Monthly Archives: May 2025

The Eternal Flesh of Divine Desire

From the polished marble of ancient statues to the shimmer of modern photography, Greco-Roman gods have been reimagined for centuries as icons of idealized, eroticized male beauty. In myth, their bodies held cosmic power; in art, their nudity has long served as a conduit for expressing desire, divinity, and the human longing for transcendence.

This post explores nude depictions of four major figures—Apollo, Adonis, Dionysus, and Ganymede—through a selection of artworks that span antiquity, the Renaissance, Neoclassicism, and into modern queer photography. These gods persist not merely as symbols of myth but as enduring archetypes of same-sex attraction and aesthetic longing.

Few deities embody beauty like Apollo, the Greek god of light, music, and reason. His idealized, youthful body became the template for masculine perfection across Western art history.

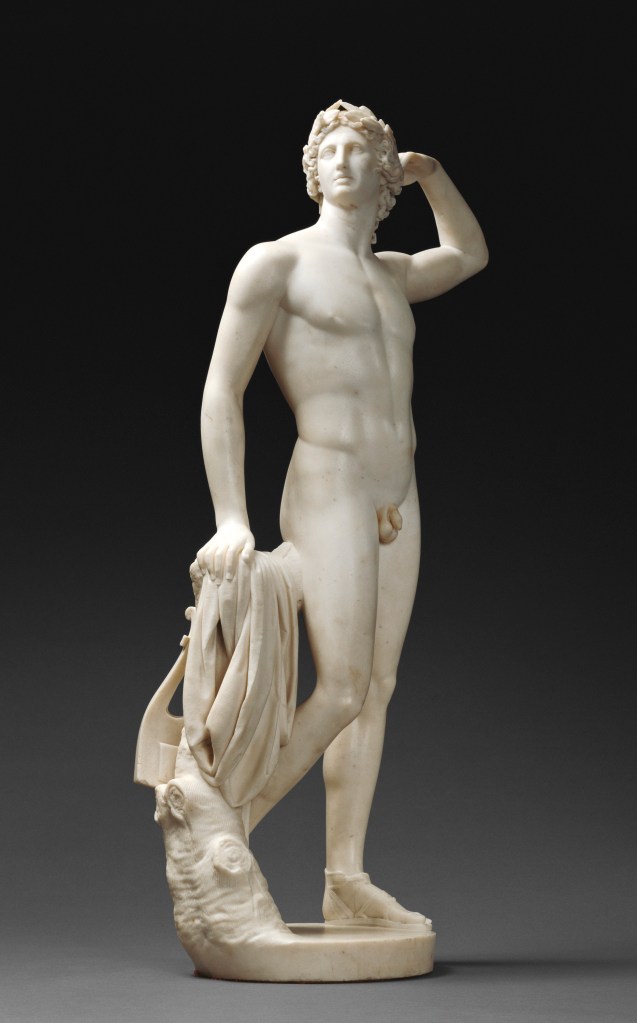

The Apollo Belvedere [above], a Roman copy of a 4th-century BCE Greek bronze, exemplifies this ideal. Standing nude but for a cloak draped over one arm, Apollo’s form is serene, balanced, and timeless.

In the late 18th century, Neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova reinterpreted this ideal in Apollo Crowning Himself [above](1781–1782), depicting the god nude, lifting a laurel wreath with quiet triumph. It is a vision of reason and beauty as divine harmony.

