From the marble gods of antiquity to the chiaroscuro of contemporary fine art photography, the male nude has long served as a canvas for ideals—beauty, heroism, eroticism, even vulnerability. While fashions shift and aesthetics evolve, certain poses recur again and again across centuries, connecting ancient sculptors with modern photographers, and Renaissance artists with queer creators exploring body and identity. These poses are not random; they are visual codes, passed down like a secret language. Below are ten of the most iconic, from the classical to the contemporary.

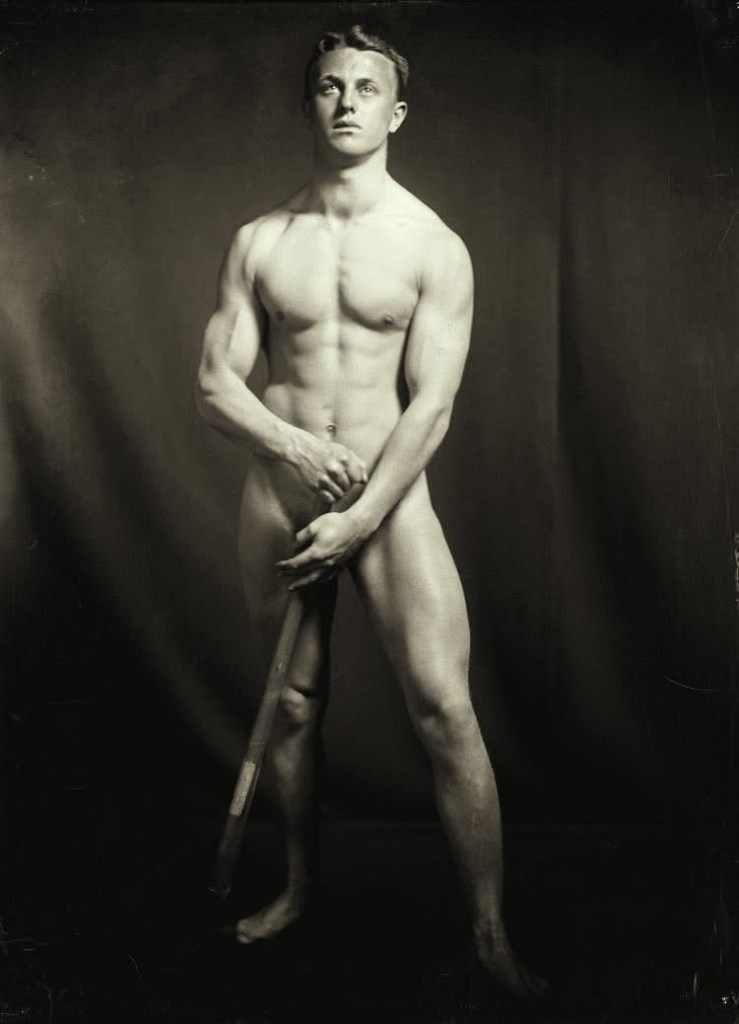

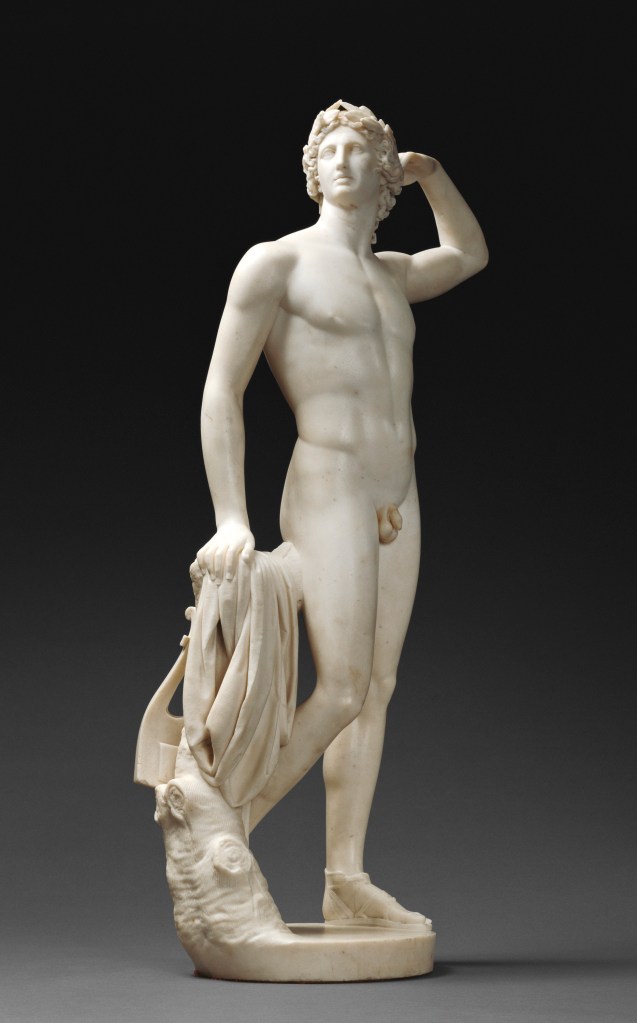

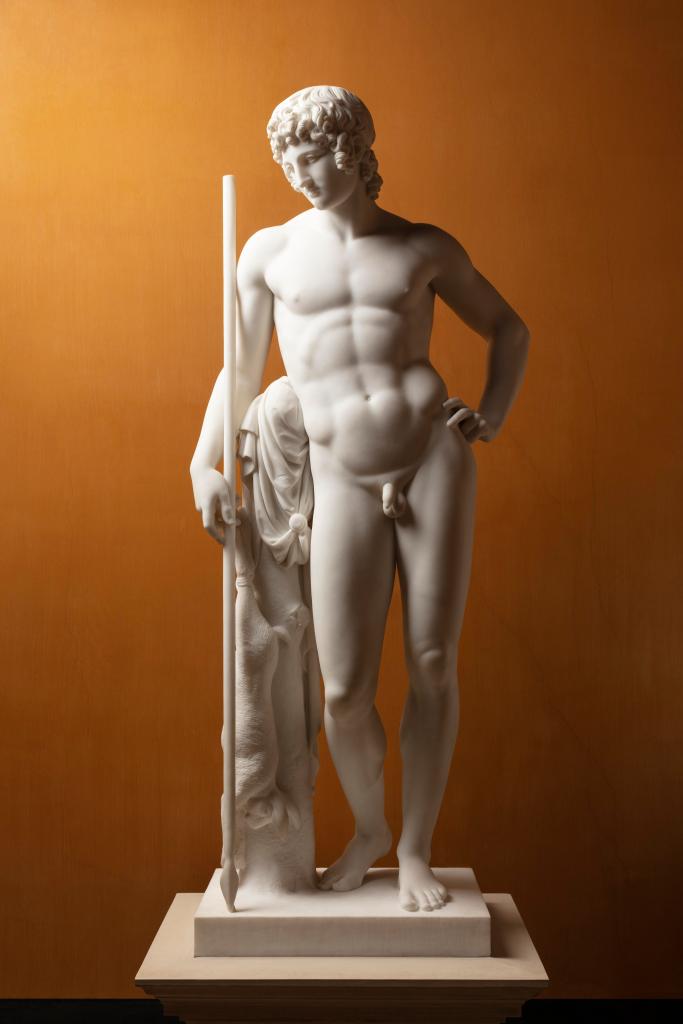

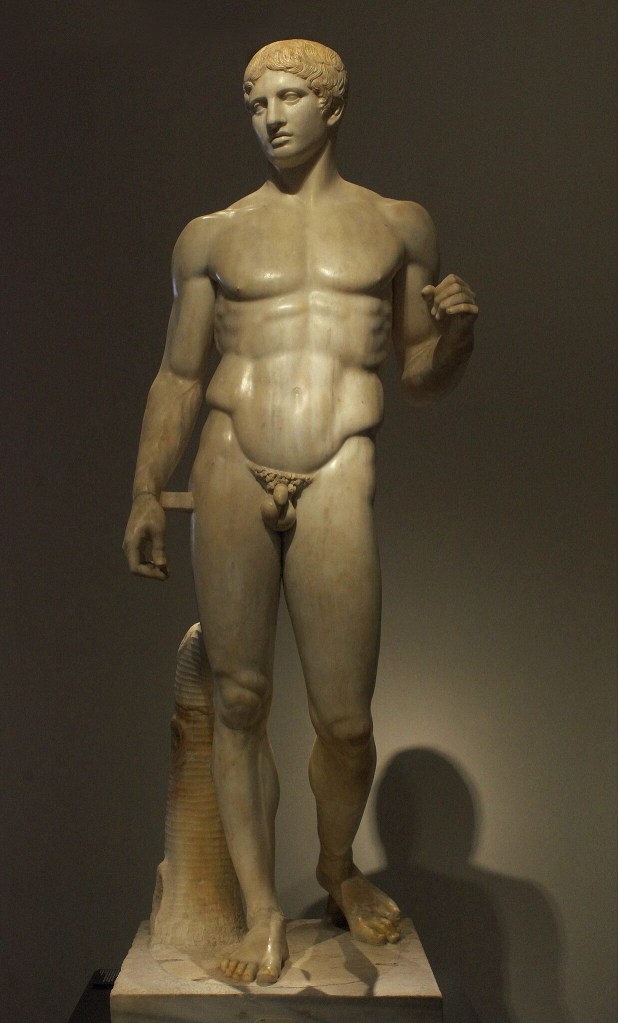

Contrapposto — The Classical Stand

The contrapposto is perhaps the most recognizable pose in Western art. One leg bears weight while the other relaxes, creating a subtle S-curve in the spine and a naturalistic opposition of shoulders and hips. It suggests calm confidence, inner balance, and effortless beauty—a divine masculinity grounded in the human form. This pose remains a standard in fine art photography, particularly in black-and-white portraiture where tension and repose dance together in the frame.

