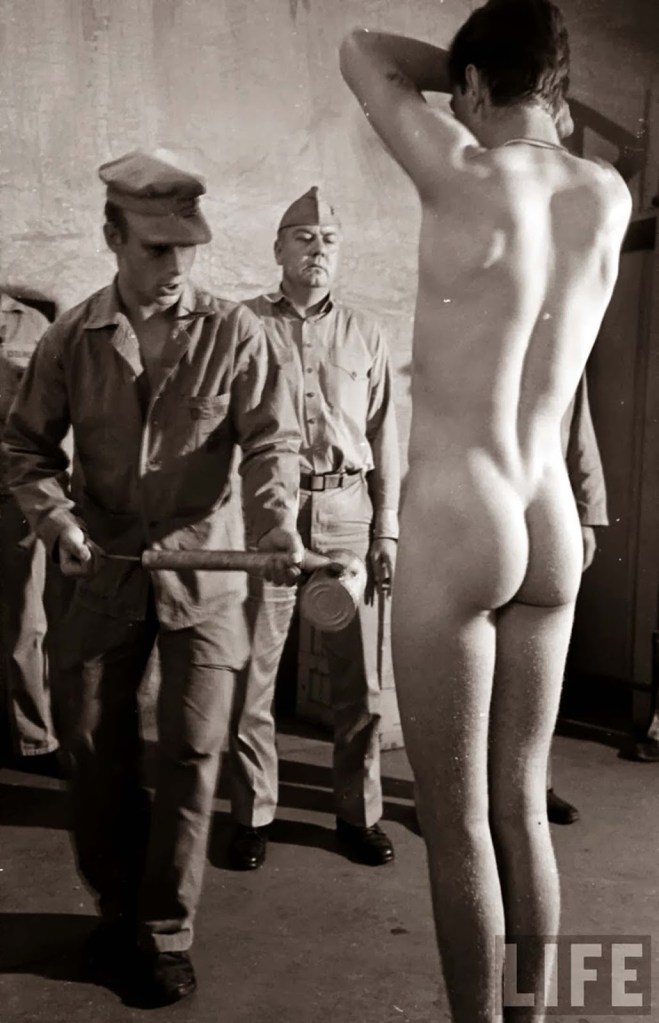

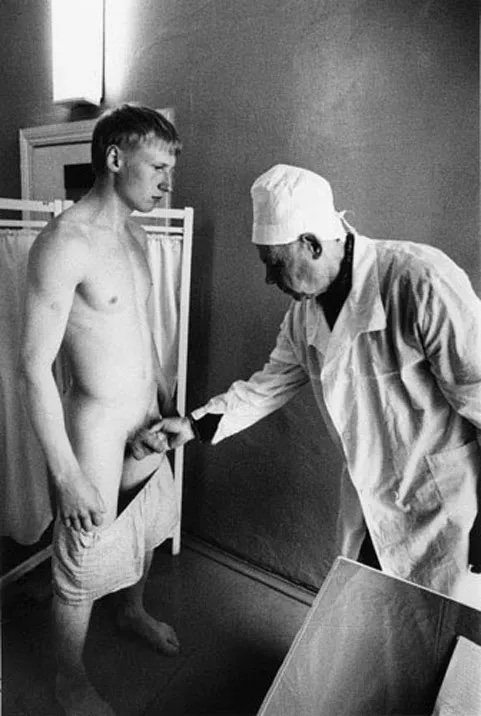

Yesterday, while reading, I came across a reference that stopped me in my tracks: gay men in Toronto rubbing the bare butt on a statue for luck. As both a gay man and a museum person, that kind of detail lights up every curiosity circuit in my brain. The scene also reminded me of the old military practice of the “short arm inspection”—the venereal disease check that required soldiers to line up and present themselves for examination. Little moments of sexualized institutional history like that have always existed in the margins, half whispered but universally known.

And so it seemed fitting that the statue in question was the Alexander Wood monument that once stood in Toronto’s Church and Wellesley Village—a monument rooted in its own scandal of inspection, accusation, and rumor.