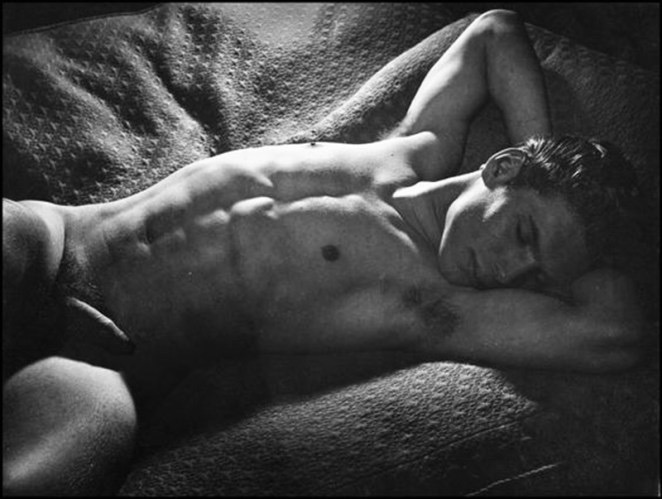

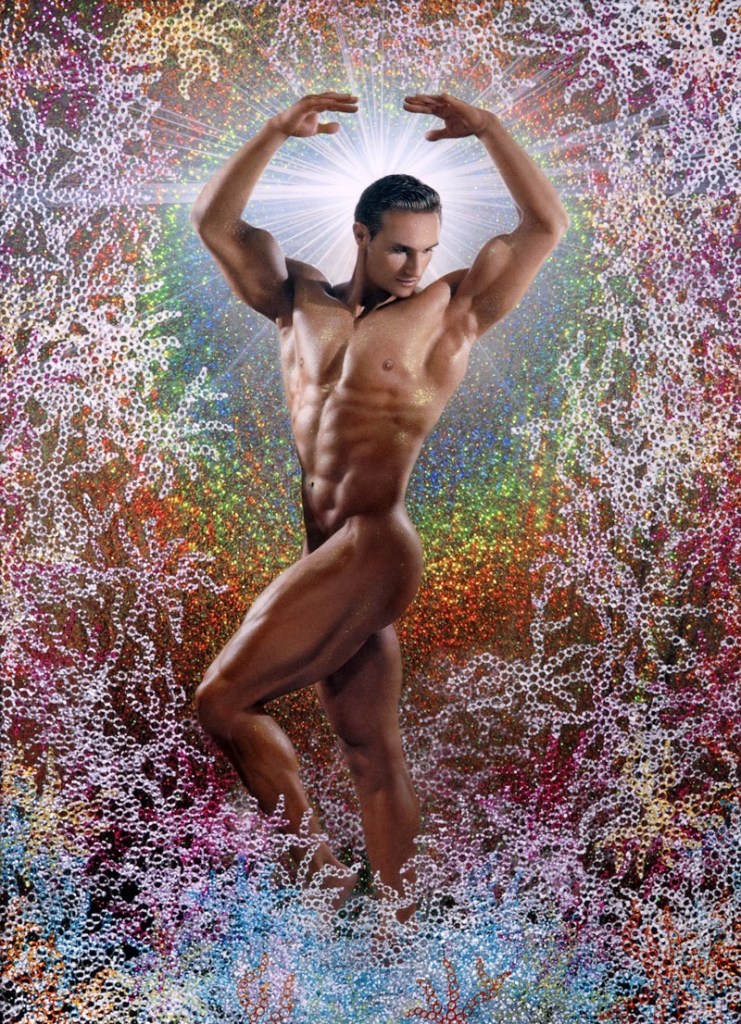

Modern artists have reclaimed Apollo with more intimate and erotic intentions. Photographer Herbert List’s Nap in the Afternoon [above] (1933) portrays a nude young man reclined in soft light, radiating not mythic grandeur but human vulnerability and quiet sensuality. Likewise, Pierre et Gilles’ Apolló [below](2005) transforms the god into a glowing nude queer icon, bathed in gold, sun rays, and self-aware kitsch—modeled by Jean-Christophe Blin with overt erotic charge.

Adonis, loved by both Aphrodite and Persephone, represents ephemeral beauty—the lover who dies young, whose body becomes memory and myth.

