Song of Myself, XI

by Walt Whitman

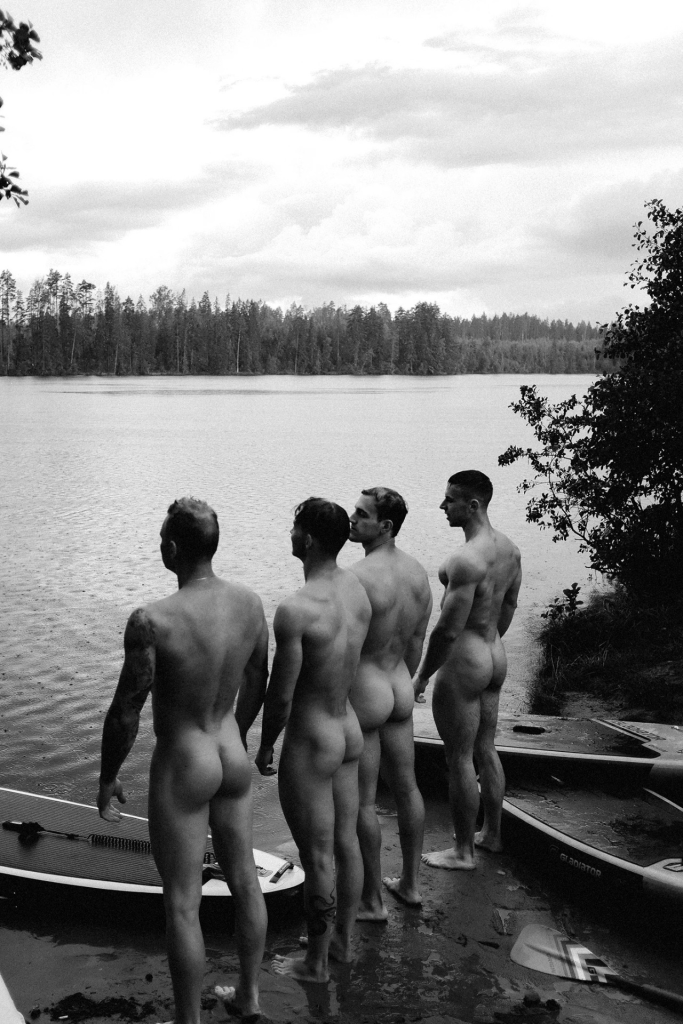

Twenty-eight young men bathe by the shore,

Twenty-eight young men and all so friendly;

Twenty-eight years of womanly life and all so lonesome.

She owns the fine house by the rise of the bank,

She hides handsome and richly drest aft the blinds of the window.

Which of the young men does she like the best?

Ah the homeliest of them is beautiful to her.

Where are you off to, lady? for I see you,

You splash in the water there, yet stay stock still in your room.