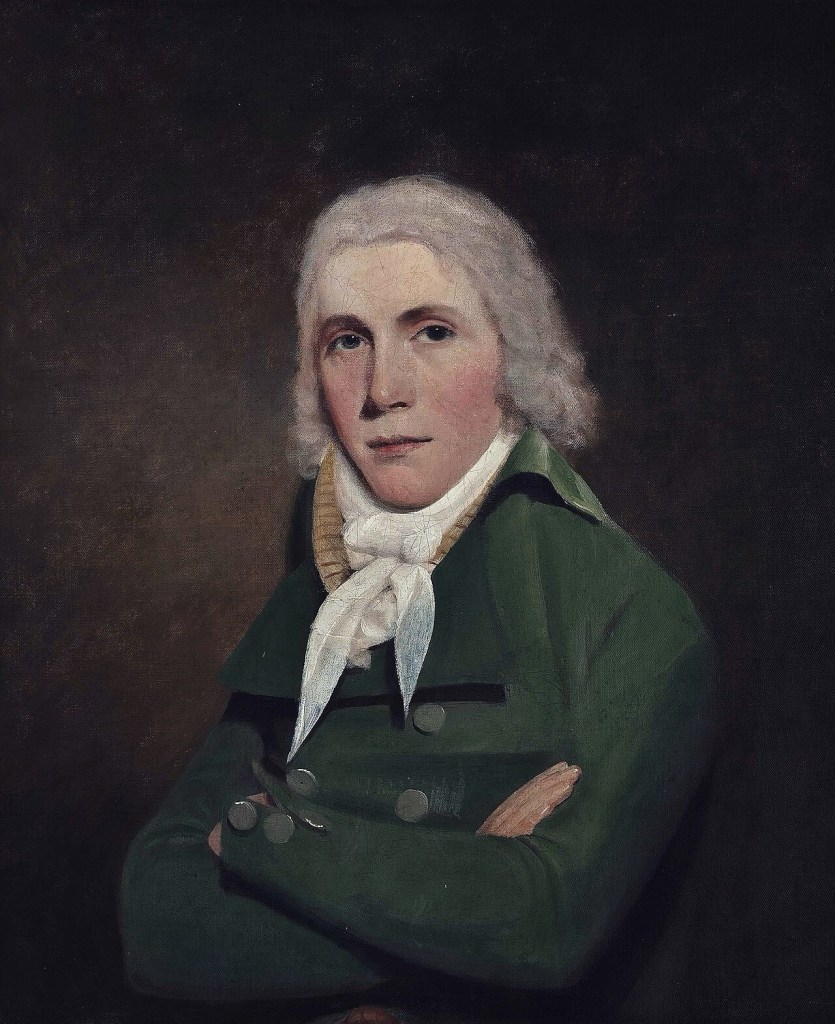

Alexander Wood (1772–1844) was a Scottish merchant and magistrate who became a prominent figure in early Toronto (then York). He served in several civic roles and was involved in shaping the young colony. But today, he’s remembered primarily for a scandal that forever marked his reputation—and later, queer history.