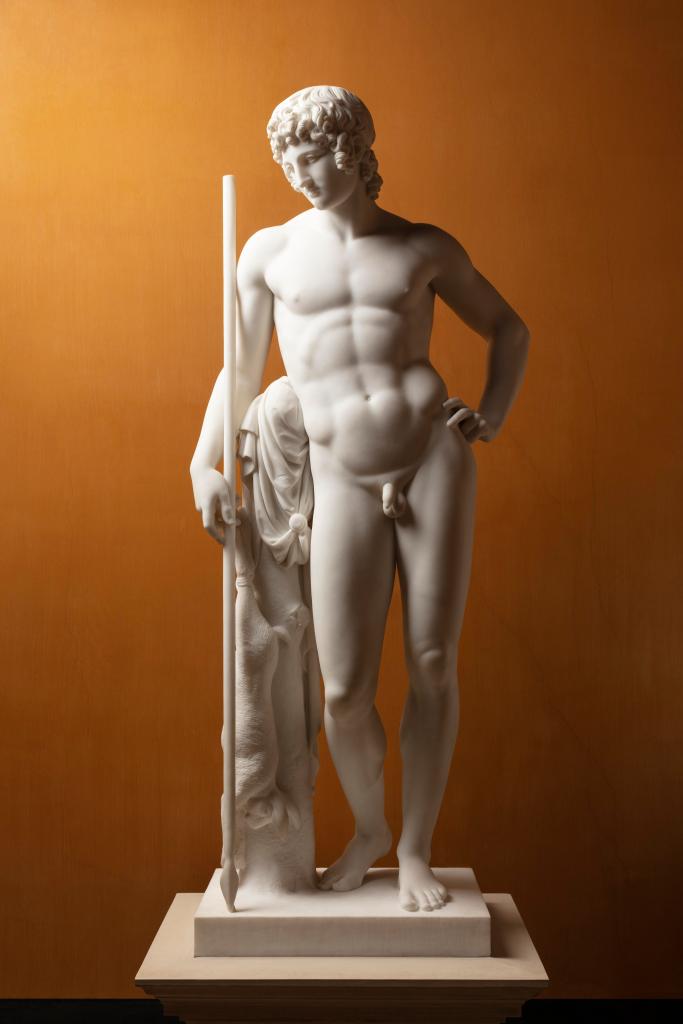

Bertel Thorvaldsen’s Adonis [above] (1808–1832) renders him fully nude and poised with graceful sorrow, a figure both heroic and tender. This tension becomes tragic in Peter Paul Rubens’s Venus Mourning Adonis [below] (1614), where Adonis lies partially nude in Venus’s embrace, his body mourned as much as it was desired.

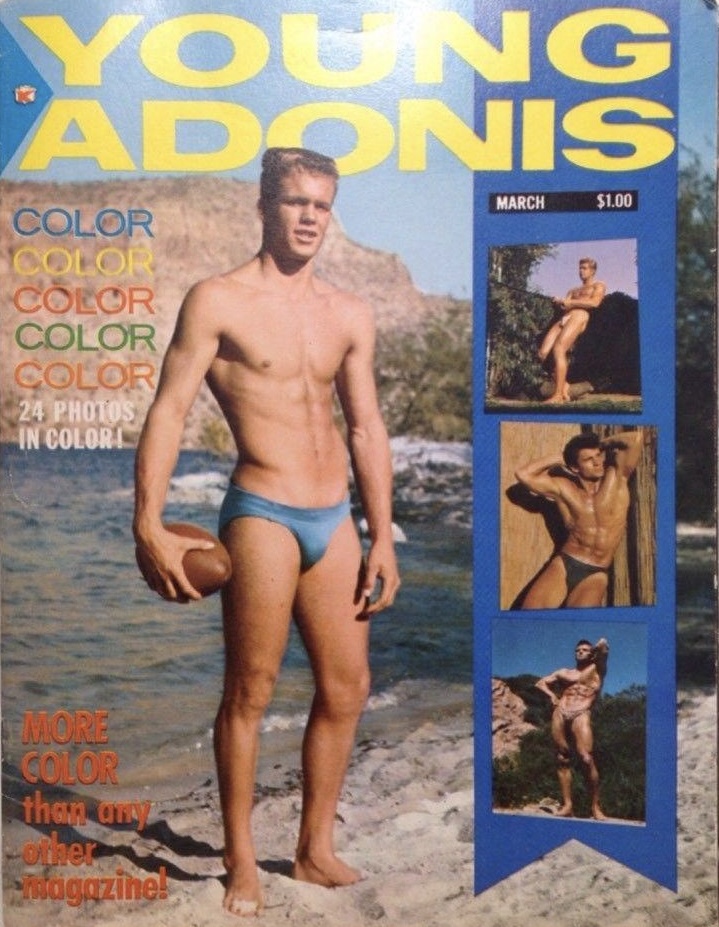

In modernity, Adonis has been reborn as a name for fitness models, physique photography, and pornographic performers. Whether in glossy “Adonis Physique” [below] portfolios or by adult actors adopting the name, these contemporary “gods” continue the legacy of youthful male beauty displayed and consumed—reflecting society’s ongoing obsession with eroticized perfection.

While Apollo embodies clarity and Adonis, fragility, Dionysus represents something wilder—fluid gender, sensual abandon, and ecstatic freedom.

The Ludovisi Dionysus [above] (2nd century CE) captures this duality, showing the god nude and youthful, reclining beside a satyr. His form is less structured than Apollo’s, more languid—inviting the viewer into the pleasures of intoxication and eroticism.