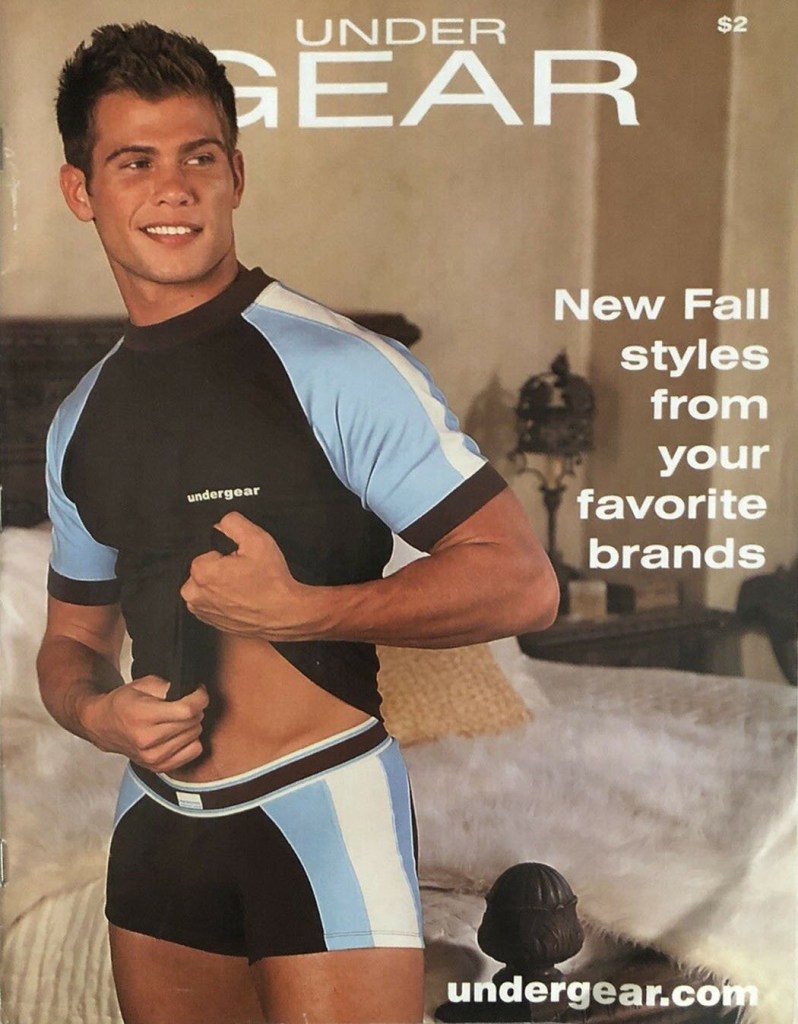

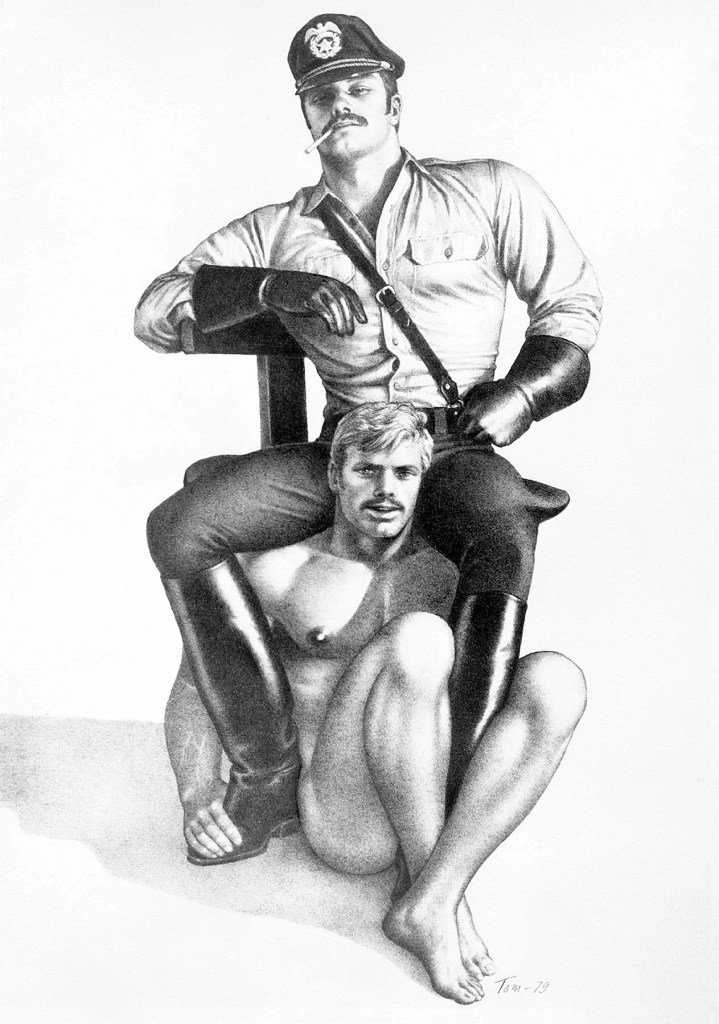

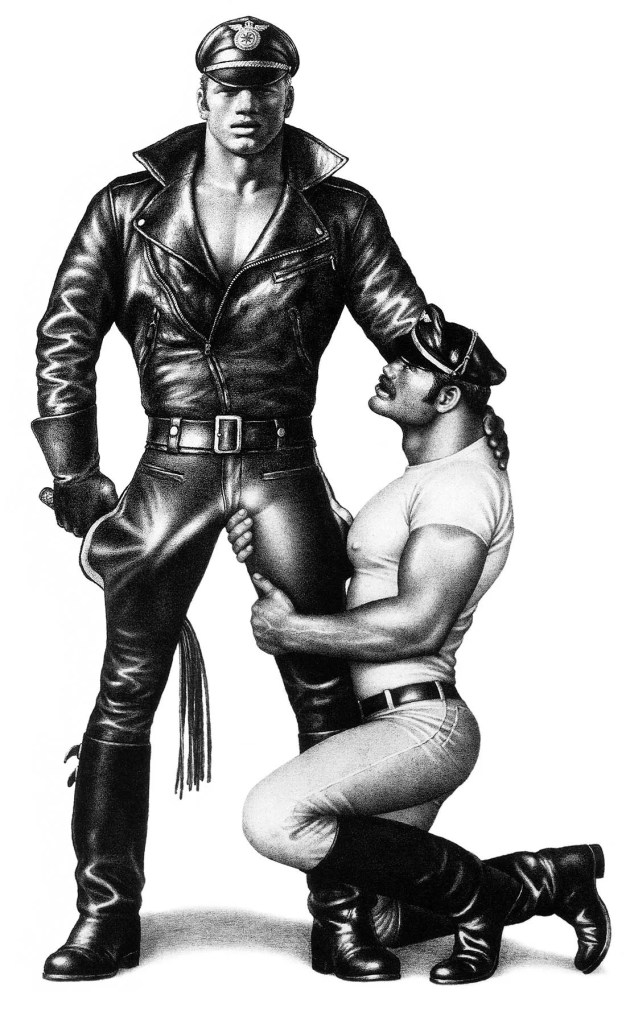

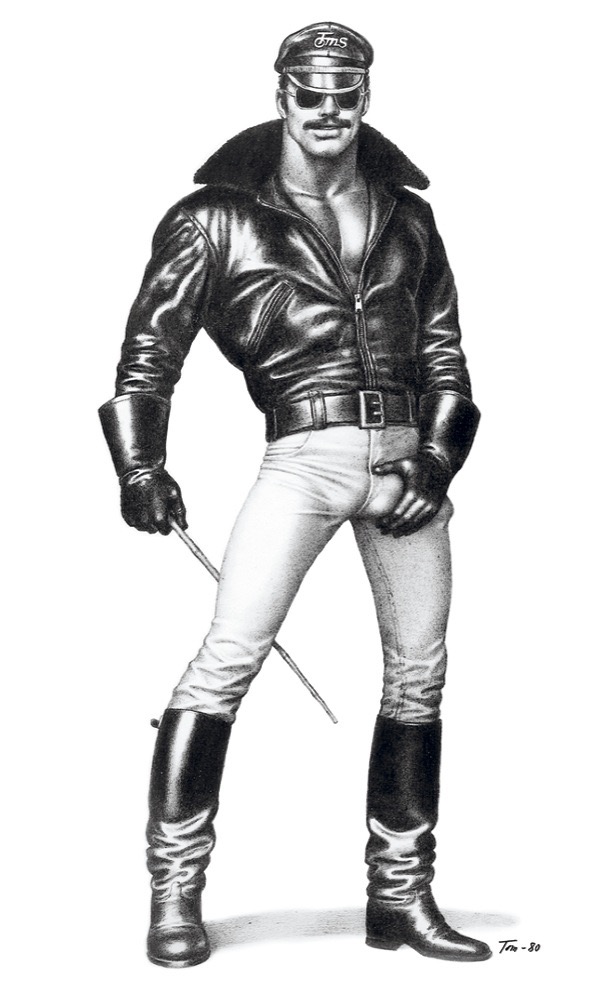

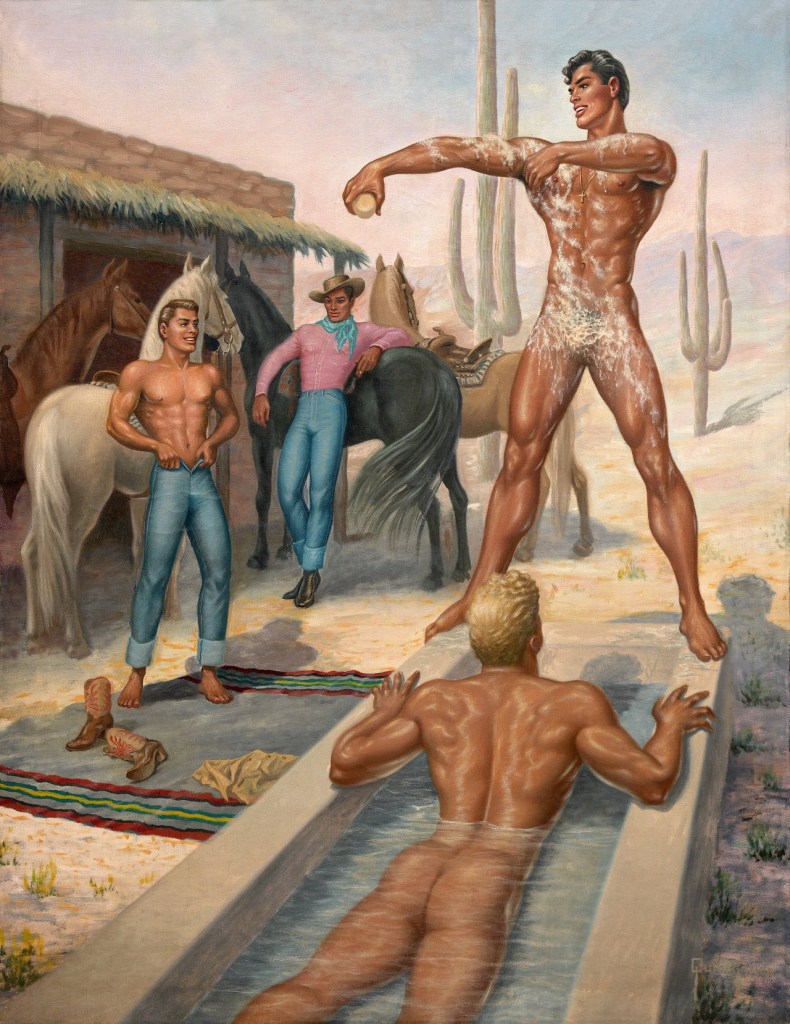

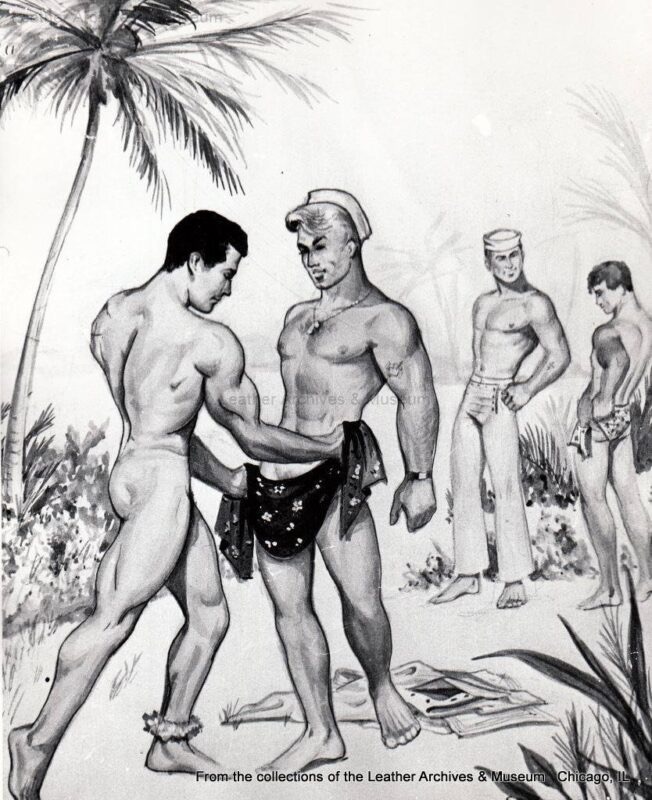

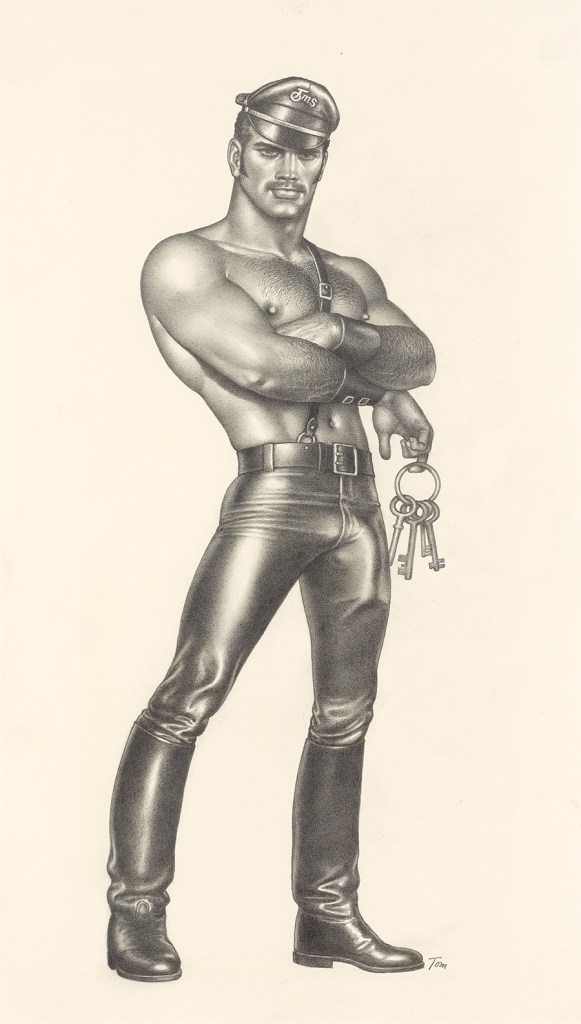

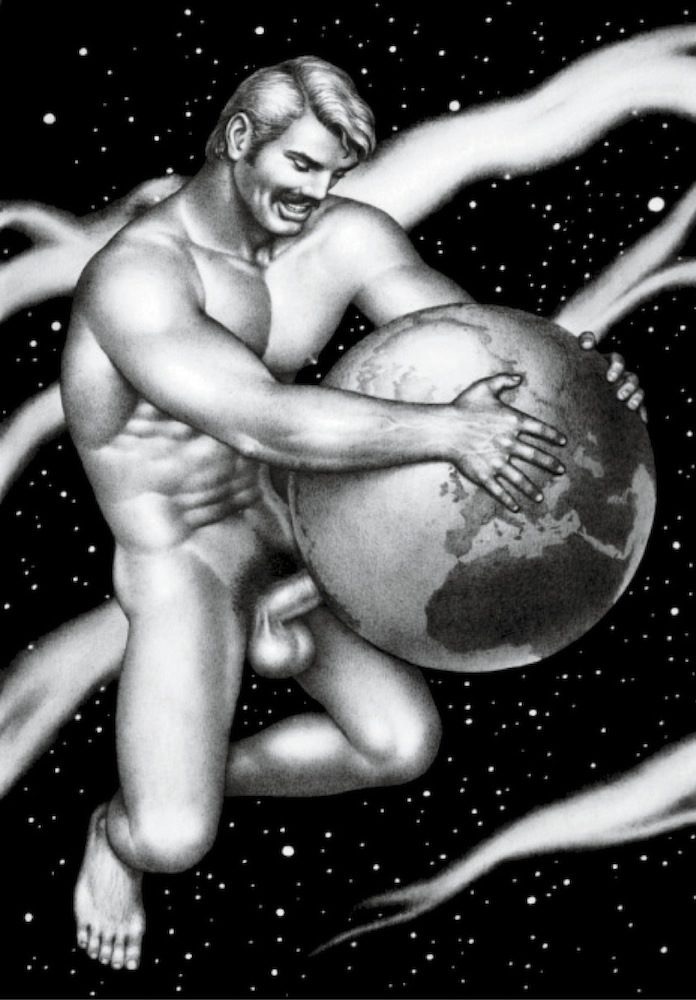

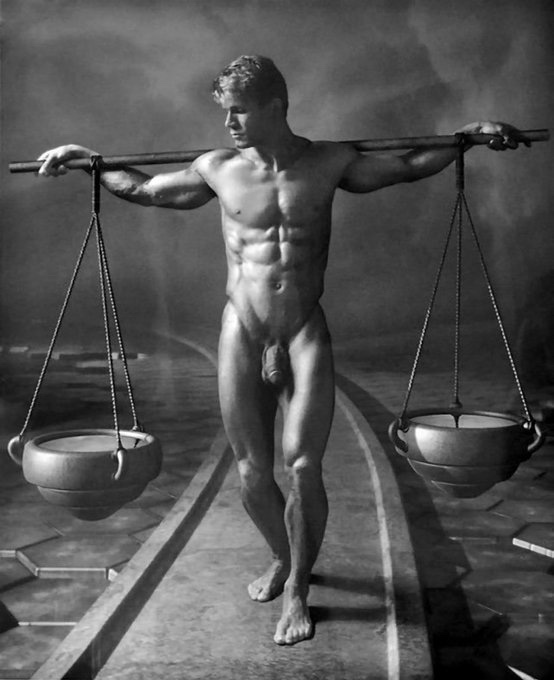

The Heroic Nude

This pose stretches the body into exaggerated musculature—shoulders squared, stance wide, genitals often prominently displayed. In mythological sculptures and athletic statues, the heroic nude expressed power without armor, valor without shame. Modern echoes appear in Bruce Weber’s Calvin Klein ads or Tom of Finland’s hyper-masculine pinups, though with more erotic charge and often a wink of camp.