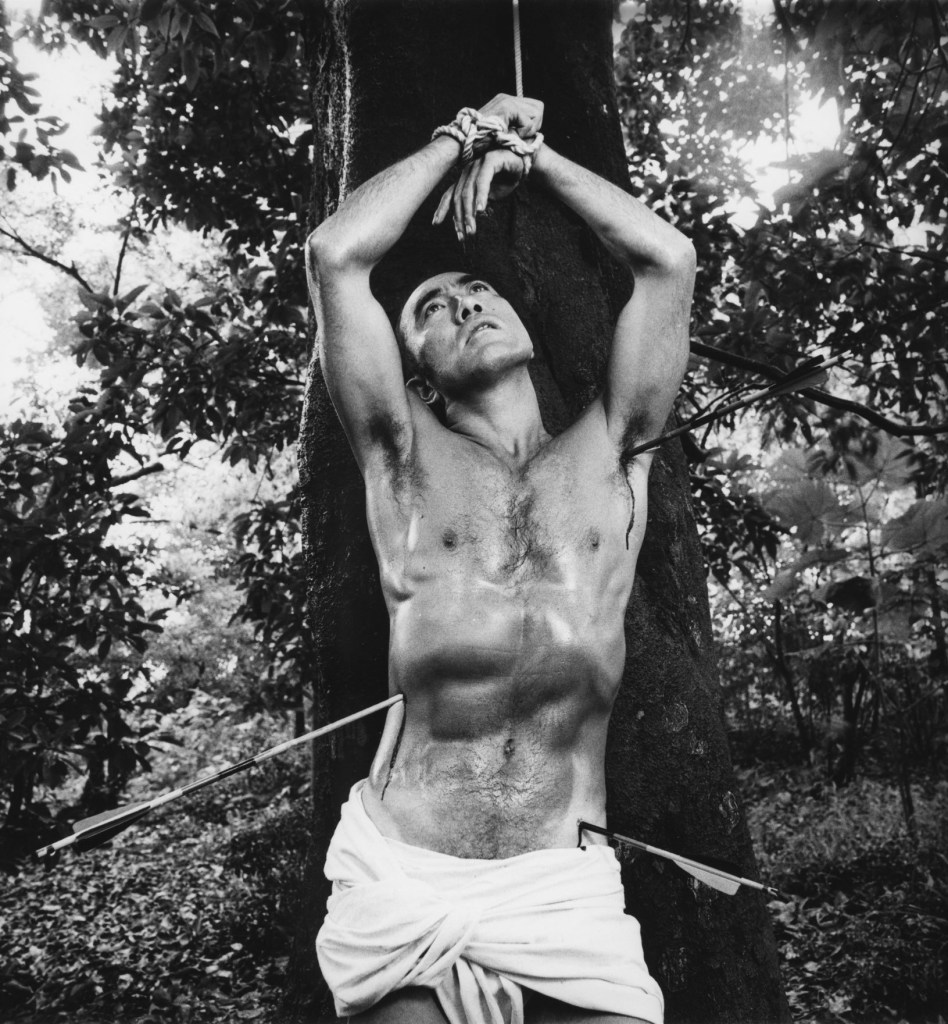

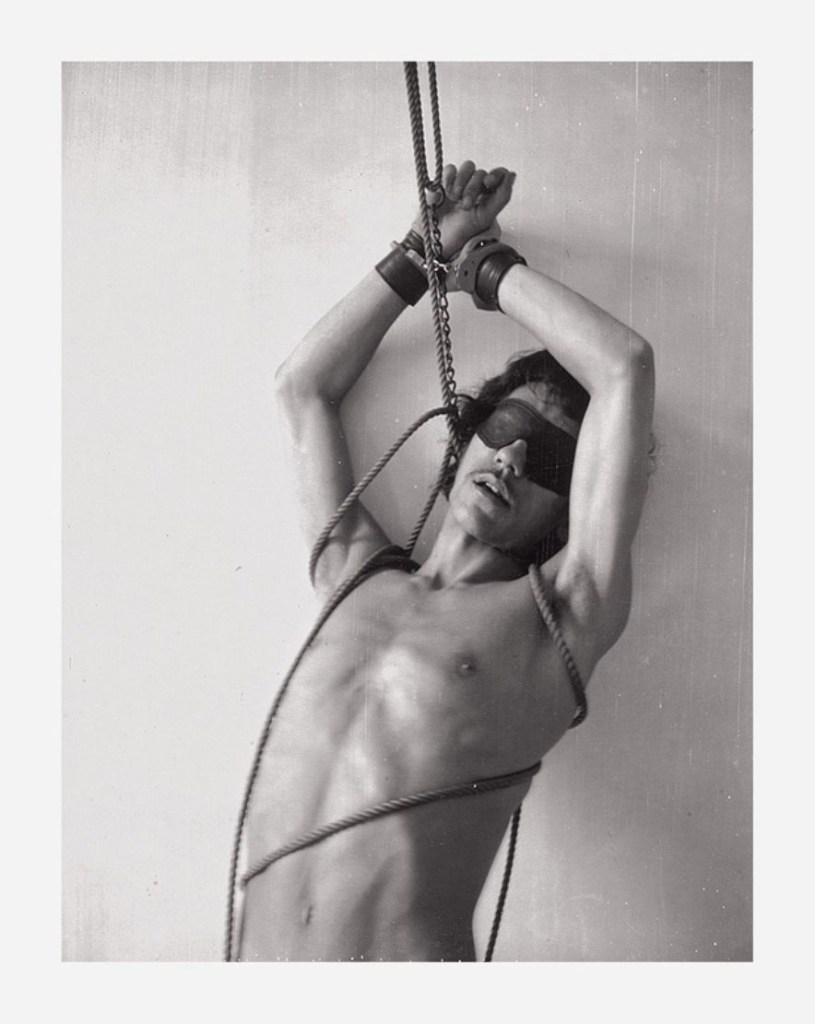

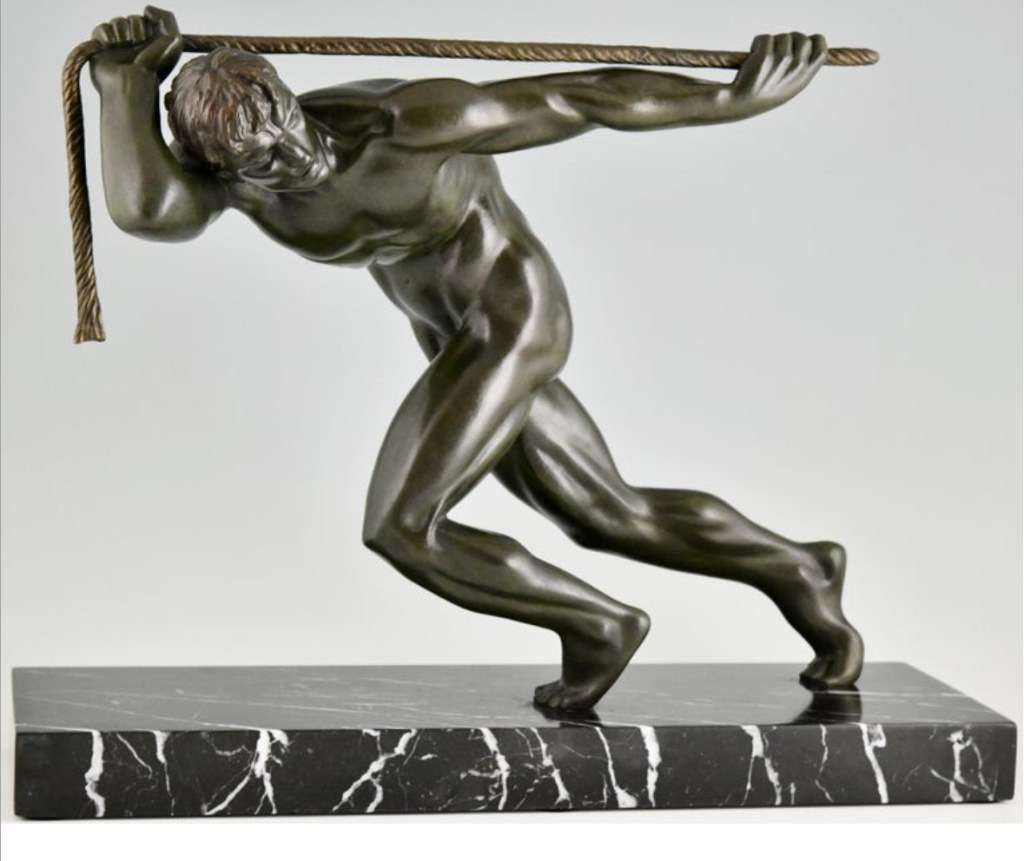

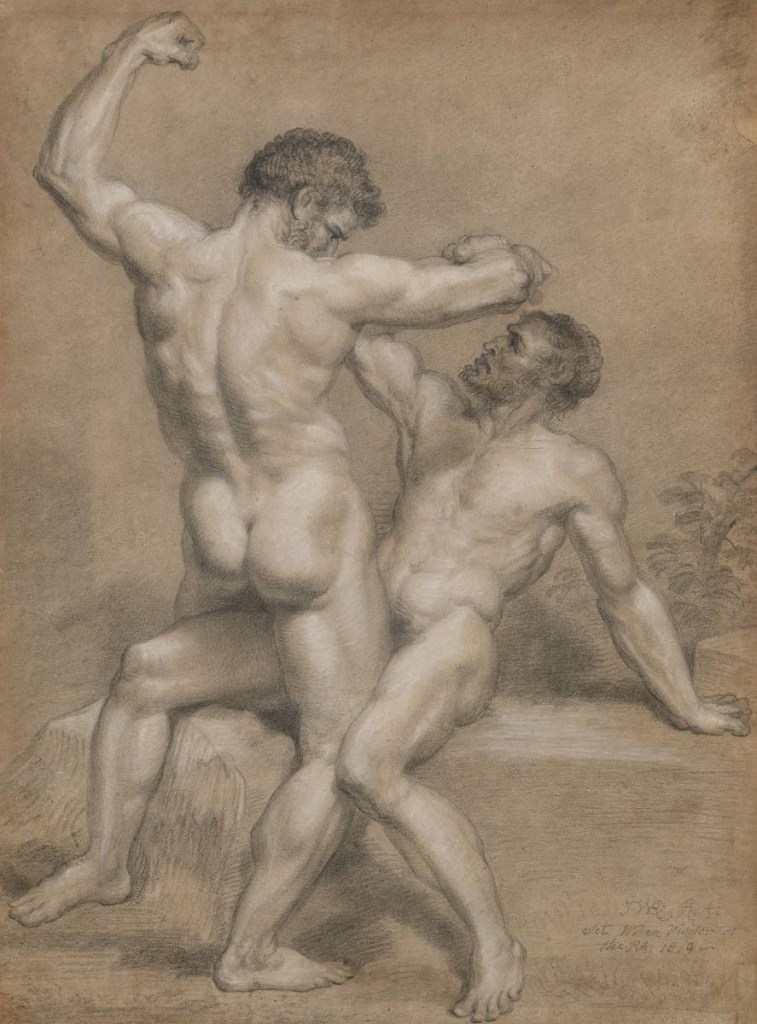

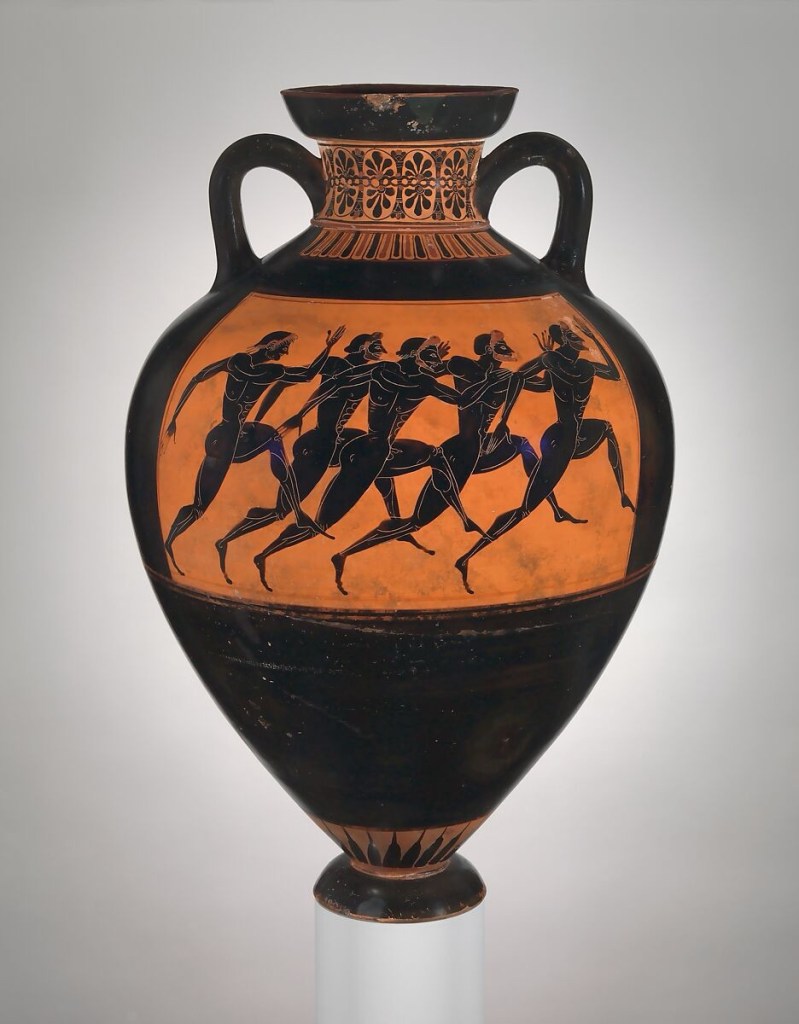

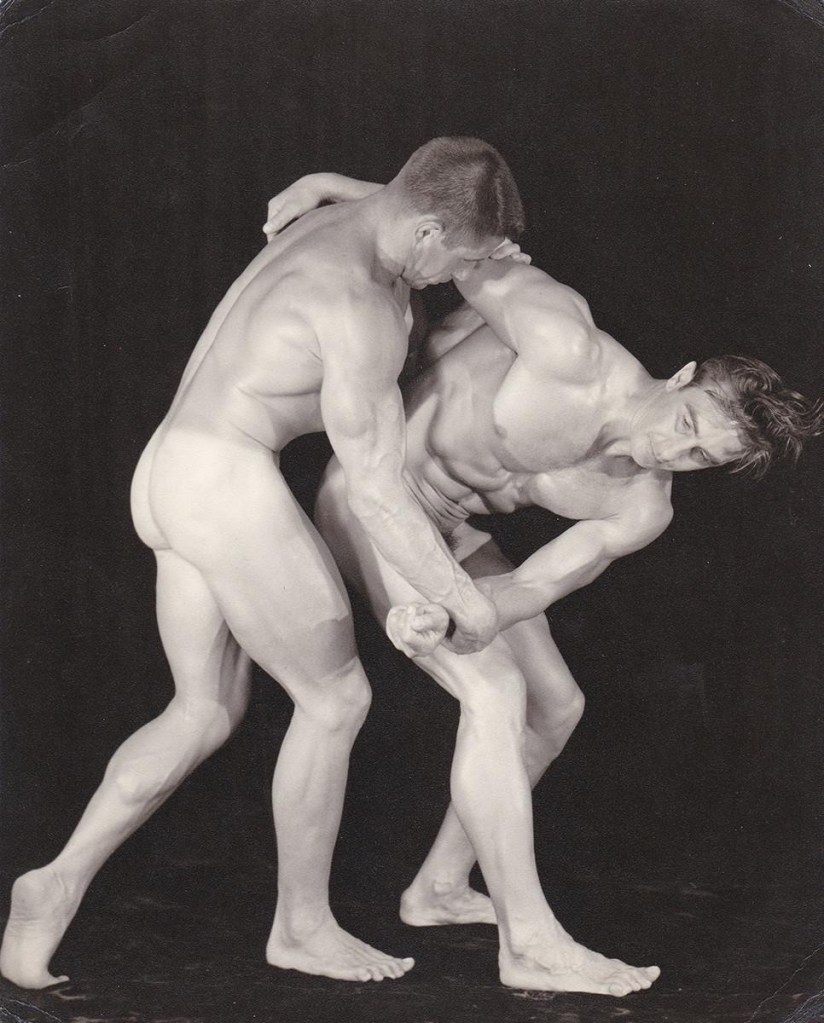

In 1810, a young woman named Miss Bailey claimed she had been sexually assaulted. Her description was vague, but she insisted she could identify the assailant by marks on his genitals.

As a magistrate, Wood investigated the case, questioning several male suspects. Historical accounts state that he personally inspected their genitals to look for corroborating marks.

This highly unusual method sparked gossip and ridicule.

What makes the incident even murkier is that many historians doubt the woman’s existence altogether. Some believe “Magdalena Nagle” may have been invented—either by Wood, his rivals, or the community at large. The absence of solid records fueled speculation in his own time and afterwards.

Regardless, the scandal led to public humiliation and accusations—spoken and unspoken—about Wood’s sexuality. Though never charged with wrongdoing, he fled temporarily to Scotland before quietly returning to his life in Upper Canada.