Michelangelo’s Bacchus [above] (1496–1497) expands this image with a staggering, fully nude god offering wine. His body is softly muscled, unsteady, and provocatively unguarded—a subtle challenge to Renaissance masculinity.

In modern queer art and performance, Dionysus is frequently reimagined as a nude figure of androgynous seduction—adorned with ivy, lounging among vessels and male companions. Whether in contemporary photography, drag, or performance art, he embodies liberation from gender, structure, and shame.

Ganymede, the beautiful Trojan prince abducted by Zeus, is mythology’s most overt celebration of male same-sex desire. Ancient Greek art embraced this narrative, often depicting Ganymede nude and pursued by Zeus in eagle form, as on red-figure vases from the 5th century BCE.

Neoclassicism softened the abduction in Bertel Thorvaldsen’s Ganymede and the Eagle [above] (1817). Here, Ganymede stands fully nude, offering a cup to Zeus with serenity and grace. His nudity is not scandalous but dignified, even sacred.

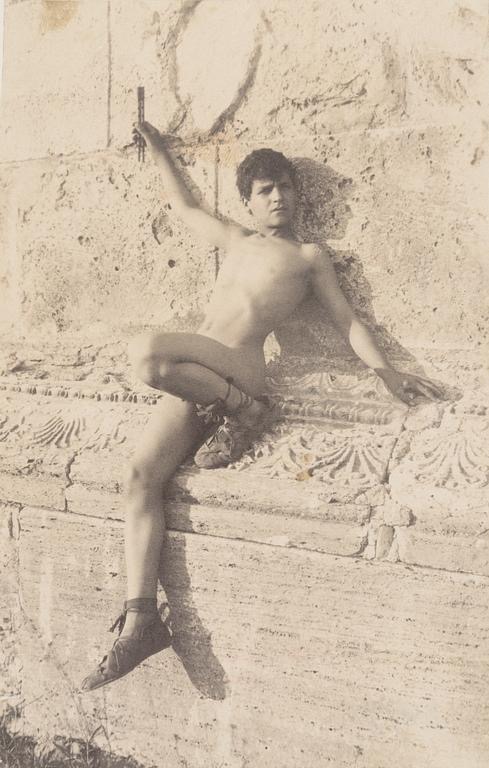

This narrative takes a more intimate turn in Wilhelm von Gloeden’s Ganymede-inspired photographs [above] , taken in Sicily between 1890 and 1910. His nude young models, posed with amphorae or gazing skyward, evoke myth while offering coded homoerotic imagery at a time when queer expression was criminalized. These photographs blend longing, artifice, and resistance—a queer reclamation of myth.

From ancient temples to modern studios, the nude forms of Apollo, Adonis, Dionysus, and Ganymede have served as vessels for beauty, longing, and erotic speculation. Their depictions reveal more than aesthetic ideals; they reflect how cultures across time have understood desire—particularly same-sex desire—not as taboo, but as divine.

These bodies, carved in marble, painted in oils, or captured in silver print, continue to remind us that queer love, and the beauty that awakens it, is older than shame and as enduring as myth.

Love Returned

Love Returned

By Bayard Taylor

He was a boy when first we met;

His eyes were mixed of dew and fire,

And on his candid brow was set

The sweetness of a chaste desire:

But in his veins the pulses beat

Of passion, waiting for its wing,

As ardent veins of summer heat

Throb through the innocence of spring.

As manhood came, his stature grew,

And fiercer burned his restless eyes,

Until I trembled, as he drew

From wedded hearts their young disguise.

Like wind-fed flame his ardor rose,

And brought, like flame, a stormy rain:

In tumult, sweeter than repose,

He tossed the souls of joy and pain.

So many years of absence change!

I knew him not when he returned:

His step was slow, his brow was strange,

His quiet eye no longer burned.

When at my heart I heard his knock,

No voice within his right confessed:

I could not venture to unlock

Its chambers to an alien guest.

Then, at the threshold, spent and worn

With fruitless travel, down he lay:

And I beheld the gleams of morn

On his reviving beauty play.

I knelt, and kissed his holy lips,

I washed his feet with pious care;

And from my life the long eclipse

Drew off; and left his sunshine there.

He burns no more with youthful fire;

He melts no more in foolish tears;

Serene and sweet, his eyes inspire

The steady faith of balanced years.

