“If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England.”

— Rupert Brooke, “The Soldier”

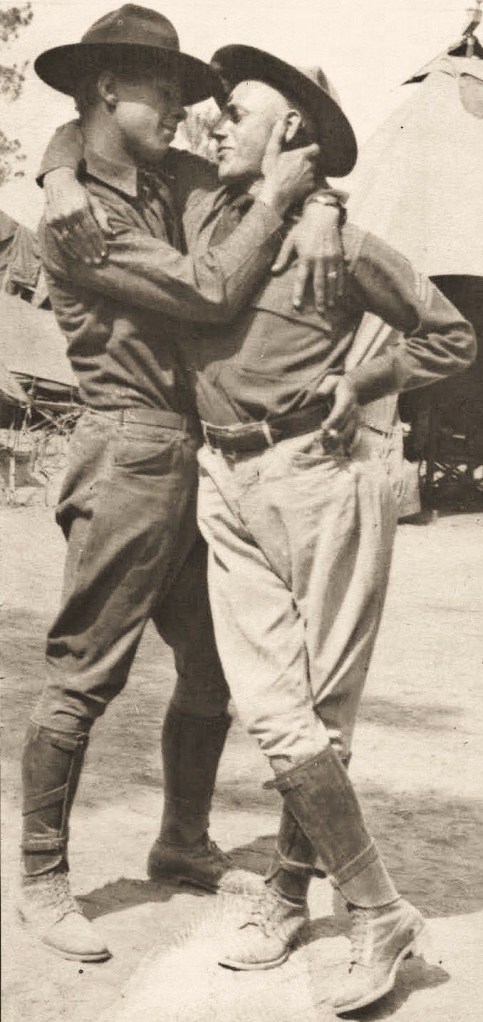

Each year on November 11, we pause to honor the men and women who have served in the armed forces. Known originally as Armistice Day, this date marks the end combat for World War I in 1918, when the guns finally fell silent on the Western Front. What began as a commemoration of peace after “the war to end all wars” evolved into Veterans Day in the United States—an annual moment of gratitude for all who have worn the uniform.

World War I not only reshaped geopolitics and society; it also transformed art and literature. Poetry, in particular, became the most immediate and emotional record of soldiers’ experiences. From the idealism of 1914 to the disillusionment of the trenches, poets captured both the nobility and the horror of modern warfare. Three poems—Rupert Brooke’s “The Soldier,” John McCrae’s “In Flanders Fields,” and Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est”—trace the arc of changing attitudes among soldiers during the Great War.

⸻

The Soldier

By Rupert Brooke

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England’s, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

⸻

Rupert Brooke’s “The Soldier” (1914) reflects the early optimism of Britain’s entry into the war. Written before he ever reached the front lines, Brooke’s sonnet presents death in battle as noble and redemptive. The poem imagines the fallen soldier as eternally consecrating foreign soil with his English spirit—a vision steeped in idealism and romantic patriotism.

Brooke’s language is pastoral and spiritual: England is “richer dust,” “flowers,” and “laughter.” His tone conveys the belief that sacrifice in service of one’s country was beautiful and pure. Tragically, Brooke never witnessed the grim realities of trench warfare; he died of blood poisoning in 1915 on his way to Gallipoli. For many early in the war, his poems embodied a kind of naïve heroism that would soon fade in the face of unimaginable loss.

⸻

In Flanders Fields

By John McCrea

In Flanders fields, the poppies blow Between the crosses, row on row, That mark our place; and in the sky The larks, still bravely singing, fly Scarce heard amid the guns below. We are the Dead. Short days ago We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, Loved and were loved, and now we lie, In Flanders fields. Take up our quarrel with the foe: To you from failing hands we throw The torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die We shall not sleep, though poppies grow In Flanders fields.

⸻

By 1915, the tone of war poetry had begun to darken. Canadian army doctor John McCrae wrote “In Flanders Fields” after presiding over the funeral of a friend who died in battle. The poem’s haunting image of red poppies growing among soldiers’ graves made it one of the most famous pieces of war poetry ever written.

“In Flanders Fields” bridges two worlds: the patriotic call of Brooke’s generation and the emerging sorrow of a war that had already claimed millions. McCrae gives voice to the dead, who urge the living to “take up our quarrel with the foe.” Yet the repetition of poppies and crosses hints at the futility of such endless sacrifice. The poem’s enduring symbol—the poppy—has become a global emblem of remembrance, worn each November to honor veterans and the fallen alike. McCrae himself died of pneumonia in 1918, just months before the war ended.

⸻

Dulce et Decorum Est

By Wilfred Owen

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame, all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin,

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer,

Bitter[note 1] as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,–

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

⸻

If Brooke and McCrae wrote from faith and duty, Wilfred Owen wrote from the mud, blood, and gas-filled trenches of the Western Front. His poem “Dulce et Decorum Est” (“It is sweet and fitting [to die for one’s country]”) exposes the brutal truth behind that patriotic ideal. Owen describes exhausted soldiers “bent double, like old beggars under sacks” and a gas attack that leaves a comrade “guttering, choking, drowning.”

By ending the poem with the biting phrase “The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori,” Owen rejects the glorification of war that poets like Brooke once embraced. His work gives a voice to the generation that witnessed industrialized slaughter on a scale never before seen. Owen was killed in action in November 1918—just one week before the Armistice.

During World War I, poetry became both a weapon and a refuge. Soldiers scribbled verses in trenches, hospitals, and letters home, using poetry to process trauma, question authority, and preserve humanity amid chaos. Newspapers published patriotic sonnets beside dispatches from the front, and later, the war poets’ raw testimonies helped shape public memory of the conflict.

The evolution from Brooke’s idealism to Owen’s bitter realism mirrors society’s loss of innocence. Through their words, we witness not just the cost of war, but the courage to speak truth against false glory.

The armistice signed on November 11, 1918, marked not only the end fighting in World War I but also the birth of a day of remembrance. In 1954, the United States renamed Armistice Day as Veterans Day to honor all those who have served, in every war and in peacetime. The poetry of Brooke, McCrae, and Owen reminds us why this day endures—not merely as a celebration of victory, but as a solemn reflection on sacrifice, service, and the cost of freedom.

A century later, these poems still speak across the silence of the graves and trenches. Brooke reminds us of the hope that sends soldiers to battle; McCrae gives us the grief that lingers after; Owen forces us to confront the truth of what war does to the human soul. Together, they form a poetic memorial as powerful as any monument of stone—a reminder that remembrance begins not with ceremony, but with empathy.

So this Veterans Day, as poppies bloom once more in our collective memory, may we honor not only the fallen, but also the living—those who have carried the burdens of service with courage, faith, and love.