Monthly Archives: September 2020

To Boldly Go…

There are a lot of Star Trek fans out there who hate Star Trek: Discovery, but those same people have hated every new Star Trek series and movie. Some fans you can never make happy. However, while the Star Trek universe is one of diversity, equality, and free of discrimination, there have always been those who fought against that vision because the Star Trek universe really does boldly go where no show has gone before. Star Trek has continually broken barriers, but Star Trek: The Original Series (1966–1969), Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987–1994), Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1993–1999), Star Trek: Voyager (1995–2001), and Enterprise (2001–2005) all held back on the topic of LGBTQ+ individuals.

It was rumored throughout the production of Enterprise that there would be a gay cast member, but it never materialized. Deep Space Nine did feature a same-sex kiss in theepisode “Rejoined” (Season 4, Episode 6). The episode first aired on October 30, 1995, and the kiss was between two female characters: Lieutenant Commander Jadzia Dax and scientist Lenara Kahn. Both characters were members of the Trill society, and the kiss was not meant to be a lesbian kiss. Let’s just say, it was complicated because they were a joined species.

However, Discovery has gone where no Star Trek has gone before with LGBTQ+ characters. The premiere of Discovery included a very prominent male same-sex couple, Lt. Commander Paul Stamets and Dr. Hugh Culber, who are played by openly gay actors Anthony Rapp and Wilson Cruz. The two characters kissed shared the first gay kiss in Star Trek history near the end of season one. The show also featured a widowed lesbian engineer, Denise “Jett” Reno, played by out actress Tig Notaro. Season 3 of Discovery premiers on October 15 and will introduce the 54-year-old sci-fi franchise’s first-ever transgender and non-binary characters. Like Stamets, Culber, and Reno, the characters will be played by actors who are LGBTQ+. In fact, the actors actually are trans and non-binary in real life.

Trans actor Ian Alexander will play Gray, a Trill, the same species as Jadzia Dax and Lenara Kahn. Non-binary actor Blu del Barrio will make their debut by playing the non-binary character Adira, an intelligent and introverted teenage amnesiac whose coming-out story will mirror del Barrio’s own real-life coming out. They will befriend Discovery’s gay couple, Stamets and Culber.

Del Barrio told GLAAD, “I honestly cannot speak highly enough of Ian. I absolutely love him, and it was so fun working alongside him. Having him join the show with me was a godsend.” Del Barrio continued, “It’s pretty overwhelming joining a show with such a well-known cast going into its third season. So, I was so thankful to have his support whenever I was freaking out. He’s a talented, hardworking actor, and an all-around magnificent human being, so it was a joy having him as a partner.”

I think it is wonderful that Discovery continues to feature inclusivity in the show. The third season of the series follows the crew of the USS Discovery transported 930 years into the future and among a highly advanced but troubled society in dire need of their help. It appears that the Federation is only a shadow of its former self. The above trailer for the season depicts a Federation banner from the future with just six stars, suggesting only a handful of planets remain as part of the organization. The trailer also suggests that Starfleet no longer exists. In the preview, David Ajala’s Cleveland Booker notices Burnham’s emblem and refers to Starfleet as a “ghost.” The rest, we will just have to wait until October 15 to see what’s going to happen. If it’s anything like previous seasons, we won’t fully know what’s going on until at least several episodes into the season.

Three Wishes

If wishes were horses, beggars would ride.

—Scottish proverb

If turnips were watches, I’d wear one by my side.

If “ifs” and “ands” were pots and pans,

There’d be no work for tinkers’ hands.

I grew up watching reruns of I Dream of Jeannie and Bewitched. I’ll admit I often dreamed of either having my own Jeannie like Tony Nelson or having magical powers like Samantha Stephens. When I was bullied in school, my favorite fantasy was that with a twitch of my nose, a quick nod of my head, or even a wave of my hand, I could slam those bullies against the wall and cause them extreme pain. That may sound pretty violent, but I wanted the magical powers so that they would remember the pain but have no lasting effects from it. Maybe then, they would learn the pain they caused others. It was a frequent fantasy of mine.

