Monthly Archives: April 2025

Working Thursday

As I wrote this, I am watching the news and about to start getting ready for work. I took a vacation day yesterday trying to use up accumulated vacation time before I lose it at the end of the fiscal year (May 31). I will also be taking a vacation day tomorrow, but today I have to work. I’d have preferred to take my vacation days consecutively, but the schedules of my coworkers does not allow for that. I’m not thrilled about going to work today, but I have a few things I need to do, especially grading for my class before the semester ends. I’m a little behind in my grading.

If anyone was wondering about how the ultrasound went on Monday, they did find some stiffening of my liver which could cause problems later. My doctor said that there isn’t much to worry about at this point because it is still mild and reversible, but he wants to be aggressive in treatment and is sending me to a gastroenterologist. There is one locally, who my doctor says is the best around and has a specialty in liver disease. I don’t have an appointment yet to see this doctor, but my referral has been sent. I was initially very distressed at the results of the ultrasound, and I messaged my doctor asking how worried I should be. He called me and put my mind at ease. I am so fortunate to have a doctor who is so caring and one that I can talk to openly and honestly. I’ve had friendly doctors before, but no one I ever felt as comfortable and as confident with than I do my current doctor. Anyway, I’ll keep you posted when I know more. Right now, there isn’t much to tell.

And finally, here is your Isabella pic of the week. She let me sneak up on her while she was sleeping and take this picture. The first time I tried to take it, she looked up at me with an annoyed expression, but then, went back to sleep as cats so often do.