His folded wings no longer thrill,

But in some peaceful flight of prayer:

He nestles in my heart so still,

I scarcely feel his presence there.

O Love, that stern probation o’er,

Thy calmer blessing is secure!

Thy beauteous feet shall stray no more,

Thy peace and patience shall endure!

The lightest wind deflowers the rose,

The rainbow with the sun departs,

But thou art centred in repose,

And rooted in my heart of hearts!

About the Poem

Bayard Taylor is not a household name today, but in the 19th century, he was known as a celebrated American poet, travel writer, and diplomat. A close contemporary of figures like Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson, Taylor’s work was steeped in romantic idealism, emotional intensity, and the mystique of distant lands. One of his lesser-known but deeply resonant poems, “Love Returned,” offers a quiet but powerful meditation on lost love.

At first glance, “Love Returned” seems to be about an emotionally bruised speaker reckoning with the unexpected return of a former beloved. The title suggests something joyful, even redemptive. And yet, the tone of the poem is anything but triumphant. Instead of welcoming love back with open arms, the speaker responds with hesitation, guardedness, and sorrow. There’s a clear sense that too much time has passed, too much pain has been endured. The love that once flourished now feels shadowed by distance and distrust.

Lines such as:

“Thou com’st too late, O love of mine…”

reveal the speaker’s reluctance to embrace this returning affection. We sense a deep internal struggle: the heart that once yearned is now tempered by hard-won wisdom and past wounds. Love may return, but the damage of its absence lingers. The emotional register here is raw and sincere, placing it squarely among the more moving poetic treatments of love’s ambivalence and timing.

In “Love Returned,” the use of abstract, universal terms like “Love,” “thou,” and “mine” allows readers of any gender or orientation to find themselves in the speaker’s position. But for LGBTQ readers—particularly those who have experienced the painful dynamics of love delayed, denied, or hidden—the emotional undercurrents may feel particularly resonant. The poem evokes that aching space between longing and fulfillment, a space many queer people have inhabited at some point in their lives.

Moreover, the speaker’s refusal to immediately accept the returning love is layered with meaning. It’s not just about betrayal or abandonment. It might also speak to the fear of being hurt again, of trusting love that once had to be hidden, or of reckoning with the societal forces that prevented it from being fully realized the first time. It is a deeply human moment, but also one that echoes the specific emotional terrain of queer lives lived in secrecy.

About the Poet

Bayard Taylor (1825–1878) was a prolific American poet, novelist, journalist, travel writer, and diplomat. Born in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, Taylor demonstrated a precocious talent for language and literature from a young age. He began publishing poetry in his teens and soon embarked on the first of many extensive journeys abroad—travels that would inspire a series of widely read books chronicling his experiences in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. Taylor became a household name in mid-19th century America for his vivid travel writing and poetry, including the popular Views Afoot (1846) and Poems of the Orient (1854). He served as a diplomat in Russia and later as U.S. Minister to Prussia (now part of Germany), where he died in 1878 at the age of 53.

While Taylor married and led a respected public life, modern scholars have noted homoerotic undertones in much of his poetry and correspondence, suggesting that Taylor experienced same-sex attraction, particularly in his youth, but he lived in a time when open expressions of same-sex love were dangerous—legally, socially, and professionally. His early poems often feature idealized male figures and deep emotional bonds between men, framed in ways that were common among queer writers of the 19th century who had to navigate a society that criminalized or pathologized homosexuality. Like many queer writers of the 19th century, Taylor often employed gender-neutral language, making it possible for his expressions of love to be read in multiple ways. This ambiguity was not just a poetic device; it was a shield, allowing intimacy and affection to pass under the radar of a society that punished queer expression.

Taylor’s personal letters and early poetry hint at a rich and complex emotional world in which same-sex desire played a significant role. Though he later married and maintained a public heterosexual persona, he had deep emotional bonds with men—some of which appear to have crossed into romantic or erotic territory. Scholars have identified several of Taylor’s poems, including “To a Young Soldier” and several of his Eastern-themed verses, as part of a larger tradition of 19th-century queer poetics—works that expressed forbidden feelings through coded language, aesthetic distancing, and allegory.