I have often wondered what I would wish for if I had just three wishes. I suspect many of us have had that thought. If I were to make a grand gesture with my wishes, I’d wish for world peace, equality and acceptance for all, and that people would get the chance they deserve in life. That last one could backfire as in the old three wishes jokes. The three wishes joke (or genie joke) is a joke in which a character is given three wishes by a genie and fails to make the best use of them. Typical scenarios include releasing a genie from a lamp or crossing paths with the devil. The first two wishes go as expected in the jokes, with the third wish being misinterpreted or granted in an unexpected fashion that doesn’t reflect the wish’s intent.

Suppose I were to be purely selfish with my wishes. In that case, I’d wish to be the man I always dreamed of being: more intelligent*, taller, more handsome, physically fit with a great butt, a great head of hair, one skin tone (my vitiligo is another source of embarrassment for me), and like most men, more endowed. The second wish would be to have all the money I’ll ever need in life. I wouldn’t need to be a billionaire, just wealthy enough to live very comfortably, not have to work, and be able to travel the world. My final wish would be to find the love of my life and live happily ever after with him.

For my whole life, when I have seen the first star of the night, I have always said silently to myself:

Starlight, star bright,

The first star I see tonight;

I wish I may, I wish I might,

Have the wish I wish tonight.

Since I was a teenager, I have always secretly said the same wish each time: to find someone who I will fall in love with and vice versa. This particular wish was partially how I dealt with my burgeoning sexuality. Part of my wish was always that if it was a man, then I’d know it was the right thing, and if it was a woman, then that was the right thing. Now I simply just wish for the man of my dreams, someone I will have a wonderful relationship with for the rest of our lives. So far, it hasn’t come true, but I will keep wishing on that star.

Of course, I have had various other wishes throughout my life. I’ve wished that loved ones who have died were alive again. I’ve wished that I had met friends earlier in life. I’ve wished that my parents were more accepting of my sexuality. At times, I even wished that I were dead; depression will do that to you. Of course, I’ve also wished that I had finished my Ph.D., or that I could become a perpetual student and travel the world learning new things. I’ve even wished for awful things to happen to our current president and his soulless minions. While I’d love to have three wishes, I’m not sure if I would take the selfless route or the selfish route, but I wouldn’t want to be greedy and have an endless supply of wishes. Maybe five or six wishes would be enough.

If you had three wishes and only three wishes, what would they be? Would you benefit yourself or help others? Would you advance your career, health, or financial well-being, or would you further your social, emotional, or spiritual needs? Would you blow through your wishes right away, or would you hold a few in reserve? You may be thinking this is a silly or cliché question, but our answers can be quite telling. For example, what do your wishes say about your priorities? Do they focus on possessions or enhance your relationships? What do your wishes say about your current situation versus your ultimate goals? Are your wishes far-fetched or clearly within your grasp?

*By “more intelligent,” I mean that I wish I could read quicker (I’ve always been a slow reader) and retain more of what I read. If you were to get to know me in person, you’d find out that I have a LOT of trivial knowledge in my head that emerges at random intervals. However, I am terrible with dates and names. For a historian, my mind is not chronological. I get mixed up on things very easily.

Victory Over Japan Day

It started 81 years ago yesterday with the German invasion of Poland and ended 75 years ago today with Japan signing the Instrument of Surrender. World War II was the bloodiest conflict in human history. The world breathed an enormous collective sigh of relief. Celebrations broke out across the free world as a result of the war finally and truly being over. The dark war years gave birth to a new, optimistic future as the world looked hopefully towards an existence without world wars and massive human suffering.

Seventy-five years ago today, the formal ceremonies marking Japan’s surrender, took place aboard the USS Missouri. Early on Sunday, September 2, 1945, aboard the new 45,000-ton battleship USS Missouri and before representatives of nine Allied nations, the Japanese signed their surrender. At the ceremony, General Douglas MacArthur stated that the Japanese and their conquerors did not meet “in a spirit of mistrust, malice or hatred but rather, it is for us, both victors and vanquished, to rise to that higher dignity which alone benefits the sacred purposes we are about to serve.”