Pic of the Day

Framing the Male Nude

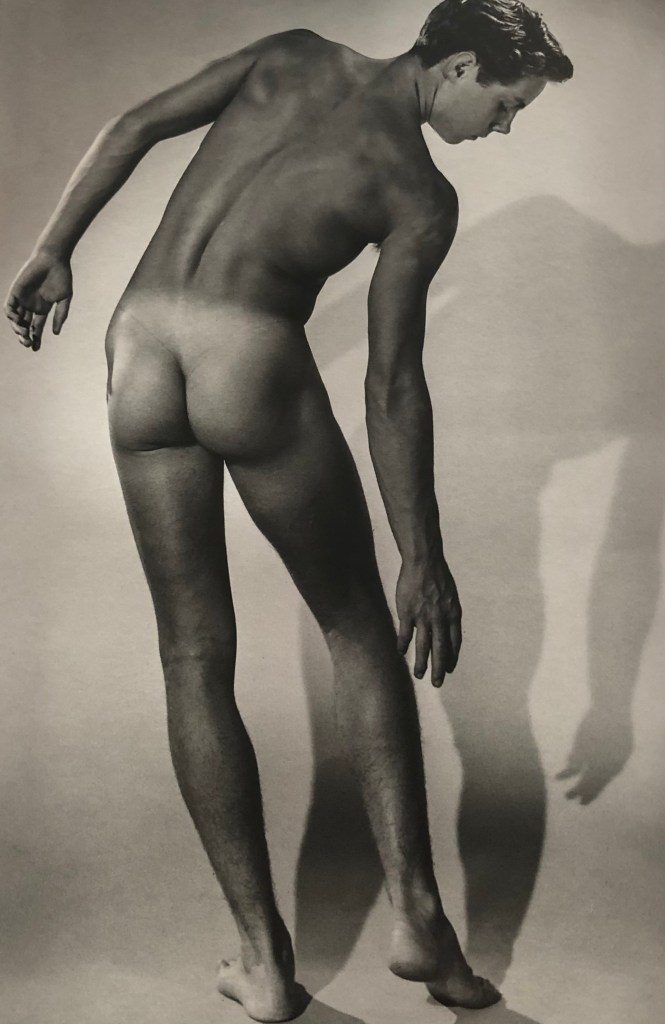

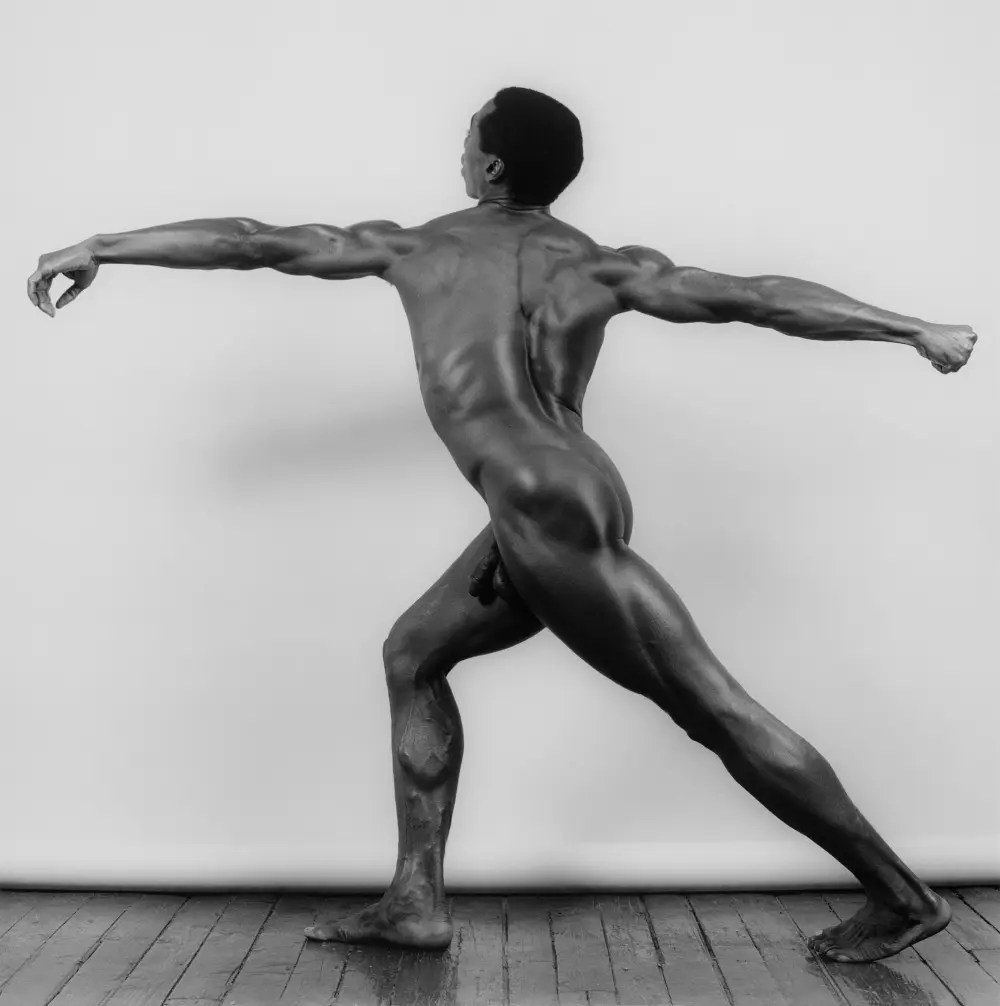

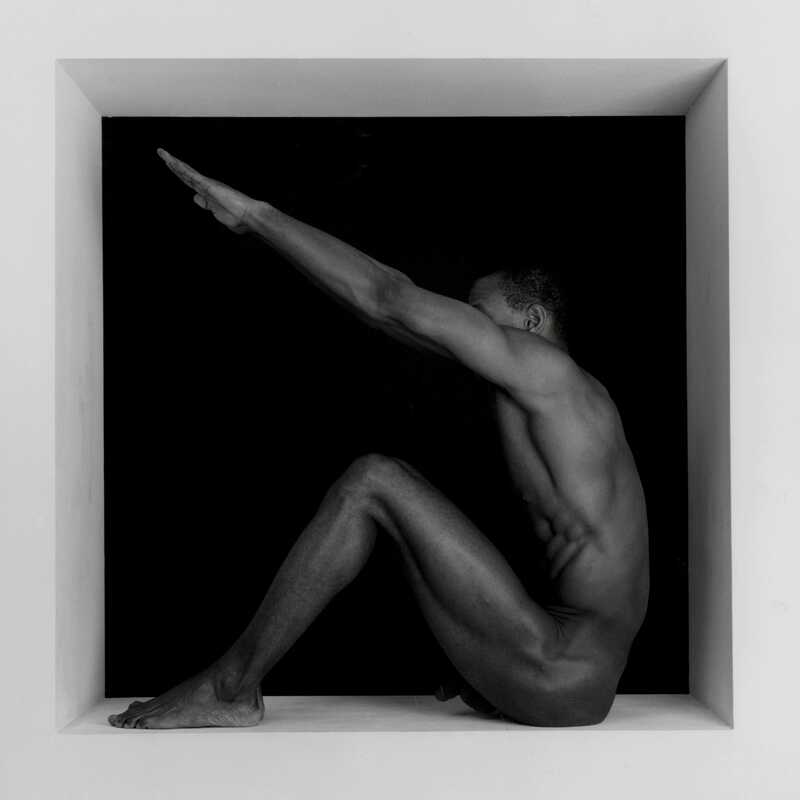

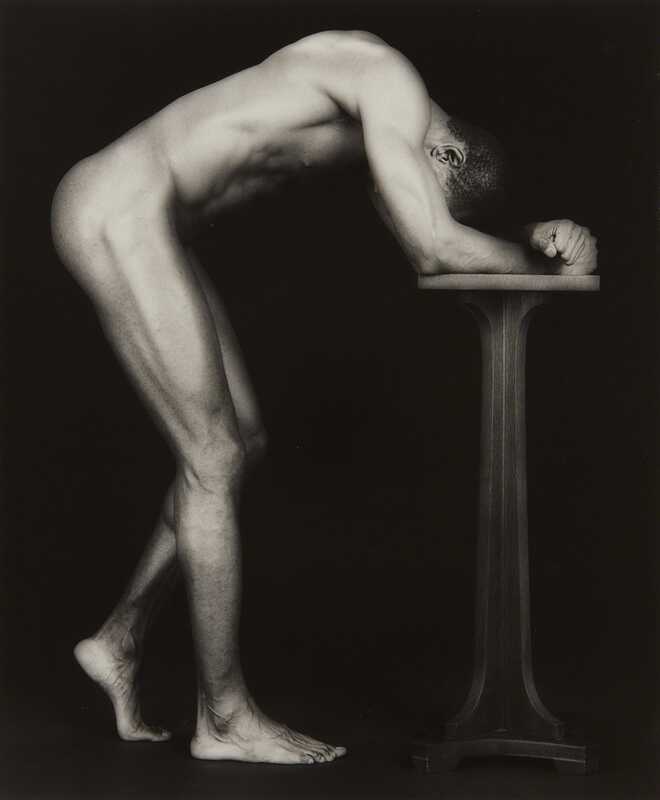

The photography of the male nude occupies a rich and multifaceted space in visual history. From its emergence in the 19th century to its entwinement with queer identity and sexual liberation in the 20th, the male nude has been variously categorized as artistic, erotic, art-erotic, or pornographic. These categories—though often overlapping—are shaped by aesthetic choices, social context, and the photographer’s intent. While definitions remain fluid, understanding their distinctions helps trace the evolution of male imagery, censorship, and desire across time.