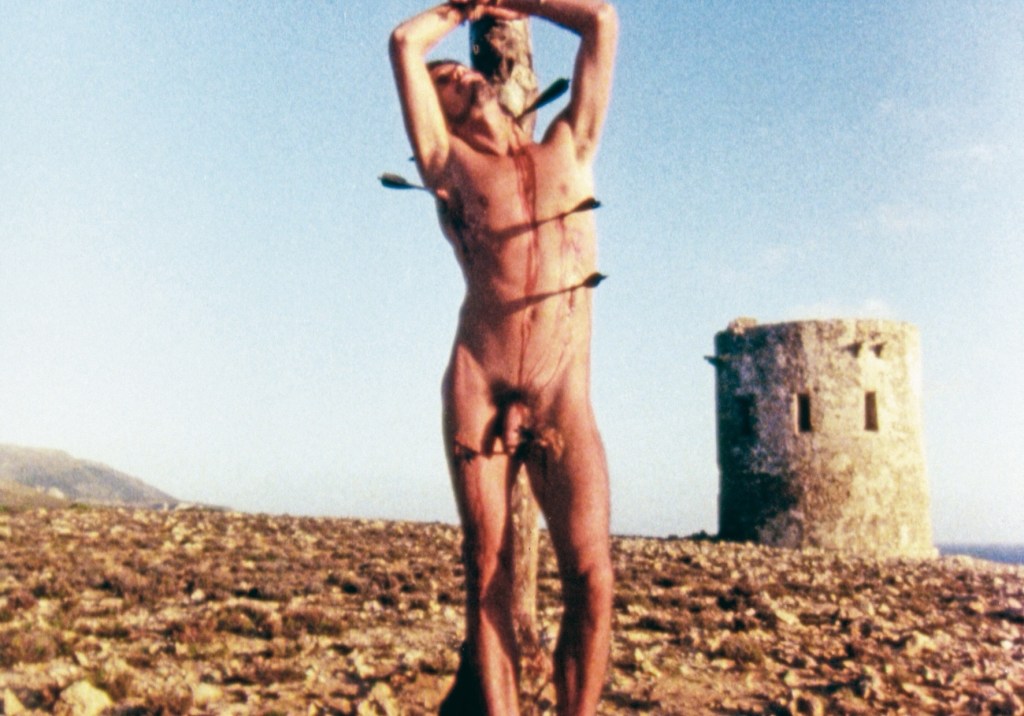

In 2005, Toronto’s LGBTQ+ community sought to commemorate queer history in public space. Although Wood’s sexual orientation is not documented, many queer historians reclaimed him as a possible queer ancestor—a man punished socially for perceived sexual deviance long before there was a vocabulary to defend himself.

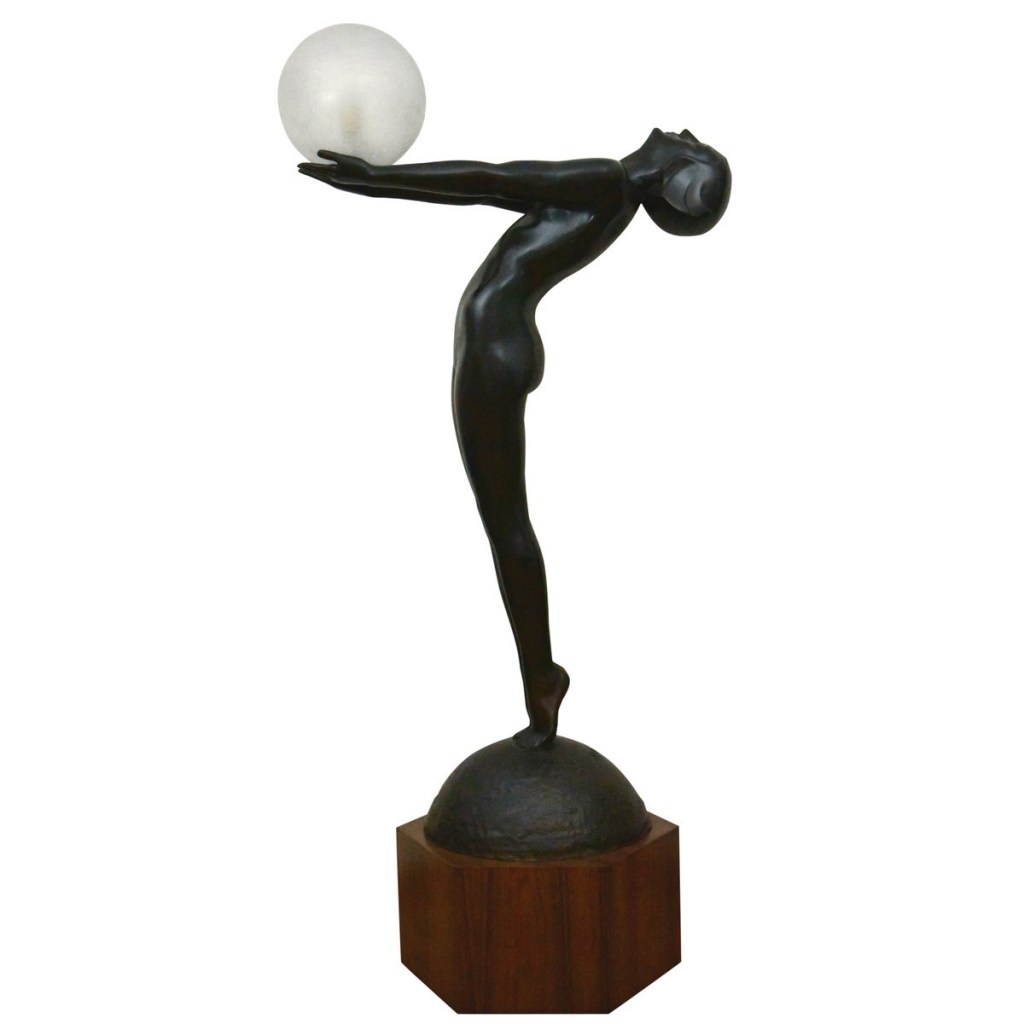

Thus the community commissioned a statue honoring both his life and his place in queer memory.

