In more modern times, the United States and most countries of the world criminalized homosexuality (sodomy) and therefore banned gay men and women from serving in the military. The Mattachine Society, founded in 1950, was one of the earliest homophile (gay rights) organizations in the United States, probably second only to Chicago’s short-lived Society for Human Rights (1924). Harry Hay and a group of Los Angeles male friends formed the group to protect and improve the rights of homosexuals. Because of concerns for secrecy and the founders’ leftist ideology, they adopted the cell organization of the Communist Party. In the anti-Communist atmosphere of the 1950s, the Society’s growing membership substituted a more traditional ameliorative civil rights leadership style and agenda for the group’s early Communist model. Then as branches formed in other cities, the Society splintered in regional groups by 1961.

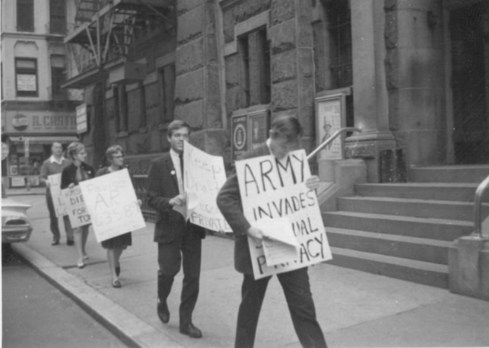

Youths rebelled against older homophile organization, which often refused to take a stance on the Vietnam War. Young gay men had to chose whether or not to reveal or conceal their homosexuality when they came before the draft board, because with the draft board being composed of local citizens, this could mean being outed to friends, neighbors or parents. The dilemma faced by gay youths polarized the gay liberation movement and gay youths joined in on the antiwar protests.[1] While older homophile organizations saw non-participation of homosexuals in the American military as detrimental to gay rights, youths of the antiwar stance saw it as a positive good. Suran contends that there are four major assertions by gay men in the antiwar movement. First, young homophiles saw military service as politically and morally counterproductive. Second, they declared war as a masculine affront to gay men. They cited the “effiminist” nature of homosexual men and refused to participate in macho role playing. Third, the young activists viewed imperialism as an extension of heterosexist ideology. Finally, they perceived homosexuality itself as antiwar antiestablishment, and anti-imperialist. With these four beliefs, young homophiles refused to embrace the older homophile tradition of assimilation in to “normal” society through military service.[2]

Though the Mattachine Society fell apart by the 1970s, one of their focuses was on protesting the US policy against gays serving in the military. They believed they could serve their country in any capacity, whether it be in government (gay men and women were not allowed to serve in government positions because their sexuality could be used as a basis for blackmail by communist spies) or in the military.

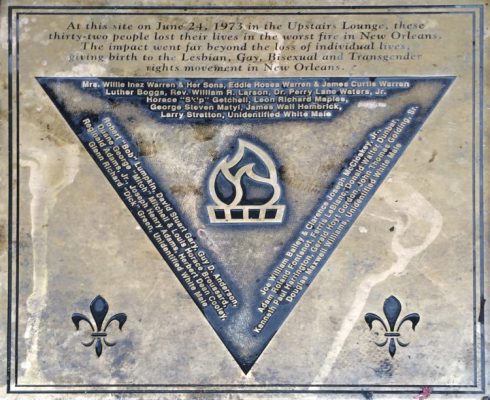

When more public gay rights groups formed after the 1969 Stonewall Riots, image gay men had moved away from support for military service. With the Vietnam War and the draft still very much a reality, gay rights groups turned their backs on the issue of military service because they did not want to be drafted. However, the government also turned their backs on the ban and forced many gay men who were drafted to serve, deciding that they needed the manpower more than they needed to uphold the ban on military service. In the United States today, sodomy is no longer illegal thanks to the Supreme Court decision, Lawrence v. Texas, and in 1973 the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Therefore there is no legal or medical reason that can be used to deny gay men and women the right to serve openly in the military.

image

[1]Justin David Suran, “Coming Out Against the War: Antimilitarism and the Politicization of Homosexuality in the Era of Vietnam,” American Quarterly 53, no. 3 (2001): 453.

[2]Ibid., 471-472.

Next: The Stonewall Riots