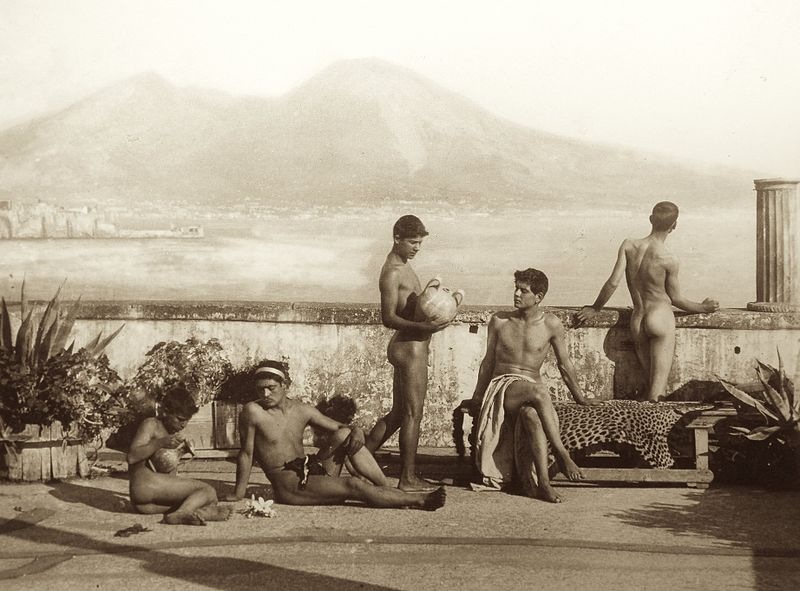

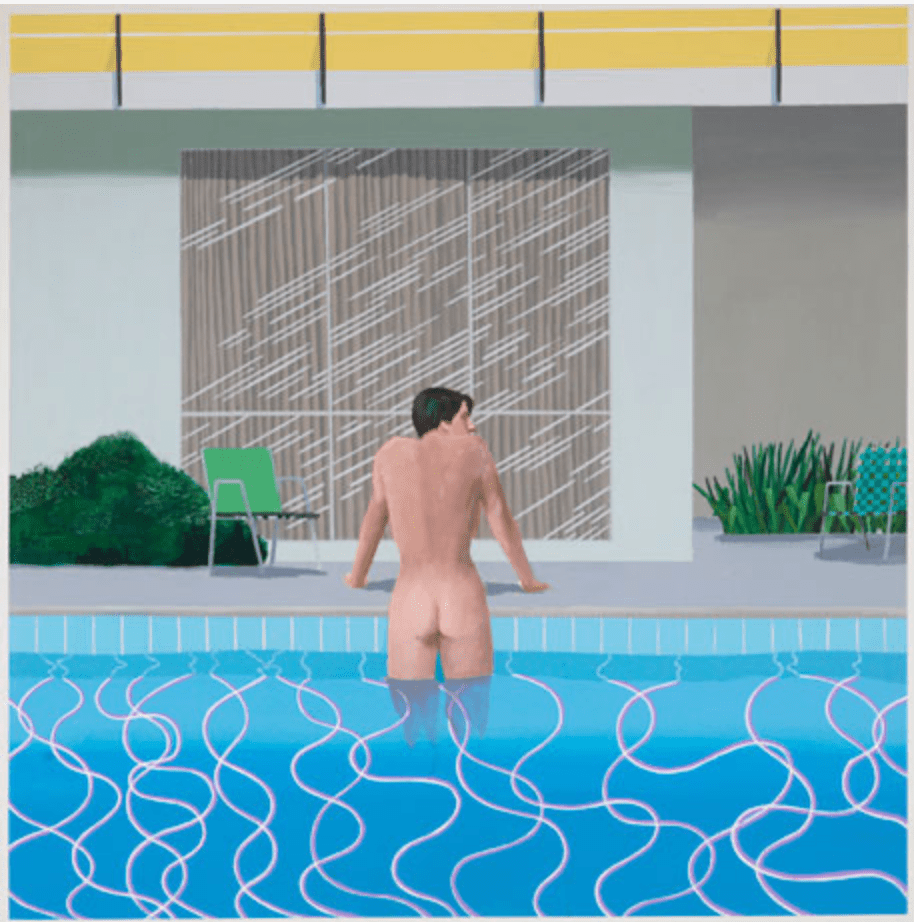

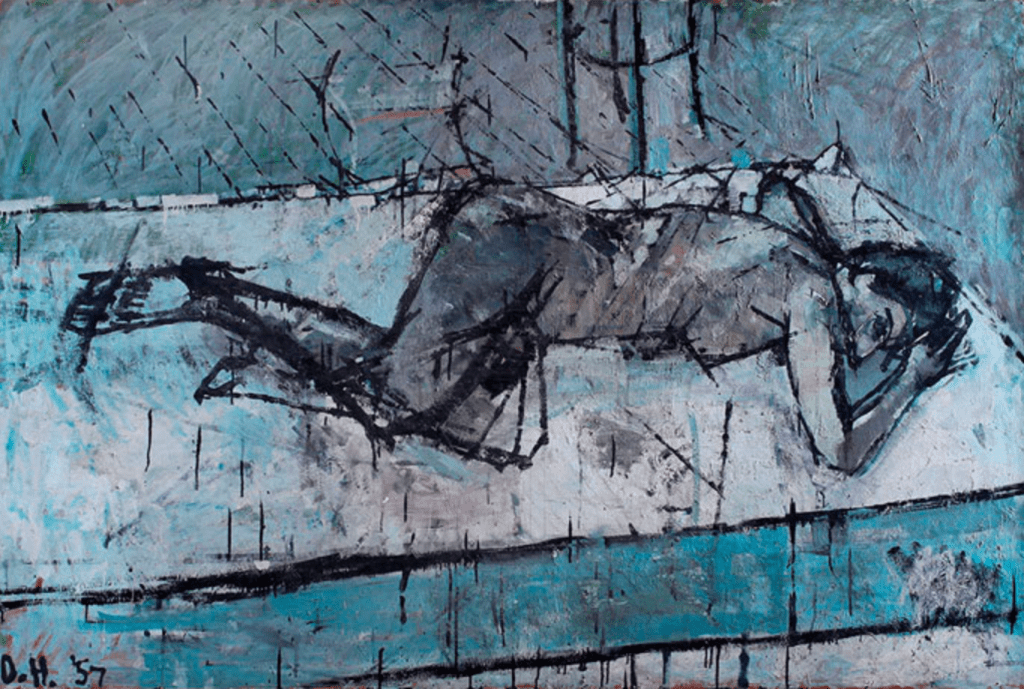

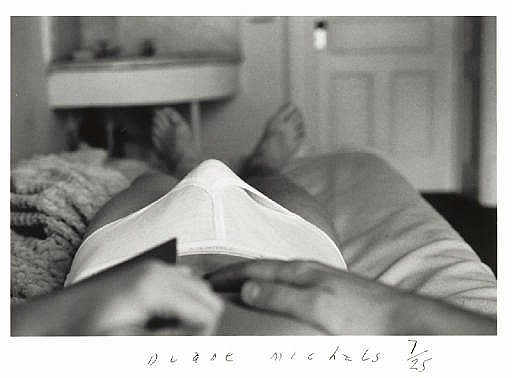

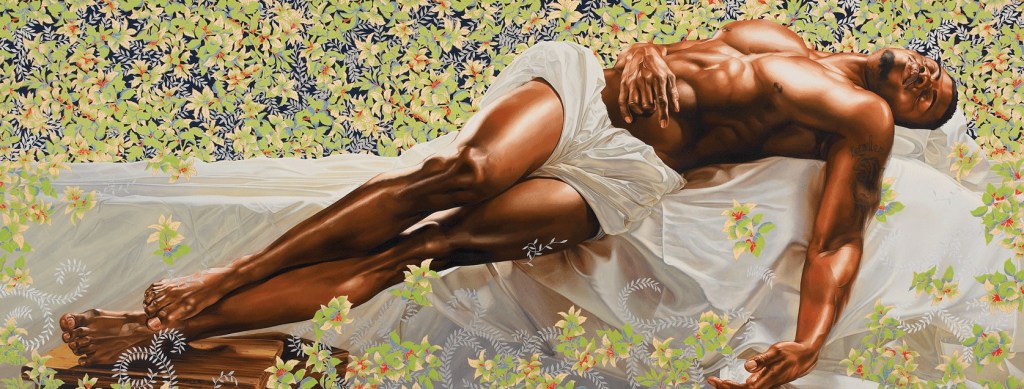

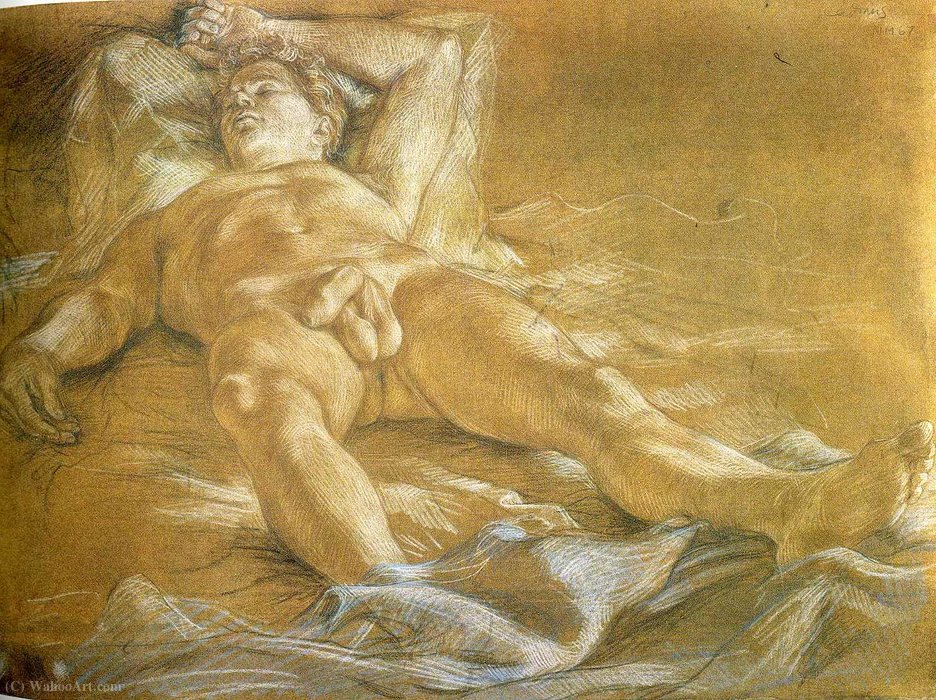

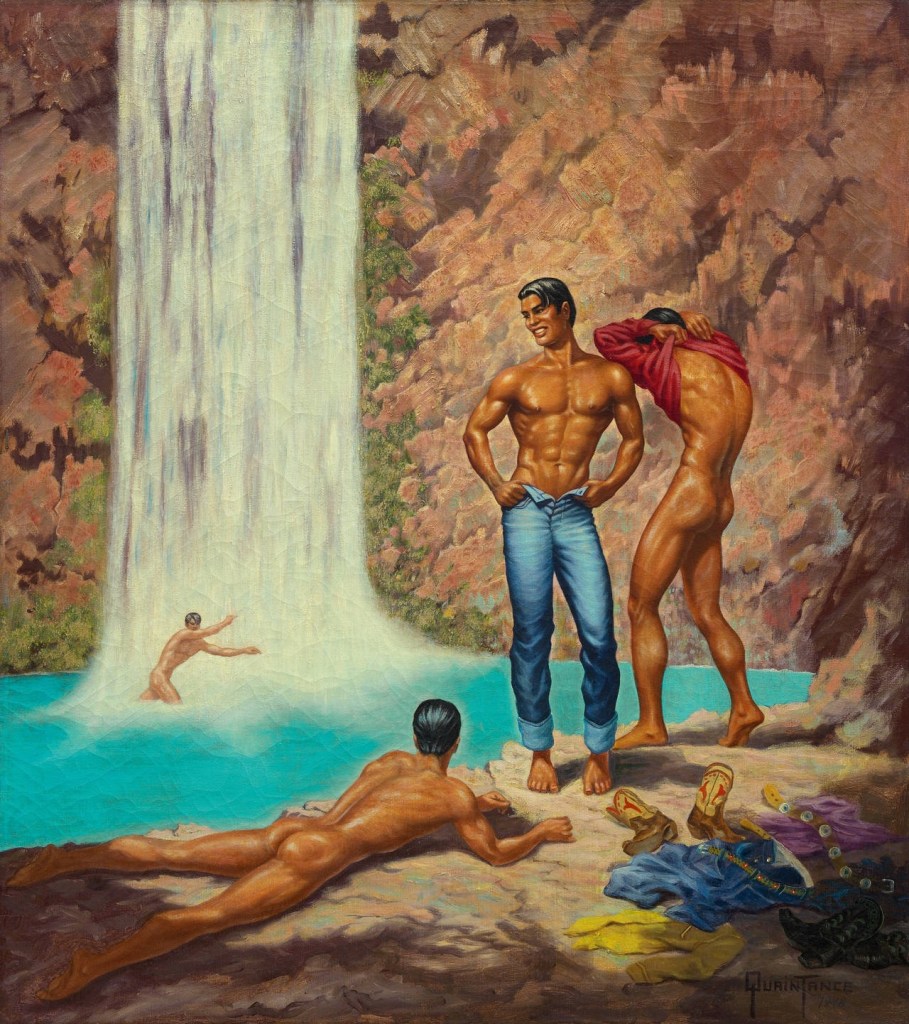

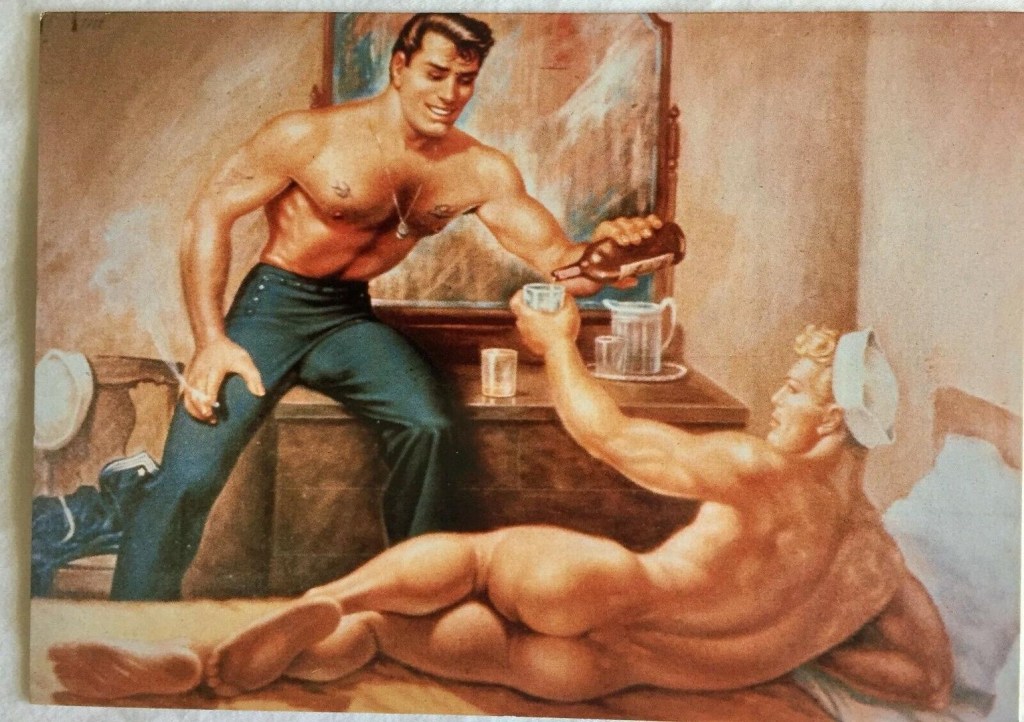

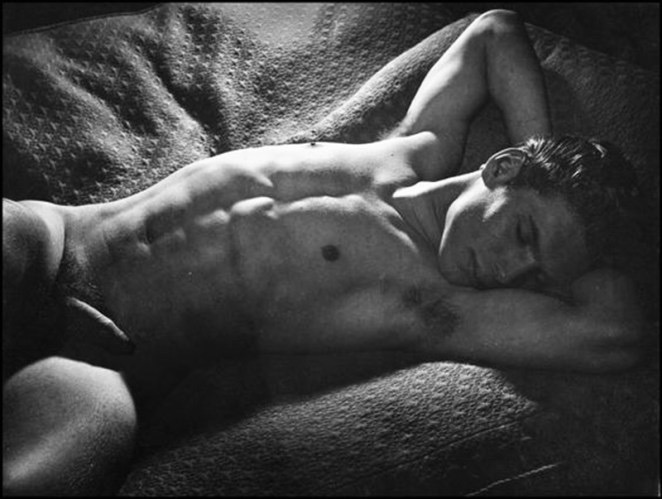

The Reclining Nude

Lying down, one arm behind the head, the other draped or trailing—the reclining male body exudes sensuality. Unlike the upright hero, the reclining nude invites the viewer in. It’s a pose of leisure, of trust, of soft exposure. In contemporary photography, it appears in the work of Robert Mapplethorpe and Herb Ritts, sometimes erotic, sometimes contemplative, but always intimate.

