I’m sure you’ve heard this saying before about “men seldom make passes…,” but did you know that it was actually a short poem by Dorothy Parker?

News Item

By Dorothy Parker

Men seldom make passes

At girls who wear glasses.

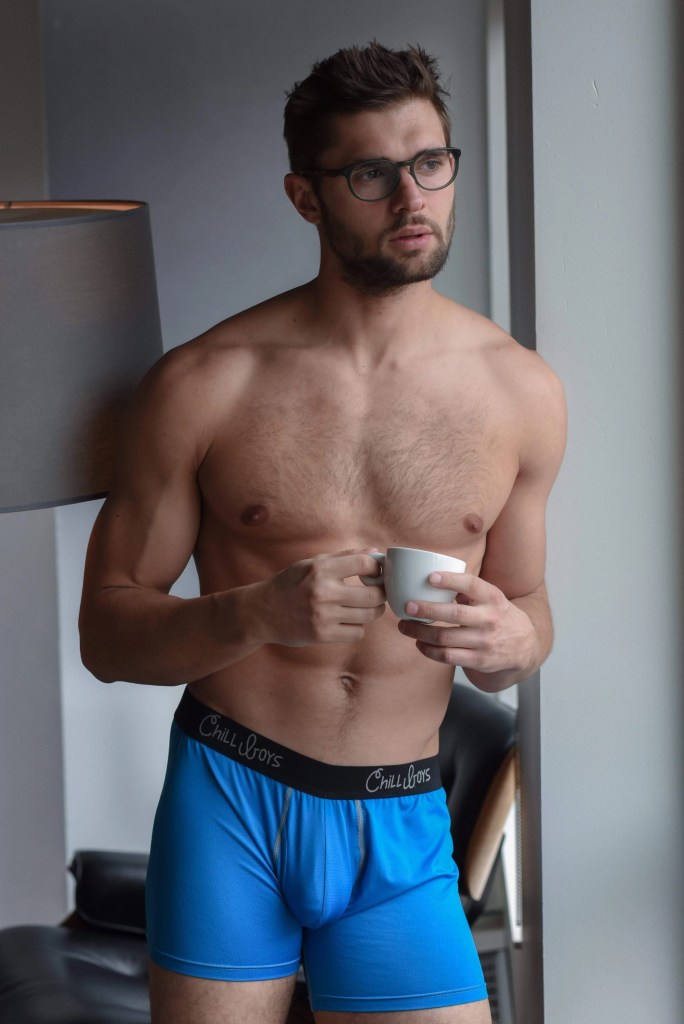

Thankfully, men do make passes at men who wear glasses, or at least, they should by the looks of these men.

I’m writing today’s post later than usual—and for good reason. As I mentioned earlier in the week, I’ve been working on a short story which has become more of a novella than a short story, and my mind was on that this morning. Also, I took the day off. Not for a big trip or even a long weekend getaway, but for something quieter, something more necessary: rest.

It’s Good Friday, a day of solemn reflection in the Christian calendar, marking the crucifixion of Jesus and the heavy silence that precedes the joy of Easter morning. Whether one observes it religiously or not, there’s something about Good Friday that invites stillness. Maybe it’s the echo of ancient grief. Maybe it’s just the gray light of early spring. But today, I let myself lean into that quiet.

I had planned to write this morning. I usually do. But after a long week—and a distracted mind—I simply forgot to write anything earlier. The temptation to fill every day with productivity is strong, even on holidays, especially when there is so much to be done, particularly the end of a very busy semester at work. But Good Friday, of all days, is a reminder that silence has its place too. That waiting is part of the story.

So, I worked on my novella. Read a few pages of a book I’ve been meaning to finish. Made tea. Watched the morning news, at least what I could stand of it. (I mute it every time the news mentions the current administration.) I simply let my mind wander.

And now, a little later than usual, I’m here—grateful for this space, for all of you who read and check in, and for the chance to slow down now and then, even if only for a moment.

Wherever you are today, and however you observe it, I hope you’re able to find a bit of rest, a breath of stillness, and maybe even a little grace.

Wishing you peace this Good Friday!

Throughout its long and culturally rich history, Florence, Italy has been a singular beacon for artistic innovation, intellectual inquiry, and—though often unspoken—a degree of sexual tolerance that fostered the flourishing of queer artistic expression. While not free of repression or societal prejudice, Florence’s nuanced approach to male same-sex desire, especially during the Renaissance, provided a relatively permissive environment in which gay artists, writers, and patrons could explore themes of male beauty and homoeroticism with a boldness rarely seen elsewhere in Europe. This openness left a profound imprint on Western art, particularly in the celebration of the idealized male nude.

Florence’s complex relationship with homosexuality begins with its legal records. In the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, Florentine officials did periodically prosecute acts of sodomy; however, these charges were often handled by a special court called the Ufficiali di Notte (Officers of the Night), which, rather than enforcing severe punishment, often issued small fines or encouraged discretion. Historians such as Michael Rocke have detailed how this legal system—while certainly functioning to monitor sexuality—also allowed a surprising degree of leeway. Rocke’s influential study, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence, documents how widespread male same-sex relations were, particularly among youths, apprentices, and even within elite circles.