Despite these words, none of the high-ranking officers saluted any of the Japanese delegates. General Carl A. Spaatz later revealed that US planes had been ready with bombs to halt any last-minute treacherous act by Japan. Seeing a deck full of high-ranking Allied officers on the USS Missouri might have presented a tempting target for a final suicide attack.

Why was the USS Missouri chosen as the location for the Japanese surrender to take place? After all, the battleship had served for less than a year in the Pacific War. It was the last battleship commissioned into the United States Navy, although not the last laid down. The Missouri participated in several operations in the last year of the war, including the bombardments of Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and Japan. For the rest of the time, she escorted US carrier groups, protecting them from attacks. In May 1945, the Missouri became the flagship for Admiral Bull Halsey’s 3rd Fleet. In this capacity, Missouri led the Allied armada that entered Tokyo Bay on August 29, 1945.

Numerous distinguished ships were present at the surrender. The USS South Dakota had perhaps the most illustrious record among the battleships, having served in the Pacific theater since 1942. The USS West Virginia had survived Pearl Harbor. The HMS Duke of York and the HMS King George V each had sunk a German battleship (the Scharnhorst and the Bismarck, respectively). The Japanese ship HIJMS Nagato and a few other Japanese ships were also present. The ships most responsible for the Allied victory over Japan, the fleet carriers of the US Navy, remained at sea during the surrender, in effect guaranteeing Japanese compliance. The single most deserving ship, USS Enterprise, had suffered kamikaze damage late in the war and was off the coast of Washington state.

So, why the Missouri, a ship that had a respectable but not particularly distinguished war record? The quickest answer is that she was the Third Fleet’s flagship and that it made the most sense to have the surrender ceremony on the flagship. Also, President Harry S Truman had a personal connection with the ship. His daughter, Margaret, had christened the hull at its launching, and Truman hailed from Missouri, which is the likely reason for the ship being chosen. It is also worth noting that Missouri had more available deck space than most of the other options.