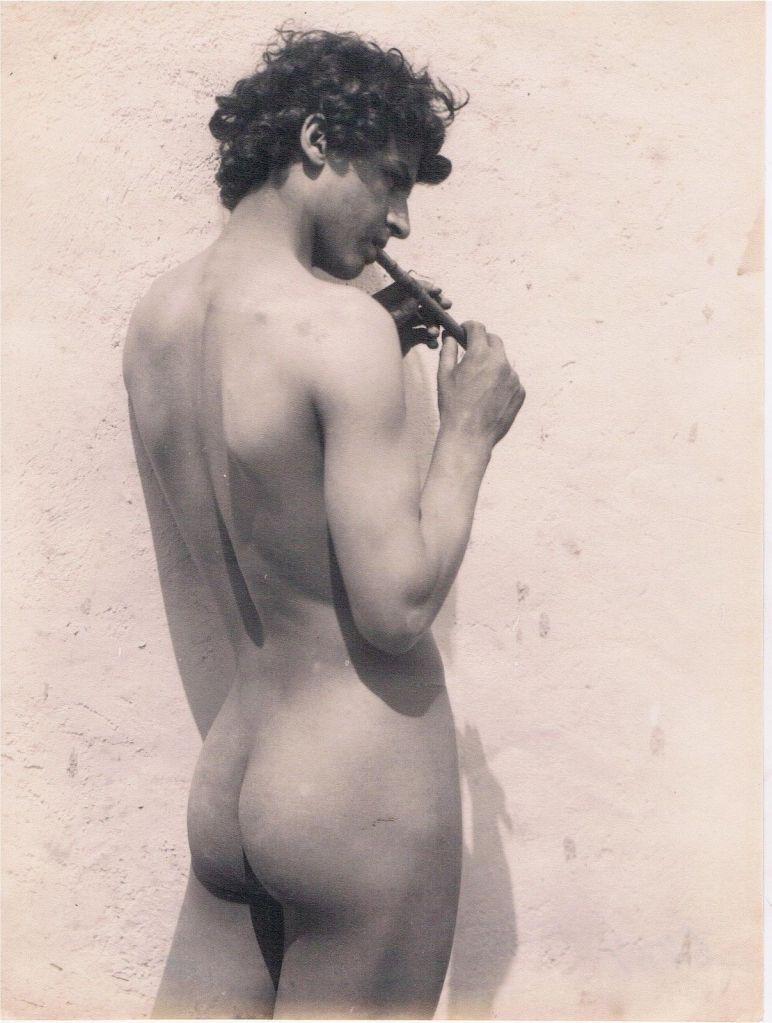

Artistic male nudes are rooted in classical ideals of beauty, proportion, and human form. These works typically present the male body as a timeless object of contemplation rather than sexual desire. Photographers such as Wilhelm von Gloeden and Guglielmo Plüschow, working in late 19th-century Italy, produced pastoral, sepia-toned images of nude youths posed against ancient ruins or natural landscapes. The subjects, often draped in togas or standing in contrapposto, evoke Hellenistic sculpture. The aesthetic was elevated, not erotic framed as reference for artists or scholars.