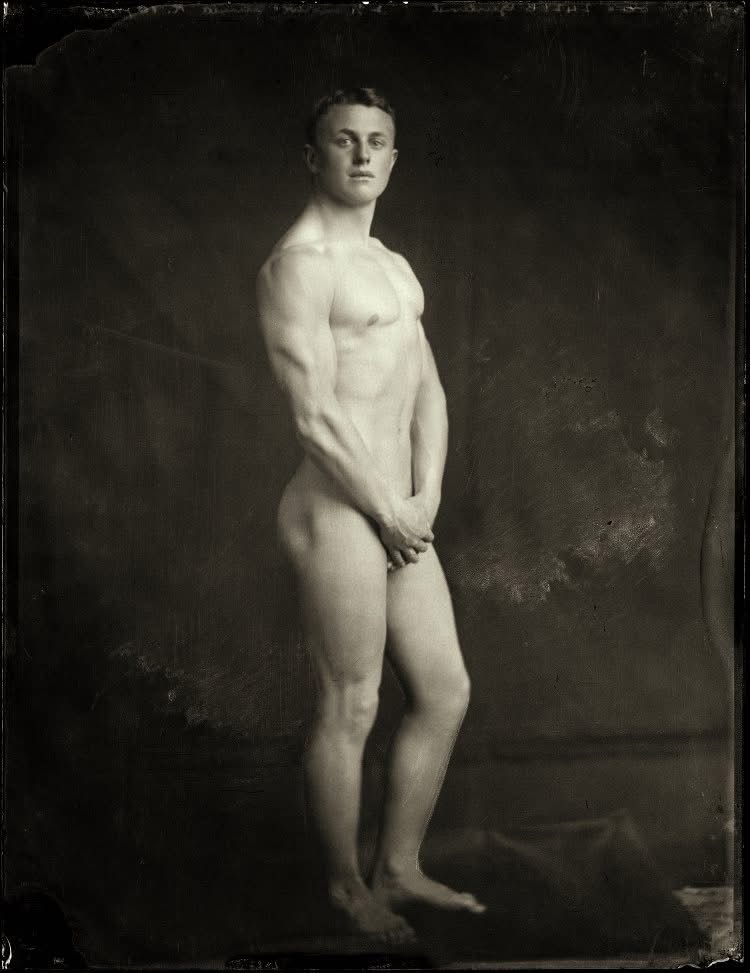

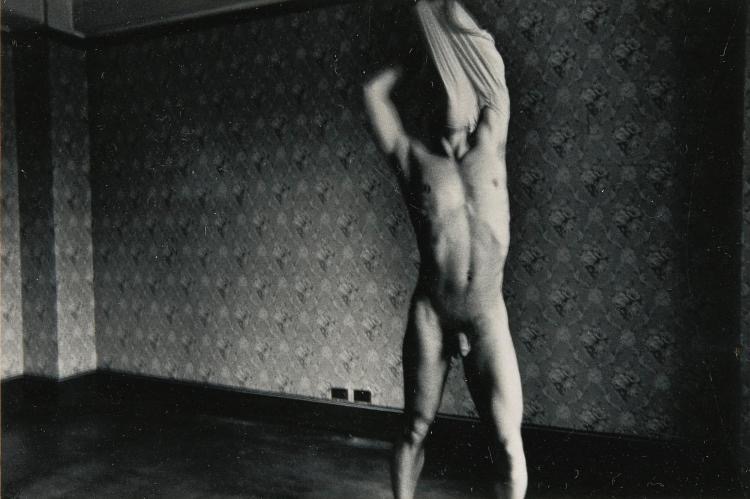

The Standing Frontal Nude

The fully frontal male nude remains one of the boldest artistic statements. It can convey power, but also deep vulnerability. With no turn of the hip or modest shadow, the body is presented in full—often rigid, symmetrical, and deliberately confronting the viewer. In photography, artists like George Platt Lynes and John Dugdale have used this pose to explore identity and embodiment with quiet boldness.

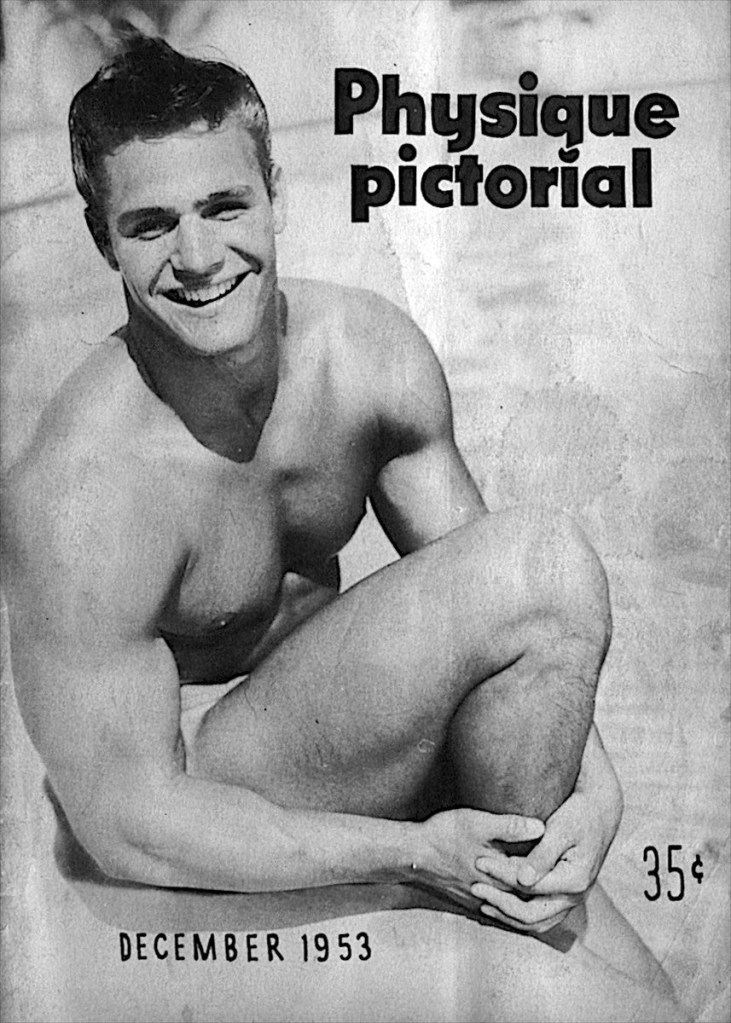

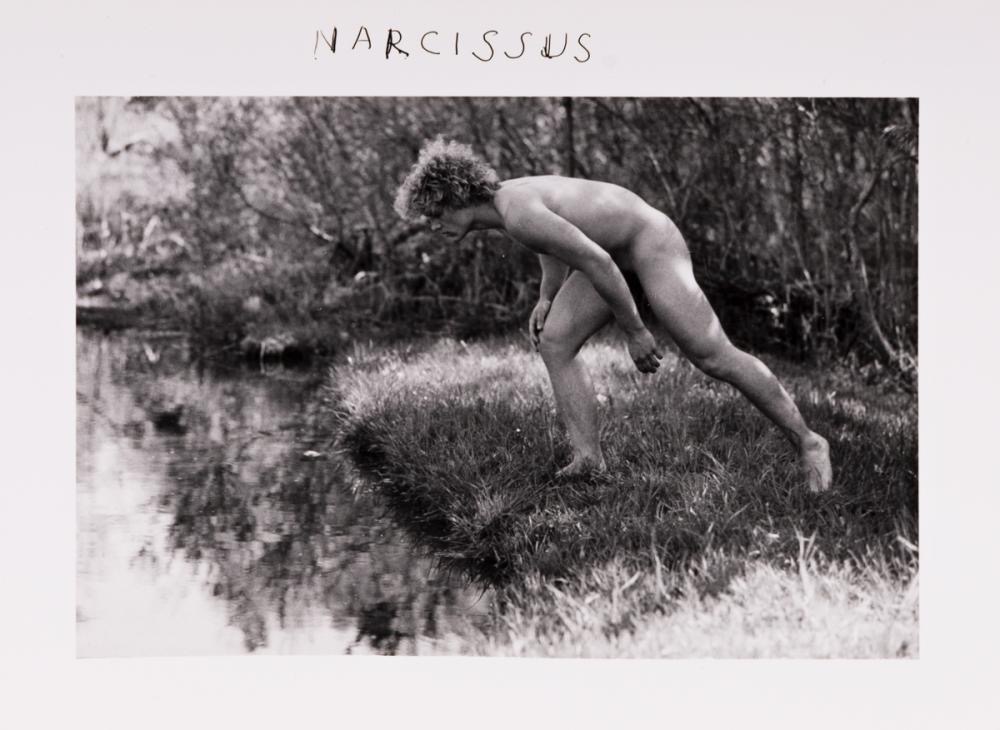

The Crouching Nude

Though more common with female nudes, the crouching pose has become a staple in expressive male photography—knees drawn up, torso folded inward, arms wrapped across chest or thighs. It signals protection, introspection, or erotic containment. Contemporary artists like Omar Z. Robles or Ren Hang have used this pose to convey psychological intimacy, even fragility.