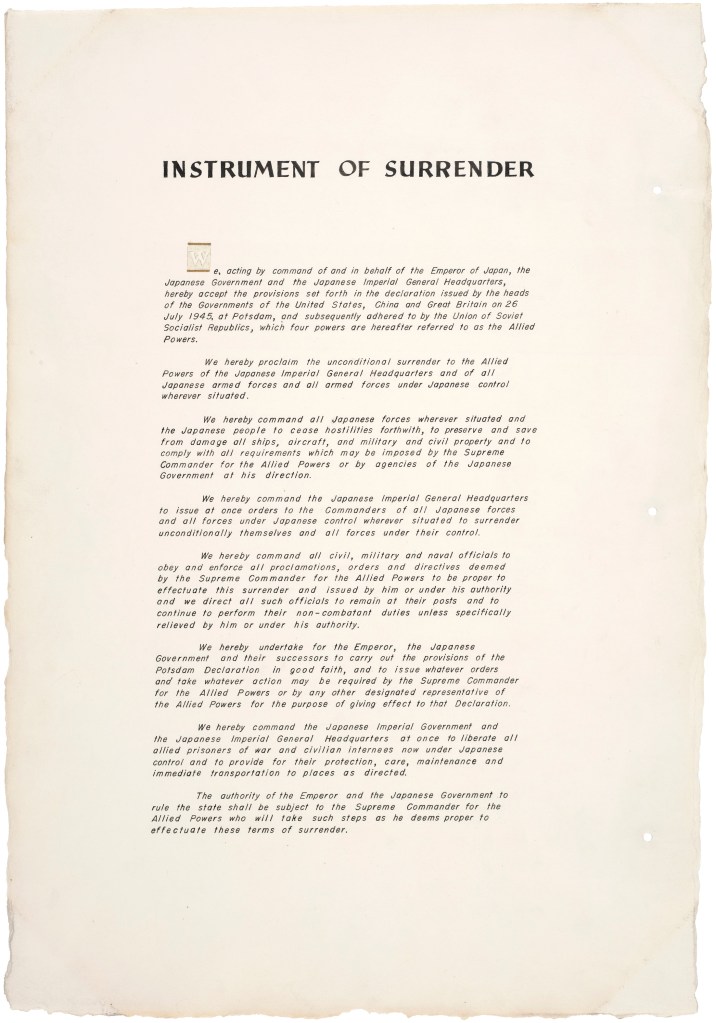

With the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay as the setting, the Japanese representatives signed the official Instrument of Surrender, prepared by the War Department, and approved by President Truman. It set out in eight short paragraphs the complete capitulation of Japan. The opening words, “We, acting by command of and in behalf of the Emperor of Japan,” signified the importance attached to the Emperor’s role by the Americans who drafted the document. The short second paragraph went straight to the heart of the matter: “We hereby proclaim the unconditional surrender to the Allied Powers of the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters and of all Japanese armed forces and all armed forces under Japanese control wherever situated.”

The Japanese envoys Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu and General Yoshijiro Umezu signed their names on the Instrument of Surrender. The time was recorded as 4 minutes past 9 o’clock. Afterward, General Douglas MacArthur, Commander in the Southwest Pacific and Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, also signed. He accepted the Japanese surrender “for the United States, Republic of China, United Kingdom, and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and in the interests of the other United Nations at war with Japan.”

After the formal surrender, investigations into Japanese war crimes began quickly, and many members of the imperial family pressured Emperor Hirohito to abdicate. However, at a meeting with the Emperor later in September, General MacArthur assured him he needed his help to govern Japan, and so Hirohito was never tried. Legal procedures for the International Military Tribunal for the Far East were issued on January 19, 1946, without any imperial family member being prosecuted. Following the signing of the instrument of surrender, several other surrender ceremonies took place across Japan’s remaining holdings in the Pacific from September 2-12.

The logistical demands of the surrender were formidable. After Japan’s capitulation, more than 5.4 million Japanese soldiers and 1.8 million Japanese sailors were taken prisoner by the Allies. The damage done to Japan’s infrastructure, combined with a severe famine in 1946, further complicated the Allied efforts to feed the Japanese POWs and civilians. It was not until 1947 that all prisoners held by the United States and Great Britain were repatriated. As late as April 1949, China still held more than 60,000 Japanese prisoners.

The state of war between most of the Allies and Japan officially ended when the Treaty of San Francisco took effect six and a half years later on April 28, 1952. Japan and the Soviet Union formally made peace four years later, when they signed the Soviet–Japanese Joint Declaration of 1956.

In his speech announcing the signing of the Instrument of Surrender, Truman honored the sacrifices made during the war:

Our first thoughts, of course — thoughts of gratefulness and deep obligation — go out to those of our loved ones who have been killed or maimed in this terrible war. On land and sea and in the air, American men and women have given their lives so that this day of ultimate victory might come and assure the survival of a civilized world. No victory can make good their loss.

We think of those whom death in this war has hurt, taking from them fathers, husbands, sons, brothers, and sisters whom they loved. No victory can bring back the faces they long to see.

Only the knowledge that the victory, which these sacrifices have made possible, will be wisely used can give them any comfort. It is our responsibility – ours, the living – to see to it that this victory shall be a monument worthy of the dead who died to win it.

Indeed, we should never forget the sacrifices of the men and women who died in the Second World War.

September 1, 1939

September 1, 1939

By W. H. Auden – 1907-1973

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odour of death

Offends the September night.

Accurate scholarship can

Unearth the whole offence

From Luther until now

That has driven a culture mad,

Find what occurred at Linz,

What huge imago made

A psychopathic god:

I and the public know

What all schoolchildren learn,

Those to whom evil is done

Do evil in return.

Exiled Thucydides knew

All that a speech can say

About Democracy,

And what dictators do,

The elderly rubbish they talk

To an apathetic grave;

Analysed all in his book,

The enlightenment driven away,

The habit-forming pain,

Mismanagement and grief:

We must suffer them all again.

Into this neutral air

Where blind skyscrapers use

Their full height to proclaim

The strength of Collective Man,

Each language pours its vain

Competitive excuse:

But who can live for long

In an euphoric dream;

Out of the mirror they stare,

Imperialism’s face

And the international wrong.