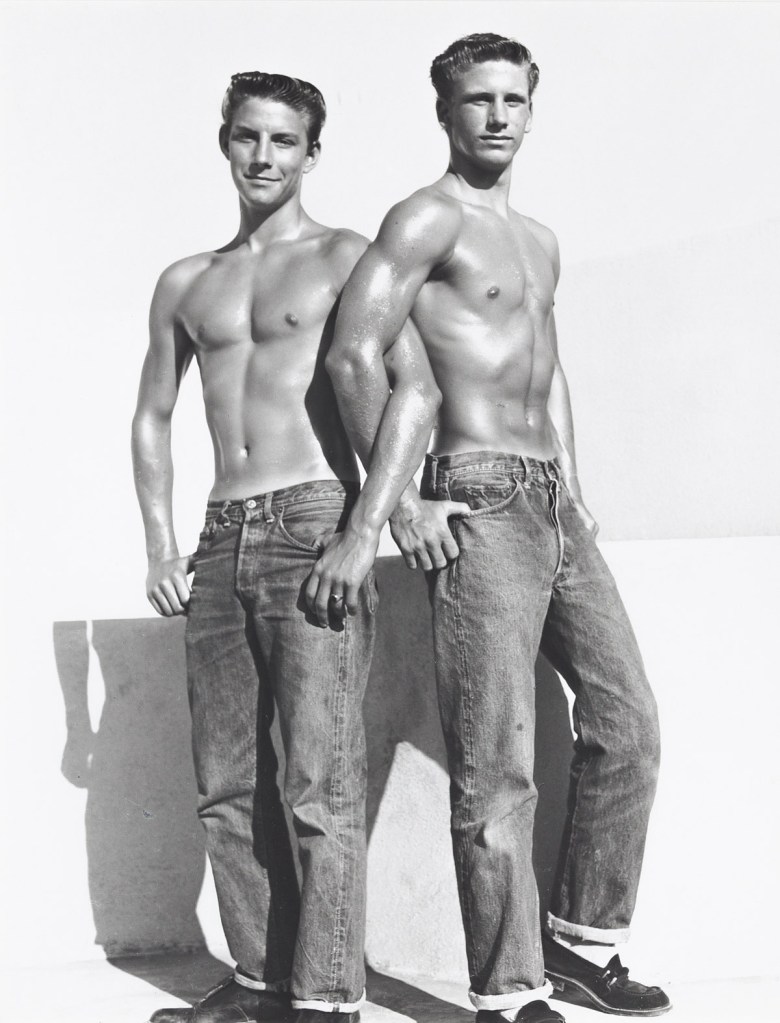

Erotic male nudes, by contrast, are designed to evoke desire. While still avoiding explicit content, they emphasize sensuality and allure. Studios like the Athletic Model Guild, founded by Bob Mizer in 1945, epitomize this genre. Mizer’s models were often young, muscular, and photographed in minimal attire—usually posing straps. Though presented as ‘model studies’ or athletic reference images, they were unmistakably charged with homoerotic appeal. A classic example is AMG model Jim Grant in 1949, his body carefully composed for aesthetic and erotic impact.

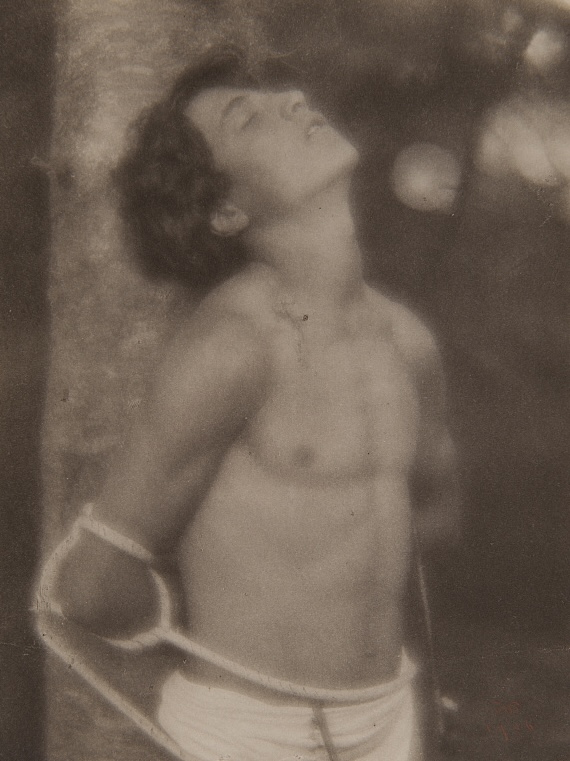

Between these poles lies the hybrid category of art-erotic nudes—images that deliberately blend aesthetic ambition with erotic suggestion. Photographer Robert Mapplethorpe redefined this space in the 1970s and ’80s. His studio portraits of Black male nudes, leather-clad figures, and homoerotic still lifes challenged museum conventions while embracing overt sensuality. His 1986 photograph of bodybuilder Thomas—posed like a neoclassical statue but fully exposed—is both starkly erotic and compositionally exquisite. Earlier precedents include F. Holland Day’s portrait of Nicola Giancola as St. Sebastian, which straddle martyrdom and homoerotic reverence.