This complex system of tacit tolerance allowed many artists and patrons to pursue relationships and artistic themes centered on male beauty without immediate fear of extreme censure. The Church’s looming influence often required a veil of classical or mythological allegory, but Florentine artists mastered this strategy, embedding homoerotic ideals within celebrated and culturally accepted artworks.

The Renaissance’s rediscovery of Greco-Roman ideals—particularly in Florence—led to a renewed emphasis on the idealized human form. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the explosion of male nude imagery, often clothed in mythological or biblical themes but clearly intended as a vehicle for the admiration of masculine beauty.Michelangelo Buonarroti, one of Florence’s most revered sons, was perhaps the most prominent example of this convergence of artistic genius and homoerotic expression. Deeply religious yet emotionally and artistically drawn to male beauty, Michelangelo left behind a vast body of work—both visual and poetic—that expresses intense admiration for the male form. His David (1501–1504), sculpted from a single block of marble, stands as the quintessential expression of the ideal male nude. While ostensibly a biblical hero, the sculpture’s nudity, grace, and sensuality are undeniably rooted in classical aestheticism and personal admiration.

Michelangelo’s love poems to young men like Tommaso dei Cavalieri further reveal the emotional landscape from which these artistic works emerged. Deil Cavalieri also appeared in Michelangelo’s art, such as in his 1533 drawing Il Sogno(The Dream). While the drawing is not directly linked to de’ Cavalieri, its similarity with the others has suggested to some scholars that it was connected to them. Unlike other works, the iconography does not derive from Greek mythology, and its subject is interpreted as related to beauty.

In the Medici Chapel (1520s–1530s), Michelangelo again uses male nude figures as symbolic forms in his allegorical representations of Dawn, Dusk, Night, and Day—emphasizing not only the muscular male body but also the melancholic introspection often associated with unattainable longing.

Leonardo da Vinci, though more cautious than Michelangelo, also exemplifies this phenomenon. Arrested as a young man for accusations of sodomy (which were ultimately dropped), Leonardo lived most of his life with male companions and frequently drew male nudes, many of which contain sensual, almost tender depictions of the male body. His anatomical studies, such as those housed in the Royal Collection at Windsor, reflect an obsessive and intimate familiarity with male physicality, often surpassing the scientific purpose of the sketches.

The relative tolerance of same-sex love, coupled with the city’s humanist and aesthetic philosophies, gave rise to a cultural milieu where queer-coded art could flourish under classical and religious guises. This climate, while not openly affirming, allowed for an extraordinary level of subtextual and symbolic freedom. Artists such as Donatello, whose bronze David (c. 1440s) predates Michelangelo’s and features a more androgynous, sensual portrayal, added to the lexicon of homoerotic art in Florence. The languid pose, feather-brushed thigh, and soft musculature of Donatello’s David have been widely read by scholars as a coded celebration of male eroticism.

In literature, figures like Marsilio Ficino, a Neoplatonist philosopher under Medici patronage, exalted same-sex spiritual love as part of divine beauty. Ficino’s translations of Plato’s Symposium and other works gave philosophical legitimacy to love between men, which would become a foundational element of Renaissance humanism.

This artistic tradition continued to echo well beyond the Renaissance. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Florence attracted numerous queer expatriates and artists who found inspiration and refuge in the city’s tolerant atmosphere and classical aesthetic. Figures such as Edward Perry Warren, John Addington Symonds, and even E.M. Forster spent time in Florence, drawn by its legacy of beauty, art, and the sensual freedom subtly encoded in its cultural DNA.

One of the most compelling and explicitly queer figures connected to 19th-century Florence is not Italian, but Frederick Leighton (1830–1896), the British painter and sculptor who was part of the expatriate art community in Italy. Leighton traveled extensively throughout Italy and maintained a strong relationship with Florence, where he studied and engaged with the classical tradition. Though he spent much of his later life in London, Florence was instrumental in shaping his early artistic ideals.Florence’s nuanced and historically shifting tolerance toward homosexuality enabled one of the most robust and beautiful traditions of male nudity in Western art. Through sculpture, painting, poetry, and philosophy, gay artists and patrons were able to explore male beauty not merely as a classical ideal but as a deeply personal, emotional, and sometimes spiritual pursuit. Florence stands as a historical haven—not without contradiction or repression, but with a legacy of quiet dignity and artistic boldness that continues to inspire to this day.

This will be quick. I haven’t had a chance to prepare a history/art/eroticism post for today. Hopefully, I’ll be able to post it tomorrow. In the meantime, I have a doctor’s appointment this afternoon. Some people dread going to the doctor, but I really like my doctor and always enjoy seeing him. It doesn’t hurt that he is devastatingly handsome. He’s straight and married, so I just get to admire him, but he is always so kind when I see him, and I never feel hurried or rushed when he’s seeing me. I think everything will be a good report, though we will discuss me being in the hospital.