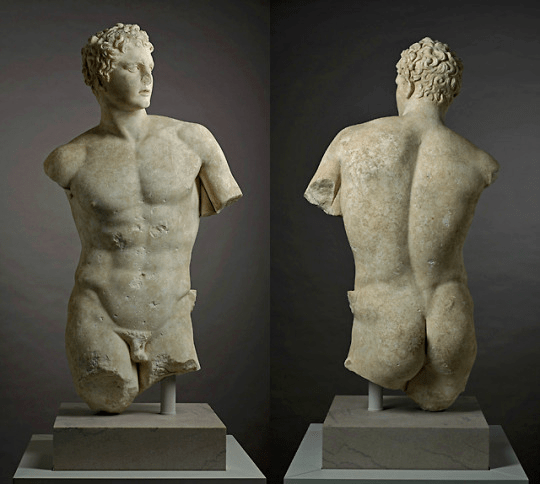

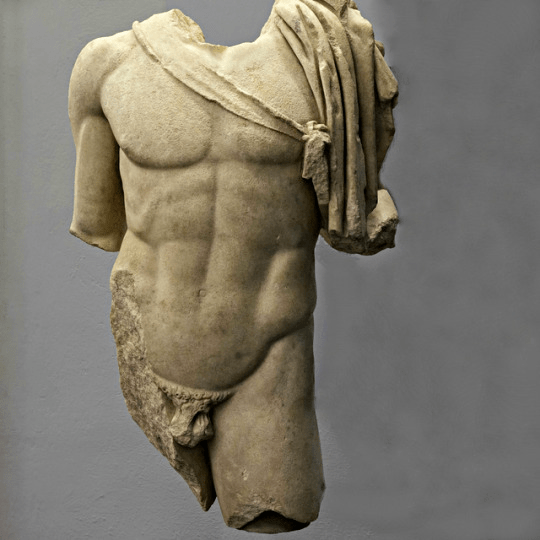

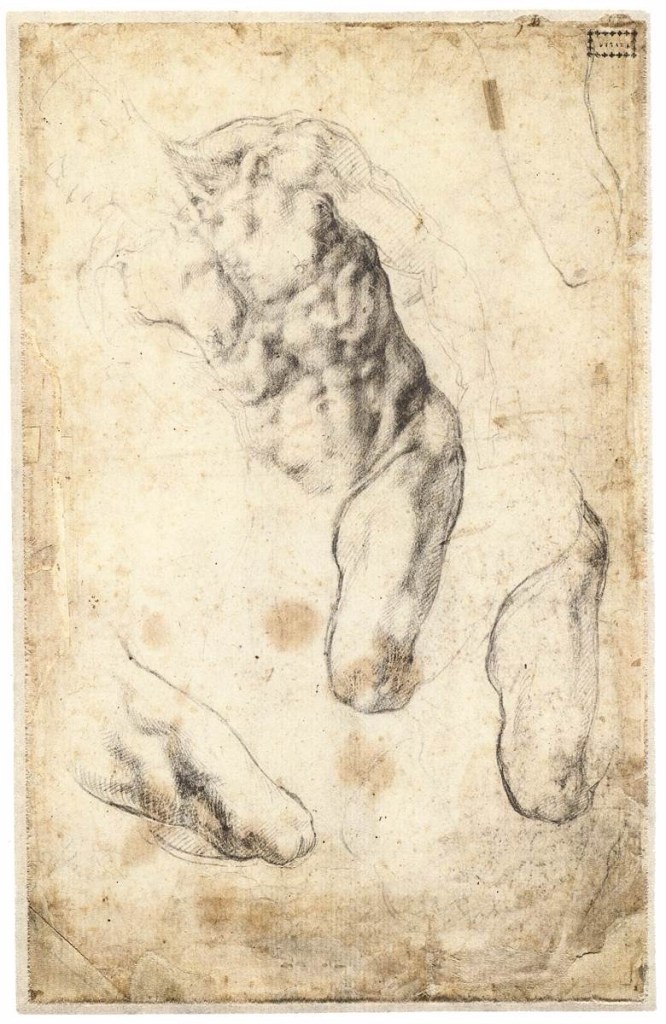

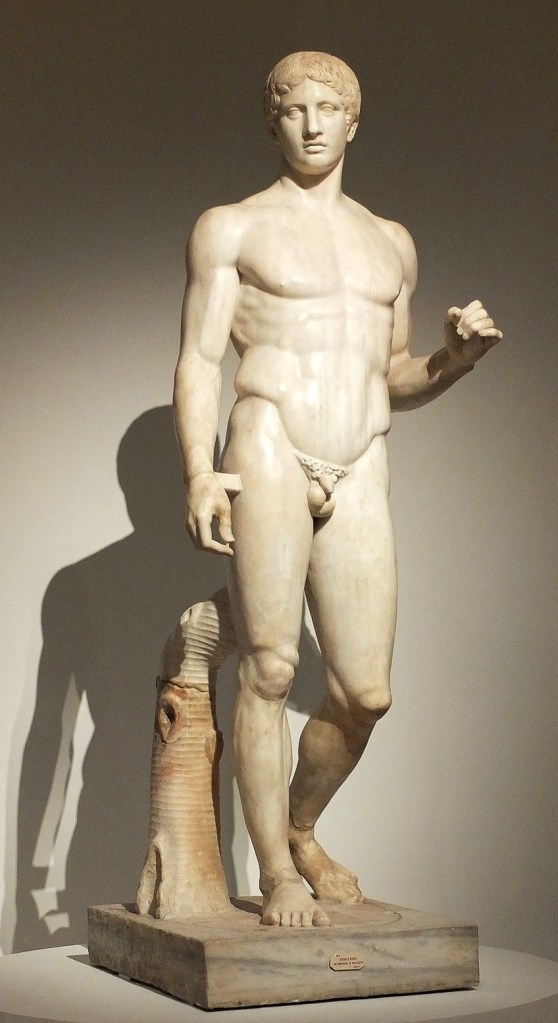

lThe bronze sculpture, created by Del Newbigging, depicted Wood in early-19th-century attire—not a military uniform, but the formal dress of a gentleman of his era. His pose was confident, with one hand tucked behind him and the other holding a walking stick.