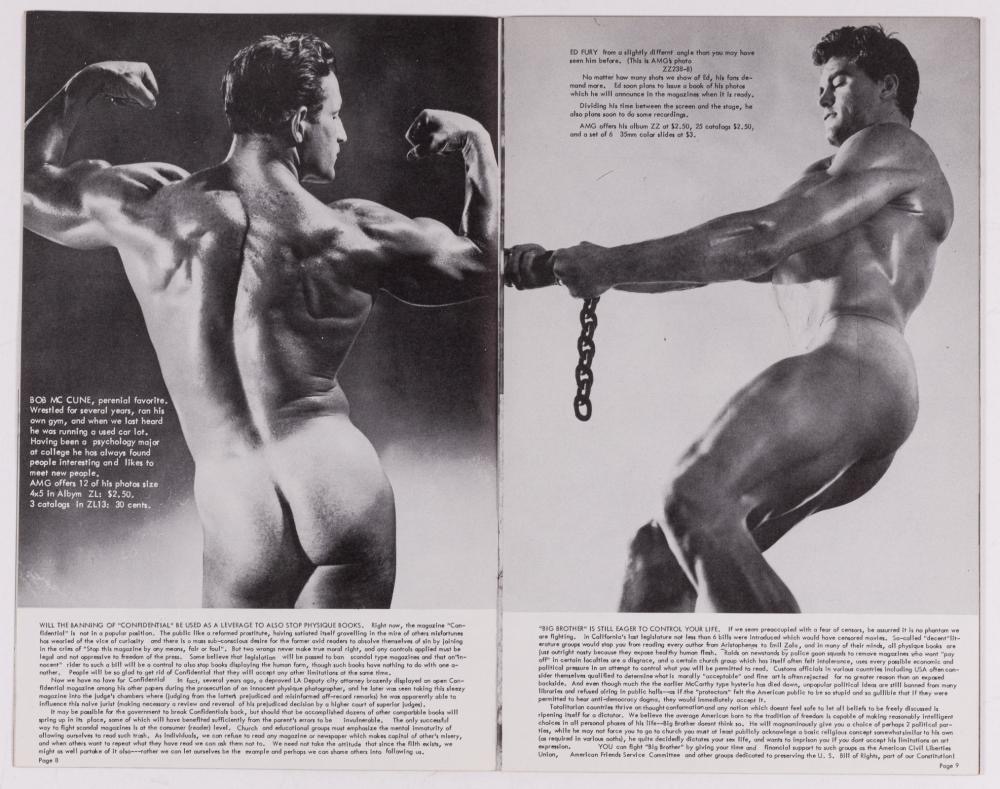

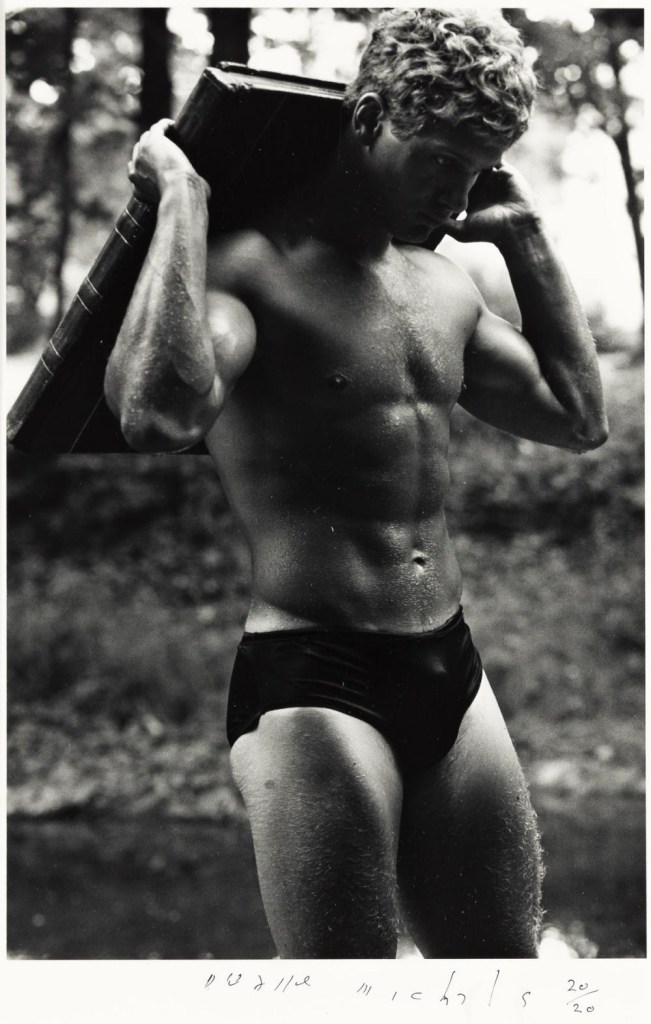

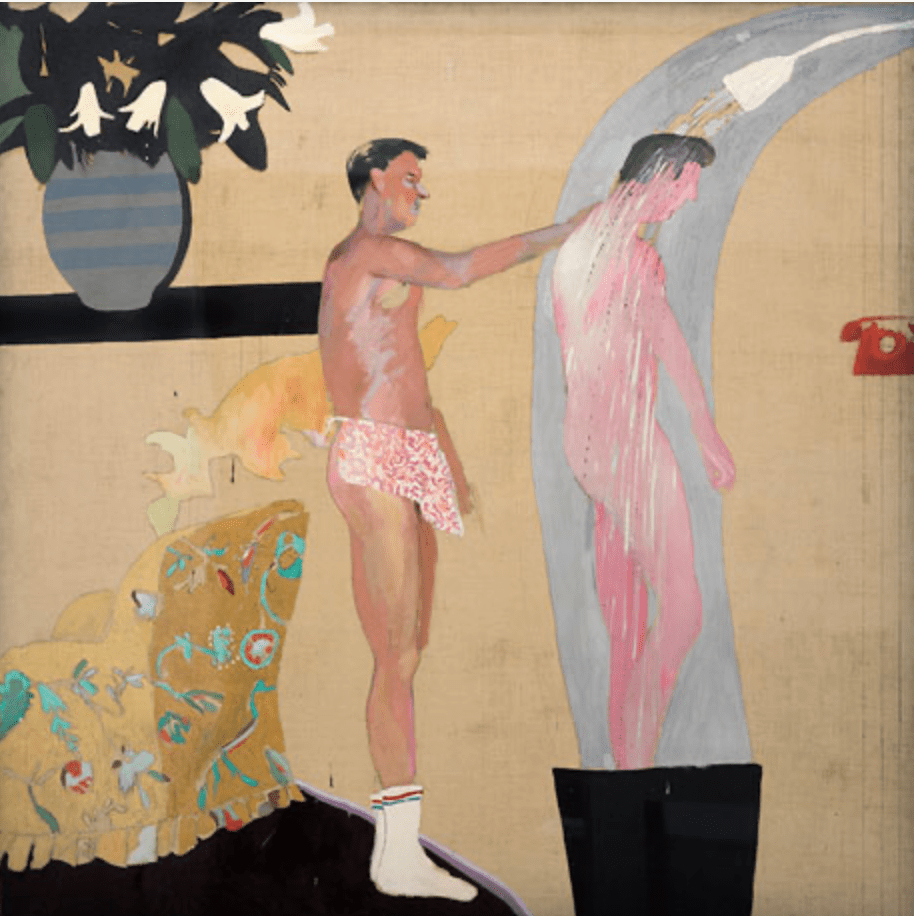

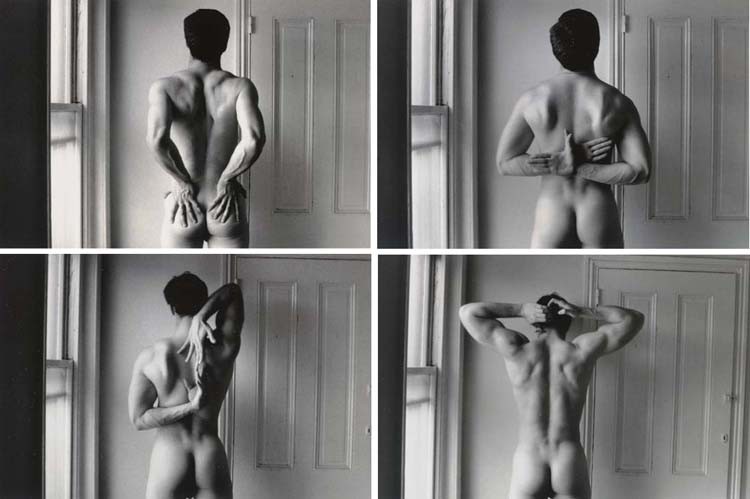

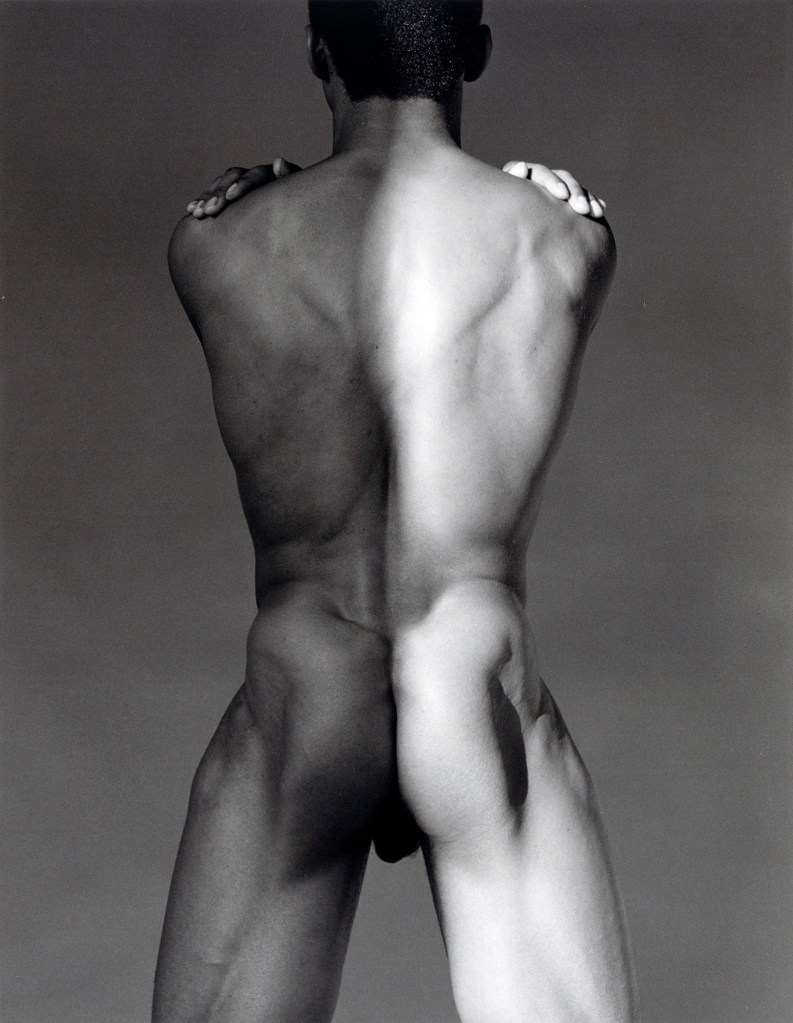

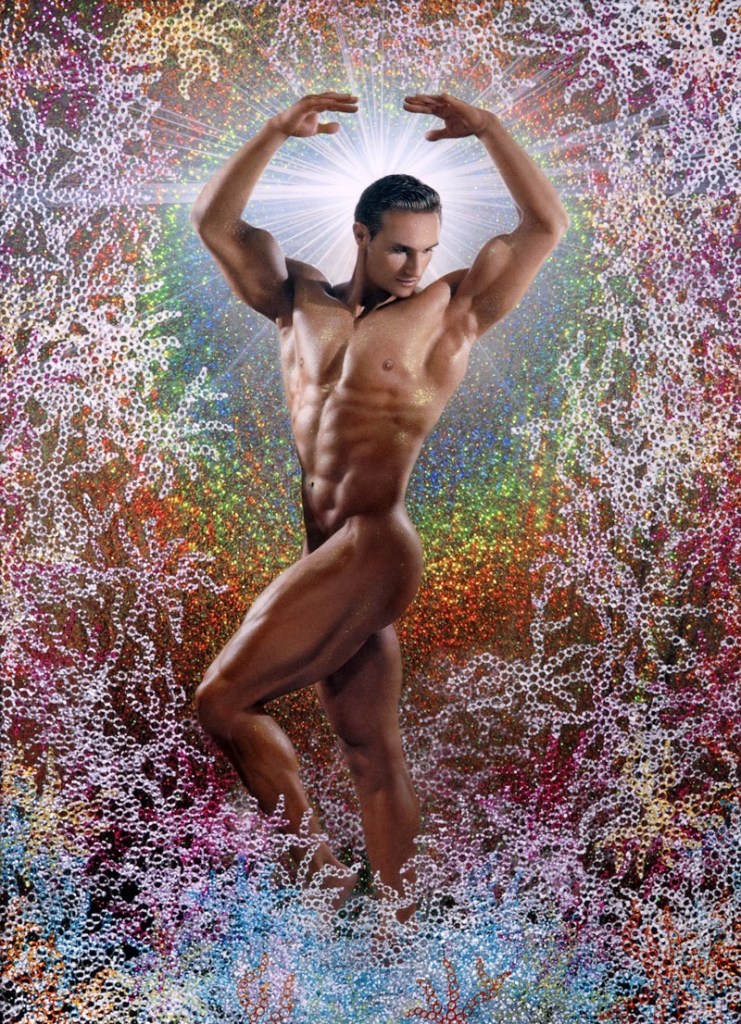

The Twisted Torso

Tension defines this pose—one limb pulled back, the torso twisted, spine coiled like a spring. It’s dynamic and dramatic, revealing musculature in full stretch and flex. In photographs, this pose dramatizes motion and often captures the male body mid-action—whether in dance, sport, or erotic tension. Think of dancer-turned-models in chiaroscuro-lit poses by photographers like Rick Day or Clive Barker.