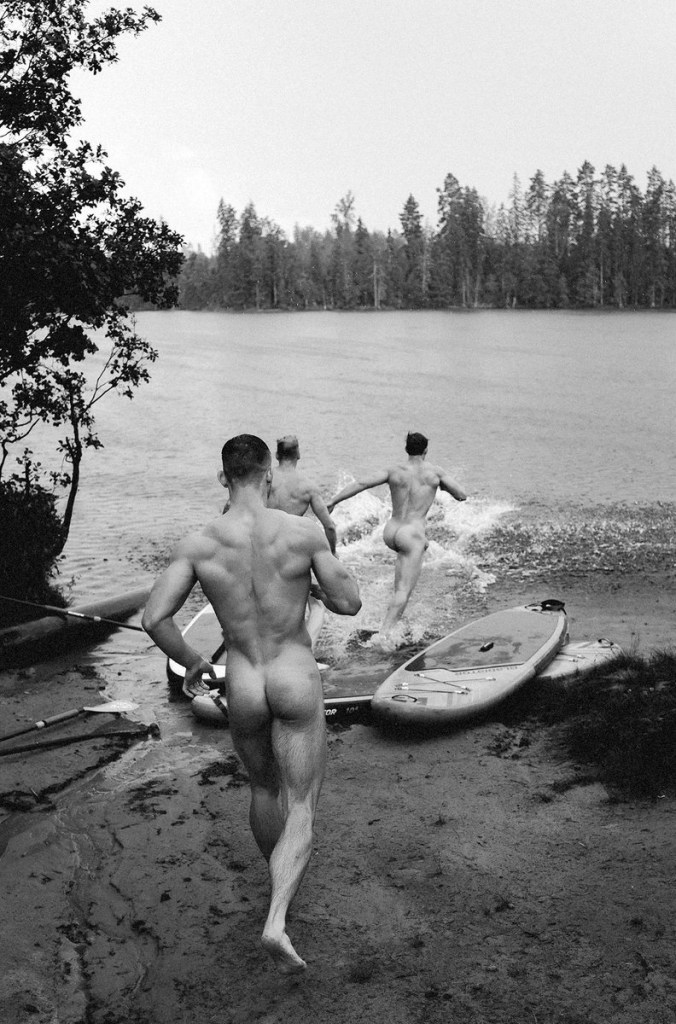

Dancing and laughing along the beach came the twenty-ninth bather,

The rest did not see her, but she saw them and loved them.

The beards of the young men glistened with wet, it ran from their long hair,

Little streams passed all over their bodies.

An unseen hand also passed over their bodies,

It descended tremblingly from their temples and ribs.

The young men float on their backs, their white bellies bulge to the sun, they do not ask who seizes fast to them,

They do not know who puffs and declines with pendant and bending arch,

They do not think whom they souse with spray.

About the Poem

This section of Leaves of Grass is one of Walt Whitman’s most quietly radical explorations of desire, longing, and the power of imagination. Twenty-eight young men bathe naked together in the water, carefree and unselfconscious, while a woman of the same age watches from the privacy of her home. She is physically separated from them—clothed, indoors, alone—yet in her imagination she becomes the “twenty-ninth bather,” joining their laughter and movement, touching and being touched. The men never see her; the encounter exists entirely within her longing.

Whitman presents this imagined intimacy as emotionally and sensually real, refusing to diminish it simply because it is unacted. There is no punishment for desire here, no moral correction. Wanting, especially wanting that cannot be fulfilled, is treated as a fundamental human experience rather than a failing. The poem honors the interior life as a space where longing has its own truth and legitimacy.

For 19th-century readers, this treatment of desire was deeply unsettling. The poem lingers on naked male bodies without euphemism, grants a woman an active erotic imagination, and treats sexual fantasy as natural rather than sinful. Victorian literary culture demanded modesty, restraint, and silence—particularly from women—but Whitman offers none of those reassurances. Instead, he insists on the holiness of the body and the legitimacy of erotic thought.

At the same time, the poem’s gaze dwells unmistakably on male physicality and communal intimacy: bodies floating together, bellies turned toward the sun, touch passing freely among them. This focus aligns with Whitman’s broader treatment of male-male closeness throughout Song of Myself, where affection between men is often physical, tender, and spiritually charged. Although framed through a woman’s perspective, the poem participates in Whitman’s larger project of celebrating bodily connection beyond conventional boundaries.

Read this way, the woman’s presence can feel almost like a veil—one that allows Whitman to explore erotic attention to male bodies and shared sensuality while navigating the social constraints of his time. Ultimately, the poem becomes less about voyeurism and more about exclusion and yearning: the ache to cross boundaries, to belong to a world of unguarded bodies and mutual touch, and to claim desire itself as something worthy of recognition and song.

About the Poet

Walt Whitman (1819–1892) reshaped American poetry by rejecting formal verse and embracing a bold, expansive free style that celebrated the self, the body, and the collective human experience.

With Leaves of Grass, Whitman insisted that:

- The body is sacred

- Desire is not separate from spirituality

- Love—especially between men—deserves poetic dignity

Though he never publicly named his sexuality, Whitman’s poetry has long been recognized as foundational to queer literary history. His work insists on the holiness of physicality and the legitimacy of desires that society prefers to hide.

Whitman’s enduring challenge to readers is simple and radical: to see the human body, in all its longing and beauty, as worthy of love and song.

Thank you for commenting. I always want to know what you have to say. However, I have a few rules: 1. Always be kind and considerate to others. 2. Do not degrade other people's way of thinking. 3. I have the right to refuse or remove any comment I deem inappropriate. 4. If you comment on a post that was published over 14 days ago, it will not post immediately. Those comments are set for moderation. If it doesn't break the above rules, it will post.