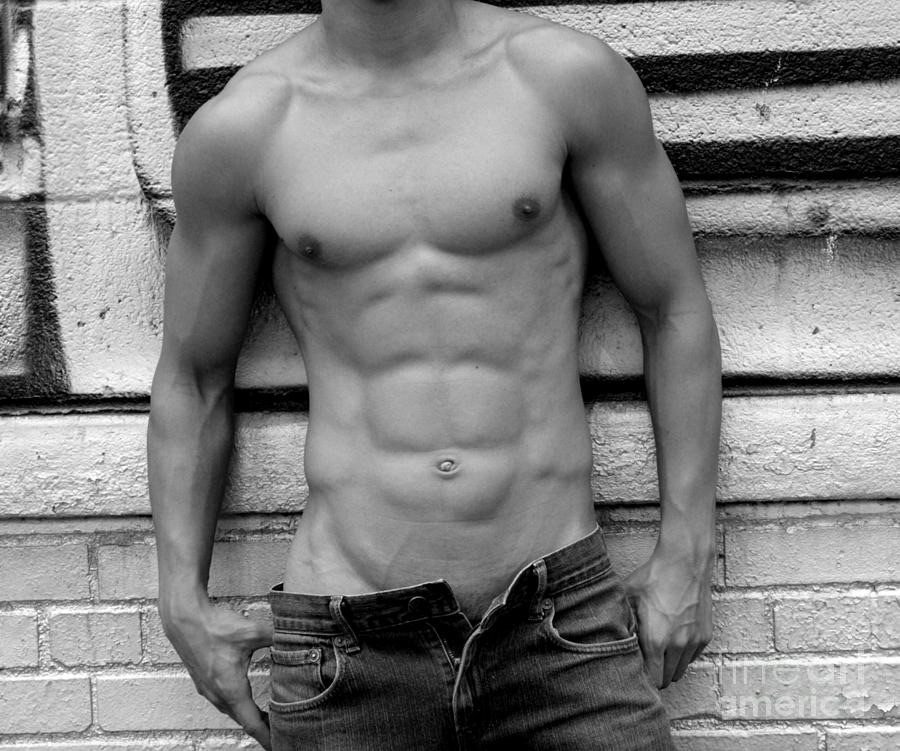

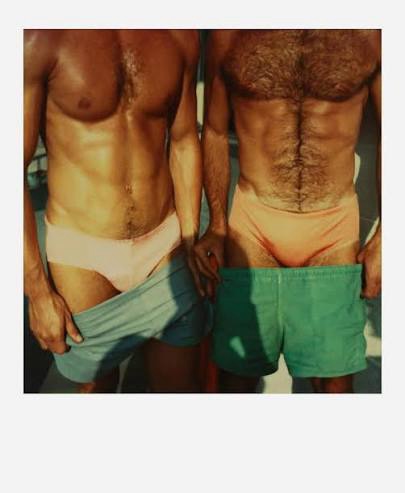

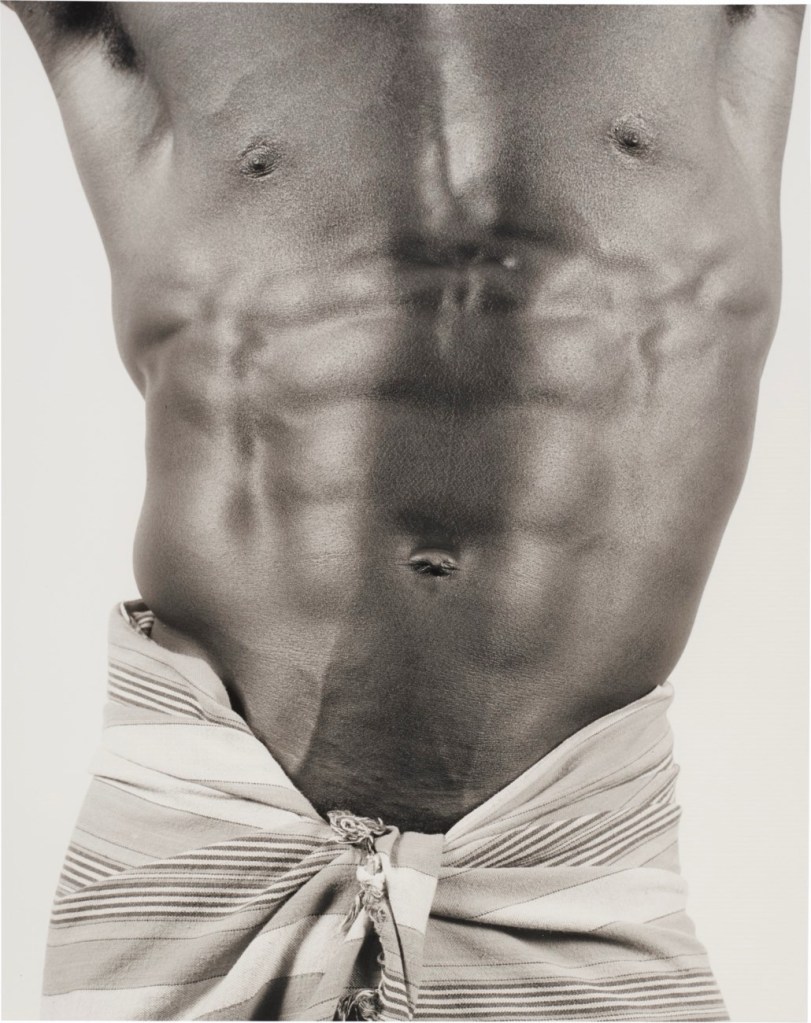

With the advent of photography, the torso remained central to the visual exploration of masculinity. Mark Ashkenazi’s Male Abs turns the torso into an icon of modern fitness culture, a sleek and stylized emblem of desire. In contrast, Tom Bianchi’s Fire Island Pines, Polaroids: 1975–1983 (published 2013) presents torsos in intimate, personal settings. One image in particular, where Bianchi himself appears on the right, captures not just form but community, sensuality, and queer joy. Robert Mapplethorpe’s photograph of Derrick Cross isolates the male torso with sculptural precision, transforming flesh and muscle into a study of form, texture, and shadow that blurs the line between portrait and classical sculpture.

A Universal Fascination

What makes the male torso so timeless? Perhaps it is because the torso is both part and whole. As a fragment, it invites us to imagine what is missing; as a complete subject, it embodies strength, beauty, and vulnerability in one. Sculptors, painters, draftsmen, and photographers alike have returned to it again and again, finding in the lines of shoulders, the arch of ribs, and the rhythm of abdominal muscles a visual poetry that speaks across centuries. Contemporary works such as James Casey Lane’s The Shirt continue this dialogue, blending classical form with modern gesture to remind us that the torso is as much about movement and emotion as it is about anatomy.

From Harappa to Fire Island, the male torso remains an enduring symbol of the human form and its many meanings—divine, erotic, heroic, and profoundly human.