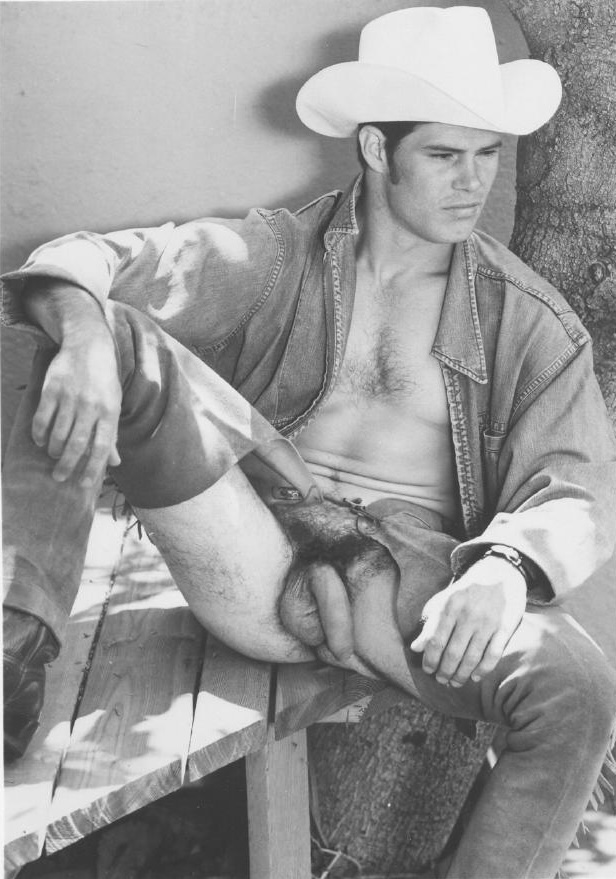

Still photo pornography occupies the far end of the spectrum, with imagery created explicitly for sexual arousal. With the loosening of obscenity laws in the 1960s and 1970s, studios like COLT, Falcon, and Target began publishing full-frontal male photography, often themed around working-class or hypermasculine fantasies. A 1970s COLT photo set of model Buddy Houston, fully nude and posed as a cowboy, exemplifies this genre. Here, the goal is no longer suggestion or metaphor, but direct sexual gratification—often accompanied by narratives or visual cues designed to stimulate.

These categories—artistic, erotic, art-erotic, and pornographic—are best understood as points along a continuum rather than rigid definitions. A single image might be interpreted differently depending on the viewer, setting, or historical moment. In 1964 United States Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart described his threshold test for obscenity in Jacobellis v. Ohio by saying:

I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description [“hard-core pornography”], and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that.

In gallery spaces, an image may be framed as art; in private, it may serve a different function altogether. For LGBTQ+ audiences, especially during eras of repression, these images carried layered meanings: as mirrors of desire, acts of defiance, and moments of recognition. Their legacy continues to shape how we view the male body, beauty, and freedom.

“Hope” is the thing with feathers

“Hope” is the thing with feathers

By Emily Dickinson

“Hope” is the thing with feathers –

That perches in the soul –

And sings the tune without the words –

And never stops – at all –

And sweetest – in the Gale – is heard –

And sore must be the storm –

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm –

I’ve heard it in the chillest land –

And on the strangest Sea –

Yet – never – in Extremity,

It asked a crumb – of me.

About the Poem

Emily Dickinson’s poem “Hope” is the thing with feathers is one of her most beloved and widely anthologized works. In it, she personifies hope as a small bird—a familiar metaphor made profound through Dickinson’s spare, enigmatic style.

At its core, this poem explores the resilience and constancy of hope, even in the face of extreme hardship. Dickinson employs her characteristic style: short lines, slant rhyme, and dashes that suggest pause and thoughtfulness. Through this seemingly simple image of a bird, she conveys a powerful and deeply felt emotional truth.

Dickinson begins with a metaphor: hope is a bird. It lives within us—“perching in the soul”—ready to lift us even when we don’t notice it. Its song has no lyrics (“sings the tune without the words”), emphasizing that hope is felt emotionally rather than intellectually. It’s also unceasing, suggesting that even in the darkest moments, it hums quietly in the background.

This second stanza emphasizes that hope is most powerful during hardship (“the Gale” symbolizing struggle). Even when storms rage, hope endures. The line “sore must be the storm / That could abash the little Bird” implies that only the gravest suffering could silence hope—yet even then, it remains difficult to truly extinguish.