Since I will likely post my history/art/eroticism post tomorrow, here’s is this week’s Isabella Pic of the Week:

A Certain Weariness

By Pablo Neruda

I don’t want to be tired alone,

I want you to grow tired along with me.

How can we not be weary

of the kind of fine ash

which falls on cities in autumn,

something which doesn’t quite burn,

which collects in jackets

and little by little settles,

discoloring the heart.

I’m tired of the harsh sea

and the mysterious earth.

I’m tired of chickens

we never know what they think,

and they look at us with dry eyes

as though we were unimportant.

Let us for once – I invite you –

be tired of so many things,

of awful aperitifs,

of a good education.

Tired of not going to France,

tired of at least one or two days in the week

which have always the same names

like dishes on the table,

and of getting up-what for?

and going to bed without glory.

Let us finally tell the truth:

we never thought much

of these days

that are like houseflies or camels.

I have seen some monuments

raised to titans,

to donkeys of industry.

They’re there, motionless,

with their swords in their hands

on their gloomy horses.

I’m tired of statues.

Enough of all that stone.

If we go on filling up

the world with still things,

how can the living live?

I am tired of remembering.

I want men, when they’re born,

to breathe in naked flowers,

fresh soil, pure fire,

not just what everyone breathes.

Leave the newborn in peace!

Leave room for them to live!

Don’t think for them,

don’t read them the same book;

let them discover the dawn

and name their own kisses.

I want you to be weary with me

of all that is already well done,

of all that ages us.

Of all that lies in wait

to wear out other people.

Let us be weary of what kills

and of what doesn’t want to die.

About the Poem

Pablo Neruda’s poem “A Certain Weariness” (original Spanish title: “Cansancio”) is a brief yet profound meditation on the nature of human fatigue—not just physical tiredness, but an existential weariness that creeps in when one confronts the ceaseless demands of life, selfhood, and time. The tone is introspective and slightly melancholic. It is not a dramatic despair but a soft, measured surrender to a moment of emotional depletion. The poem’s mood is quiet, tender, and philosophical—more reflective than sorrowful.

Neruda expresses a feeling that goes beyond ordinary tiredness. It is the soul’s fatigue—the weariness that stems from the need to perform, to act, to continually be someone in the world. There is an underlying longing for retreat, even erasure—just to stop doing and being for a while. This is a subtle nod toward the idea of non-being or nothingness, not as despair but as relief. In being always himself, the speaker feels alienated—trapped in his own name, his own presence, his own continuity. This can be interpreted as a critique of the burdens of self-consciousness and identity.

Pablo Neruda often wrote poems about love, politics, nature, and death, but he also explored solitude and alienation with great lyrical depth. In “A Certain Weariness,” he enters a deeply private space—a confession of burnout and disconnection. It reflects the same existential concerns found in poets like Rilke or even Camus, where consciousness itself becomes exhausting.

“A Certain Weariness” is not merely about being tired—it’s about being overwhelmed by the sheer weight of existing. In it, Neruda captures a universally human moment: when the performance of life feels too heavy, and all one wants is to dissolve for a while into silence, into stillness, into the unknown.

About the Poet

Pablo Neruda, born Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto on July 12, 1904, in Parral, Chile, was one of the most influential and beloved poets of the 20th century. Writing with extraordinary lyricism and political passion, Neruda’s work spanned love, politics, nature, and the human condition—imbued always with a deep sense of sensuality and moral conviction.

Neruda began publishing poetry in his teens, adopting the pen name Pablo Neruda—partly to avoid conflict with his father, who disapproved of his literary ambitions. His breakout collection, Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair(1924), written while he was still a young man, gained international acclaim for its raw intimacy and bold eroticism. From these early romantic verses, his poetry evolved into more politically charged and surrealist work, particularly after his experiences as a diplomat and his travels in Asia and Europe.

A committed Marxist, Neruda served as a Chilean consul in several countries and later became a Senator for the Chilean Communist Party. His political activism—particularly his support of the Spanish Republicans during the Spanish Civil War and his criticism of fascism and imperialism—heavily shaped his later poetry, including the monumental Canto General (1950), a sweeping epic chronicling Latin America’s history and identity.

Despite political persecution that forced him into hiding and exile, Neruda remained a cultural icon in Chile and abroad. In 1971, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, honored as a poet “who brings alive a continent’s destiny and dreams.”

Neruda died on September 23, 1973, just days after the military coup in Chile led by Augusto Pinochet. Though officially attributed to cancer, his death remains the subject of ongoing investigation and speculation due to possible foul play.

Today, Pablo Neruda is remembered not only as a literary giant but as a man who lived at the intersection of beauty and resistance—his words as likely to speak of a lover’s body as of a people’s struggle. His legacy endures in the verses that continue to move hearts across languages and generations.