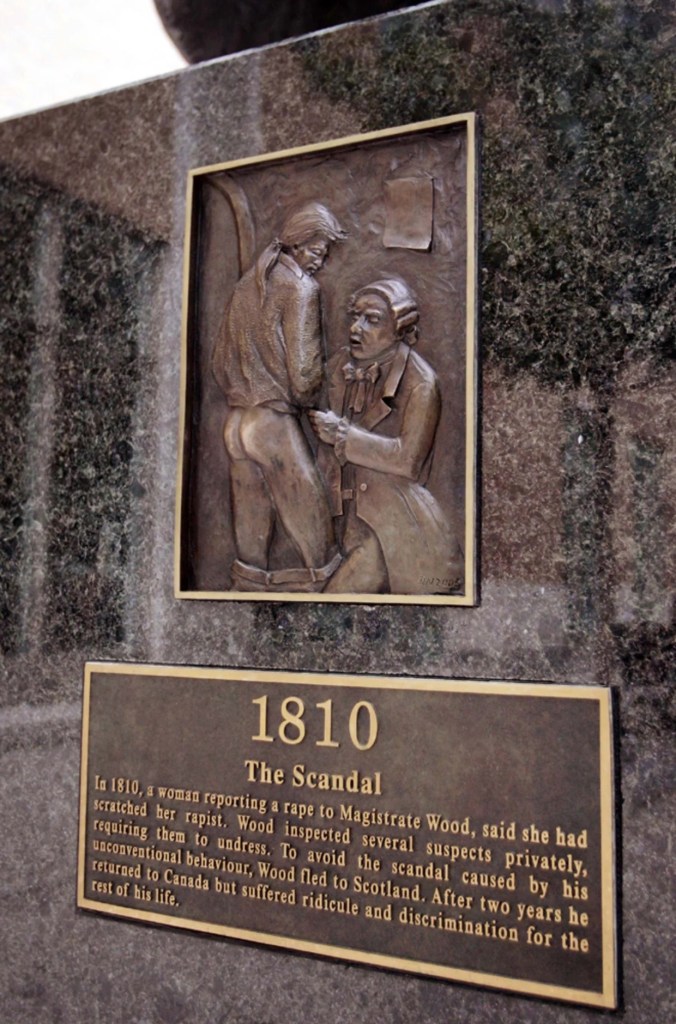

At the base of the statue was a plaque showing an engraved tableau: a young militia soldier with his pants partially lowered, presenting his bare buttocks for Wood’s infamous inspection. That image wasn’t part of the main statue—it was the plaque that made the scandal visually explicit.

And then came the charmingly queer detail: Newbigging openly stated that he modeled the soldier’s butt on the backside of his own partner.

A gift of love, art, and cheeky community pride.

The Village quickly embraced the statue with a sense of humor. Gay men began rubbing the bare butt on the plaque for luck, and as is always the case with bronze, repeated contact polished the metal to a gleaming shine. What started as a joke became a familiar ritual—a flirtatious, communal wink at queer history.

Placed at the entrance of Church and Wellesley, the statue served as a landmark for Toronto’s queer community. It stood in a district deeply associated with LGBTQ+ identity, activism, and resilience, marking the neighborhood with a figure reclaimed from historical shaming.

For many, it symbolized both pride and solidarity—a public monument that didn’t hide the queer interpretation but made it impossible to ignore.

Over time, the statue’s presence became more complicated. Some critiques focused on its campy sexualization or the historical uncertainty of Wood’s queerness. But a more serious criticism emerged:

Alexander Wood served on the Society for Converting and Civilizing the Indians and Propagating the Gospel Among Destitute Settlers in Upper Canada—an organization whose mission and practices were part of the colonial machinery that later contributed to the development of the Indian residential school system in Canada.

For Indigenous activists and allies, Wood’s connection to early assimilationist institutions made him an inappropriate figure for public commemoration. This dimension of his legacy was long overlooked but gained prominence in recent years as Canada confronted the deep harms of residential schools.

The statue thus became not only a queer symbol but also a site of contested memory.

When the site was sold to a condominium developer in 2022, community groups requested that the statue be relocated rather than removed. But issues of ownership, cost, and ongoing controversy complicated the process.

The statue was taken down quietly.

Placed in storage.

And ultimately destroyed—a loss that felt abrupt and painful to those who viewed it as a cornerstone of Village identity.

The Alexander Wood statue existed at the crossroads of queer reclamation, artistic expression, colonial history, and community identity. Its destruction leaves a literal void in the Village streetscape—a reminder that public memory is fragile and often shaped by forces beyond our control.

The polished bronze butt on the plaque may be gone, but the story remains:

of queer history reclaimed, contested, celebrated, and sometimes lost

And maybe that is the nature of queer memory itself—surviving in the stories we continue to tell.