In the final stanza, Dickinson draws from the natural world to show that hope has accompanied her across metaphorical landscapes of isolation, cold, and unfamiliarity. No matter how desolate or distant she has felt, hope has been present. Her final lines,

Yet – never – in Extremity, / It asked a crumb – of Me.

underscore the selflessness of hope. Unlike other comforts or companions, hope demands nothing in return. It offers its song freely.

Dickinson’s use of common meter mimics the rhythm of a hymn, reinforcing a spiritual dimension (in music, the most common meter is 4/4*). The use of dashes creates a meditative, breath-like pacing, and her idiosyncratic capitalization imbues certain words (like “Hope,” “Gale,” “Bird”) with almost symbolic weight.

Dickinson, a poet known for her reclusiveness and introspection, often explored intangible inner states. Here, hope becomes both fragile and formidable—a quiet but persistent companion. The poem has a soothing, almost lullaby-like quality, which makes it deeply comforting to readers experiencing doubt, fear, or grief.

“Hope” is the thing with feathers is a deceptively simple poem, yet it speaks profoundly to the indomitable spirit of the human heart. Dickinson’s ability to express such depth in such few words is part of what makes her work timeless. The image of a bird quietly singing through storms and over seas remains one of the most enduring representations of hope in all of American poetry.

—

The common meter in music is 4/4. Songs such as “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” “The Yellow Rose of Texas,” The House of the Rising Sun,” and the theme song to Gilligan’s Island. Therefore, nearly all of Dickinson’s poems, most of which are in common meter, can be sung to the tune of any of these songs.

About the Poet

Emily Dickinson (1830–1886) was an American poet known for her reclusive life and innovative, deeply introspective verse. Born in Amherst, Massachusetts, into a prominent and well-educated family, she received a strong early education and briefly attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary. Though she rarely left her hometown, Dickinson maintained a rich inner world and corresponded widely with friends, relatives, and literary figures. Her poetry, characterized by its compressed style, slant rhyme, and idiosyncratic punctuation, often explored themes of nature, death, love, faith, and the soul.

During her lifetime, only a handful of Dickinson’s nearly 1,800 poems were published—and often heavily edited to fit conventional 19th-century poetic norms. After her death in 1886, her sister Lavinia discovered her cache of handwritten poems and worked with editors to bring them to the public. Over time, Dickinson’s originality and brilliance were recognized, and she came to be regarded as one of the most important figures in American literature. Her work, at once enigmatic and emotionally powerful, continues to influence poets and readers around the world.

Easter Monday

I am not Catholic, but I know many of you are. I know the news of Pope Francis’s death is affecting many today. Francis seemed to try to make the Catholic Church more welcoming and inclusive, and I know there are those who believe he did not do enough. I hope the cardinals will elect a pope who will push harder for reforms and to do more against the abuses of the church through the years. I fear they won’t, but I hope they will. My condolences today to all my Catholic friends out there. As the t-shirt on the man above says, I think Pope Francis did leave a mark on Catholic history.

In a more personal and different note, I’m having an ultrasound of my liver this morning. The blood test conducted while I was in the hospital and the CT scan that I had, showed some worrying numbers. I had already known that I have fatty liver disease, but I’ve been working on exercising more and being more careful with my diet. The CT scan showed that fatty liver may have caused some fibrosis, and so the doctors ordered a liver ultrasound and liver elastography to assess for fibrosis. I’m not too worried about this. When I saw my doctor last week, he said the numbers in my blood tests did not show signs of fibrosis, and he thought the severe numbers they saw at the hospital were because I was so sick. However, he wanted me to still have the ultrasound to be certain.

In other news, this is the last week of classes. While I have enjoyed teaching this class, it has been a lot of work. I hope I will teach this class again in the future now that I have the basics created for it. I have one more lecture tomorrow which I plan to be more of a discussion than a lecture, then it will be all about grading to finish things up.

I hope everyone has a great week! Again, my condolences to my Catholic friends out there.

From Fear to Joy

“Nothing can separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

—Romans 8:39

The days between the Crucifixion and Easter morning were dark, uncertain, and full of fear. The disciples had followed Jesus, trusted him, even left behind their old lives for him—and now he was gone. Executed as a criminal. Buried in a borrowed tomb. Their hopes were shattered. They locked themselves away in fear.