Taylor’s relationships with male friends—intense, affectionate, and sometimes suggestively romantic—reflect a pattern familiar to LGBTQ+ historians: a life of coded expression, emotional sublimation, and poetic longing. While he did not (and likely could not) openly identify as queer in his time, Taylor’s body of work contains a rich undercurrent of queer sensibility, especially in poems like “Love Returned” and “To a Young Soldier.” Today, Bayard Taylor is recognized not only as a pioneering American literary voice but also as an important figure in early queer literary history, whose writings offer a window into the inner lives of men who loved other men in an era of silence.

A Staycation with Style

With the exception of this Thursday and next, I’m on a two-week break—finally using up my remaining vacation days before the new fiscal year begins on June 1. Unless travel money miraculously drops into my bank account, this will be a staycation. And honestly, I’m okay with that.

My only real plans for the next couple of weeks are simple ones: I’ll be keeping up with my Monday, Wednesday, and Friday workout sessions with my trainer, and I’ve got dinner plans with a good friend on Friday night. That dinner, in particular, is something I’ve really been looking forward to.

We’re going to the only place around here that serves a wine I truly enjoy: Henri Perrusset Mâcon-Villages Chardonnay, from Burgundy, France. Now, I don’t drink often—maybe the occasional margarita, a vodka cranberry, or a hard cider—but this chardonnay is something special. It’s a bit of an exception for me, since I usually prefer sauvignon blanc or pinot grigio, typically French or Italian, with a particular fondness for wines from the Loire Valley.

I’m sure the wine aficionados reading this might cringe at my taste, but I gravitate toward crisp, dry white wines. I’ve never really learned the proper terminology to describe wine, but every time I look up the ones I like, they all seem to fall under that “dry and crisp” category.

The restaurant’s food is good, though maybe not exceptional. I usually order the lobster and shrimp scampi—it’s solid, even if lobster isn’t my favorite seafood. (Let’s be honest, sometimes it feels like restaurants throw lobster into a dish just so they can hike up the price.) What really makes the meal, though, is dessert. Their flourless chocolate cake is rich, dense, and downright decadent. And the cheesecake? Also worth the calories.

I’m also surprisingly looking forward to my workouts. That’s not a sentence I ever expected to write, but here we are. My trainer has found the right balance—he doesn’t push me too hard, knowing I haven’t seriously worked out in years, but he still challenges me just enough. It’s early days, but we’re making real progress. It feels good.

And while food and wine are lovely perks, what I’m most excited about is the simple pleasure of getting dressed up and heading out. I don’t often get the chance to really put together an outfit and enjoy an evening out, so Friday night will be a treat. Good wine, decent food, indulgent dessert, and—most importantly—a great friend whose company I know I’ll thoroughly enjoy.

Staycation or not, it’s shaping up to be a good couple of weeks.

We Are All God’s Children

For God has consigned all to disobedience, that he may have mercy on all. Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!

— Romans 11:32-33

Sometimes I wonder if Paul, in writing Romans 9–11, was feeling what many of us in the LGBTQ+ Christian community have felt: the ache of being part of a people who seem to have rejected something essential and life-giving. For Paul, it was watching his beloved Jewish community turn away from the gospel of Christ (Romans 9:1–3). For me—and for so many of us—it’s standing in churches that reject us while clinging to a gospel we know in our bones is about mercy, love, and inclusion. Romans 10:12–13 says, “For there is no difference between Jew and Gentile—the same Lord is Lord of all and richly blesses all who call on him, for, ‘Everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.’” In Galatians 3:28, Paul tells us, “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

Paul’s conclusion in Romans 11 is not one of despair, but of wonder. After wrestling with rejection, exclusion, and the mysteries of God’s plan, in Romans 11:32 he writes “For God has consigned all to disobedience, that he may have mercy on all.”

We know something about rejection. We’ve heard the sermons, felt the silence, watched doors close. Isaiah 56:3-5 says:

Let no foreigner who is bound to the Lord say,

“The Lord will surely exclude me from his people.”

And let no eunuch complain,

“I am only a dry tree.”For this is what the Lord says:

“To the eunuchs who keep my Sabbaths,

who choose what pleases me

and hold fast to my covenant—

to them I will give within my temple and its walls

a memorial and a name

better than sons and daughters;

I will give them an everlasting name

that will endure forever.