Faces along the bar

Cling to their average day:

The lights must never go out,

The music must always play,

All the conventions conspire

To make this fort assume

The furniture of home;

Lest we should see where we are,

Lost in a haunted wood,

Children afraid of the night

Who have never been happy or good.

The windiest militant trash

Important Persons shout

Is not so crude as our wish:

What mad Nijinsky wrote

About Diaghilev

Is true of the normal heart;

For the error bred in the bone

Of each woman and each man

Craves what it cannot have,

Not universal love

But to be loved alone.

From the conservative dark

Into the ethical life

The dense commuters come,

Repeating their morning vow;

“I will be true to the wife,

I’ll concentrate more on my work,”

And helpless governors wake

To resume their compulsory game:

Who can release them now,

Who can reach the deaf,

Who can speak for the dumb?

All I have is a voice

To undo the folded lie,

The romantic lie in the brain

Of the sensual man-in-the-street

And the lie of Authority

Whose buildings grope the sky:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police;

We must love one another or die.

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

“September 1, 1939,” as its title signals, was written by W.H. Auden in the days immediately following Germany’s invasion of Poland, which marked the start of World War II. Auden had left his native England and moved to New York City some nine months earlier, and the famous opening lines of the poem are rooted in the dingy geography of his new home.

This poem achieved great resonance after the events of September 11, 2001—it was widely reproduced, recited on NPR, and interpreted with a link to the tragic events of that day. But it captured Auden’s reaction to the outbreak of World War II. The poem expresses anger and sadness towards those events, and it questions the historical and mass psychological process that led to the war. It focuses on the political psychosis of the German people, echoing a few lines of Nietzsche (“Accurate scholarship can / Unearth the whole offence / From Luther until now / That has driven a culture mad”). It then turns to the effect that this war will have on the world and its people, again with psychological overtones.

The poem was first published on 18 October 1939 in the American magazine, the New Republic. Auden had arrived in New York with his friend and fellow writer Christopher Isherwood. The two men quickly established themselves on the US literary scene: schmoozing, partying, making contact with editors, and undertaking speaking and lecturing engagements. In April 1939, Auden had met an 18-year-old, Chester Kallman, 14 years his junior, who was to become his life partner: in the new world, Auden was making a new life for himself. Back in Europe, meanwhile, the storm clouds were gathering.

W. H. Auden wrote the poem while visiting the father of his lover Kallman in New Jersey. Dorothy Farnan, Kallman’s father’s second wife, in her biography Auden in Love (1984), wrote that it was written in the Dizzy Club, an alleged gay bar in New York City, as if the statement in the first two lines, “I sit in one of the dives / On Fifty-second Street,” were literal fact and not conventional poetic fiction (she had not met Kallman or Auden at the time). Auden later clarified that the poem’s beginning in Manhattan, “in one of the dives on Fifty-second Street,” was, in fact, the Dizzy Club at 62 West 52nd Street.

Auden hated the poem and believed it to be of poor quality. Despite this, the poem became famous and widely popular. E. M. Forster wrote, “Because he once wrote ‘We must love one another or die’ he can command me to follow him” (Two Cheers for Democracy, 1951). Soon after writing the poem, Auden began to turn away from it, apparently because he found it flattering to himself and his readers. In 1957, he wrote to the critic Laurence Lerner, “Between you and me, I loathe that poem” (quoted in Edward Mendelson, Later Auden). He resolved to omit it from his further collections, and it did not appear in his 1966 Collected Shorter Poems 1927–1957.

In the mid-1950s, Auden began to refuse permission to editors who asked to reprint the poem in anthologies. In 1955, he allowed Oscar Williams to include it complete in The New Pocket Anthology of American Verse but altered the most famous line to read, “We must love one another and die.” Later, he allowed the poem to be reprinted only once, in a Penguin Books anthology Poetry of the Thirties (1964), with a note saying about this and four other early poems, “Mr. W. H. Auden considers these five poems to be trash which he is ashamed to have written.”