The morning of His Resurrection did not begin in joy—it began in silence, confusion, and fear. The tomb was empty. Jesus was gone. Mary wept, believing his body had been taken. The disciples, unsure of what to believe, hid behind locked doors. The world had shifted under their feet.

If you’ve ever lived in that in-between space—between grief and hope, rejection and love, silence and revelation—Easter is your story too.

The disciples would have known the words of Psalm 30:5: “Weeping may stay for the night, but rejoicing comes in the morning.” Yet in the shadow of the Crucifixion, their grief clouded their understanding. Though Jesus had spoken plainly of what was to come, sorrow and fear made it difficult for them to remember. In Luke 9:22, Jesus told them: “The Son of Man must suffer many things and be rejected by the elders, the chief priests and the teachers of the law, and he must be killed and on the third day be raised to life.”

Many gay men, too, anticipate rejection when they come out—rejection from family, faith communities, or society. Jesus predicted that He would be rejected as well. He was misunderstood by many who expected the Messiah to be a political liberator, someone who would overthrow Roman rule. Yet Jesus accepted his fate, knowing that his rejection and death would lead to something greater. In John 2:19, He said: “Destroy this temple, and I will raise it again in three days.” Though the disciples did not grasp it at the time, Jesus was preparing them for the truth that death was not the end—that from what was broken, new life would rise. By holding on to our faith after our rejection, we will be reborn and risen because while others may have rejected us, God never will.

Many gay men of faith know what it is to feel locked out or hidden away. We’ve known fear. We’ve known doubt. We’ve been told, sometimes by the church itself, that we are not fully welcome in the places where love should flourish. But in the Resurrection, God does something unexpected and deeply personal: Christ returns, not to the powerful, but to the ones who are hurting, frightened, and unsure. And he calls them by name.

He speaks Mary’s name in the garden—and suddenly, her mourning becomes recognition. John 20:16 says, “Jesus said to her, ‘Mary.’ She turned toward him and cried out… ‘Teacher!’” She turns and knew: love had not left her.

John 20:19 says, “On the evening of that first day of the week, when the disciples were together, with the doors locked for fear… Jesus came and stood among them and said, ‘Peace be with you.’” He appears to the disciples in their fear and breathes peace into the room. They do not reach out first—he comes to them.

John 20:25 tells us that Thomas doubted that Jesus had risen, “He said to them, ‘Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe.’” And when Thomas cannot believe without proof, Jesus doesn’t shame him. Instead, a week later in John 20:27, Jesus went to Thomas and said, “Put your finger here; see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it into my side. Stop doubting and believe.”

This is not the love of a distant or conditional Savior. This is a love that returns for you. A love that steps across fear, past doubt, and into locked rooms and wounded hearts. This is a Savior who speaks your name—not with judgment, but with tenderness.

No amount of uncertainty or fear can lock Christ out. His resurrection is not only about defeating death—it’s about restoring relationship. It’s about stepping into locked rooms, into quiet hearts, into hidden places, and saying, “Peace be with you.” It’s about transforming sorrow into joy.

You are not forgotten. You are not disqualified. You are not too late.

The Risen Christ sees you fully—your questions, your longings, your deepest self—and says: Peace be with you. Rejoice. I have called you by name. You are mine.

Are there places in your life where fear still holds the door closed? Have you heard Christ calling you by name—and if not, are you open to listening? What would it mean to let resurrection joy take root in your story? Christ knows what it is to be misunderstood, doubted, and abandoned. And yet, he rises not to condemn, but to comfort. He comes not to erase your wounds, but to show you his own—and in doing so, to show you that your story is safe with him. Whether you are weeping in the garden or hiding behind locked doors, he is near. He speaks your name. He breathes peace. And he turns your fear into joy.

Jesus was crucified to suffer for our sins, and He was risen from the dead to allow us to be reborn. On this Easter Sunday, remember what the angel told Mary in Matthew 28:6 when she discovered the empty tomb:

“HE HAS RISEN”