Some of us have been told we must change to be loved by God—when all along, we were already held in that love. Romans 8:38–39 says, “For I am convinced that neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord.” And yet despite the rejections of others… we stayed. We sang the hymns. We read Scripture with reverence. We wept and prayed and kept believing that God’s mercy is bigger than the world’s fear. Micah 6:8 says, “He has shown you, O mortal, what is good. And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.” Jesus rebuked those who have put up walls of exclusion. In Matthew 23:23 He says, “Woe to you, teachers of the law and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You give a tenth of your spices—mint, dill and cumin. But you have neglected the more important matters of the law—justice, mercy and faithfulness. You should have practiced the latter, without neglecting the former.”

Romans 11 is a reminder: rejection is not the end of the story. Romans 11:1–2 says, “I ask then: Did God reject his people? By no means! I am an Israelite myself, a descendant of Abraham, from the tribe of Benjamin. God did not reject his people, whom he foreknew. Don’t you know what Scripture says in the passage about Elijah—how he appealed to God against Israel.” (1 Kings 19:10-18) God is not finished with Israel, and God is certainly not finished with us. God’s plan was never about gatekeeping, never about purity tests or theological litmus strips. It was—and is—about mercy breaking into the human mess. Paul says in Romans 5:8, “But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us,” and Hosea 6:6 says, “For I desire mercy, not sacrifice, and acknowledgment of God rather than burnt offerings.”

Paul calls this a mystery. In Romans 11:25, he says, “I do not want you to be ignorant of this mystery, brothers and sisters, so that you may not be conceited: Israel has experienced a hardening in part until the full number of the Gentiles has come in.” And it is. It’s a mystery that the very people who were told they didn’t belong—Gentiles, outcasts, eunuchs, queers, sinners—are the ones Christ drew near to (Luke 7:36–50; John 4:7–29; Acts 8:26–39). It’s a mystery that God would use rejection to teach the church mercy. That even now, in a world and church still wrestling with whom to embrace, God is quietly gathering all of us in. (Ephesians 2:13–19) Jesus tells the Pharisees in John 10:16, “I have other sheep that are not of this sheep pen. I must bring them also. They too will listen to my voice, and there shall be one flock and one shepherd.”

We do not need to prove our worth to God. In Titus 3:4–7, Paul write to Titus and says, “But when the kindness and love of God our Savior appeared, he saved us, not because of righteous things we had done, but because of his mercy. He saved us through the washing of rebirth and renewal by the Holy Spirit, whom he poured out on us generously through Jesus Christ our Savior, so that, having been justified by his grace, we might become heirs having the hope of eternal life” We are not spiritual refugees in someone else’s kingdom. We are already part of the body of Christ—beloved, chosen, and called. Romans 12:4–5 says, “For just as each of us has one body with many members, and these members do not all have the same function, so in Christ we, though many, form one body, and each member belongs to all the others,” and Colossians 3:12 says, “Therefore, as God’s chosen people, holy and dearly loved, clothe yourselves with compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness and patience.”

Romans 11 doesn’t end in doctrine. It ends in doxology—a song of praise.

Oh, the depth of the riches of the wisdom and knowledge of God!

How unsearchable his judgments,

and his paths beyond tracing out!

“Who has known the mind of the Lord?

Or who has been his counselor?”

“Who has ever given to God,

that God should repay them?”

For from him and through him and for him are all things.

To him be the glory forever! Amen. (Romans 11:33-36)

That is where we live too: in that mysterious, radiant space between pain and praise. We have seen rejection, yes. But we’ve also seen what mercy can do. We’ve tasted the unsearchable depths of God’s wisdom and kindness. And we believe—despite it all—that mercy is coming for everyone. Remember Paul’s question in Romans 2:4, “Or do you show contempt for the riches of his kindness, forbearance and patience, not realizing that God’s kindness is intended to lead you to repentance?” In 1 Timothy 2:3–4, Paul tells Timothy, “This is good, and pleases God our Savior, who wants all people to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth.”

God is merciful. As LGBTQ+ Christians have known the sting of rejection, and we have heard his voice calling us beloved. We should thank Him for His mystery. We should thank God for His patience, and for His mercy including all of us, even when others do not. His Word can guide us to live in His mercy and help us to share it with others. God is not done yet—not with the church, not with this world, and, most certainly, not with us.

Moment of Zen: Cooper Koch

You may have seen that Cooper Koch is the newest male model for Calvin Klein.

Cooper, who is gay, has a twin brother Payton, who’s just as swoon-worthy (and also gay). Payton prefers to remain behind the camera as a film editor. He received an Emmy nomination for his editing of Only Murders in the Building.