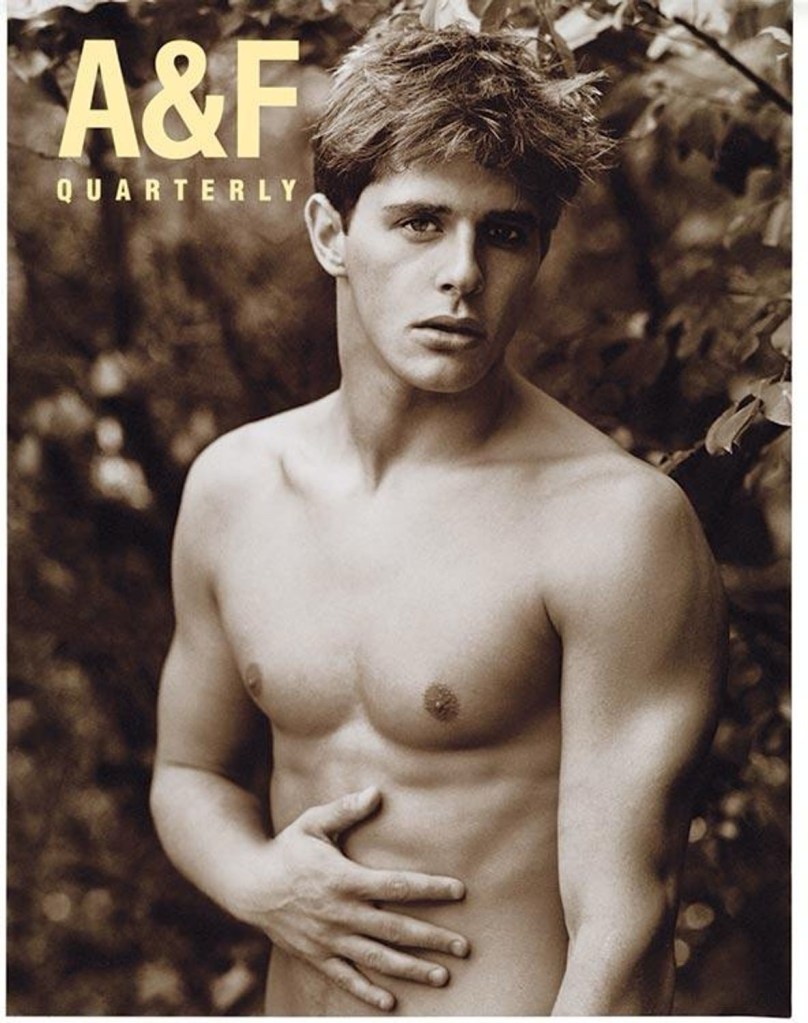

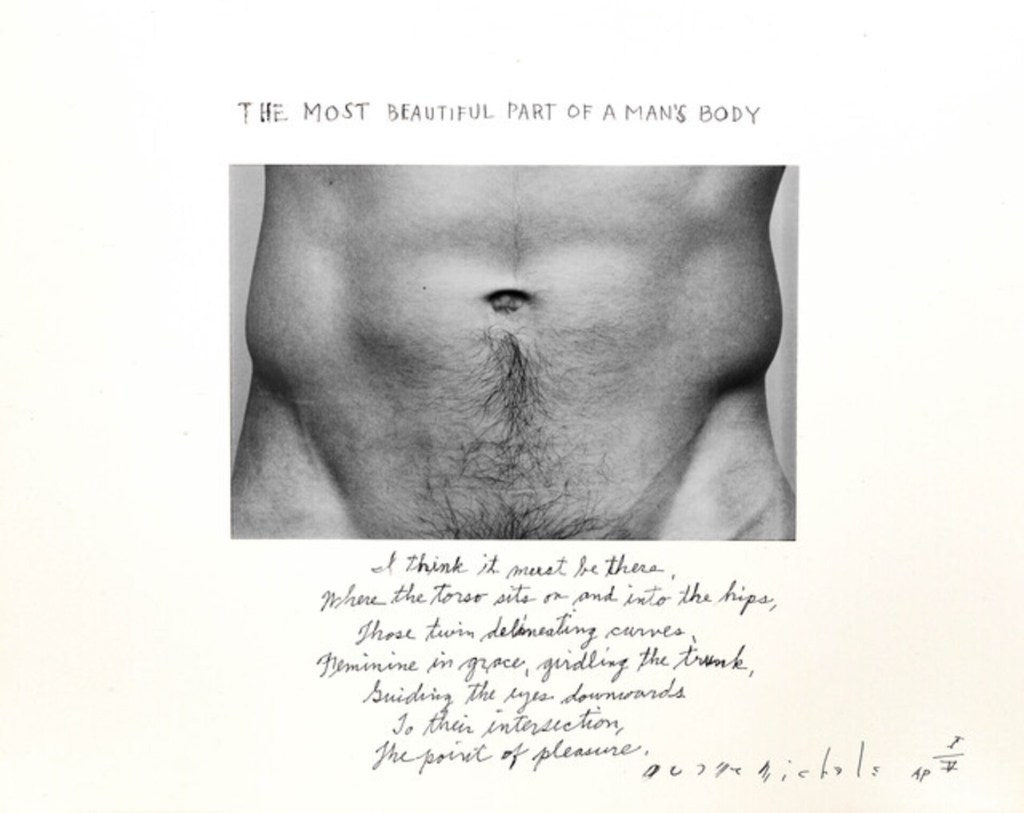

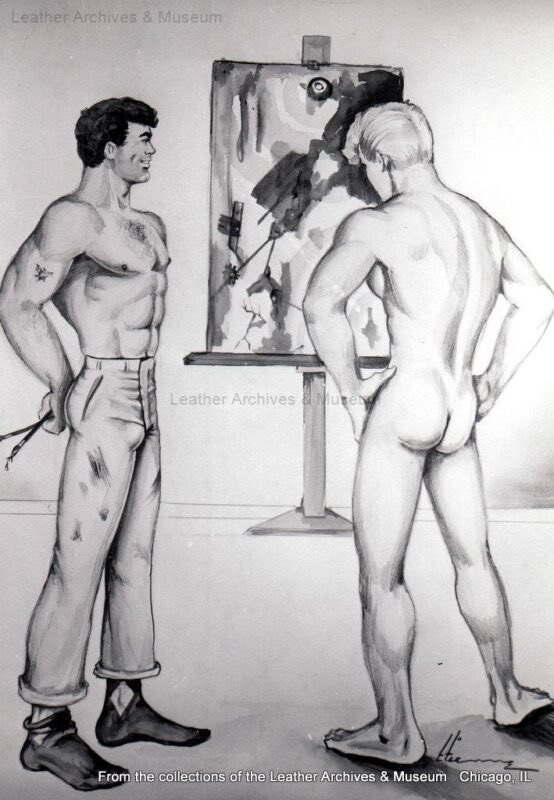

The Averted Gaze

This pose isn’t about the body so much as the gaze—or lack thereof. The male nude who looks away, whether shy, lost in thought, or caught in reverie, offers something emotionally elusive. In modern portraits, the averted gaze disarms the viewer: the nude isn’t performing for us, but existing despite us. It’s a favorite in modern queer portraiture, from artists like Duane Michals or Paul Freeman.

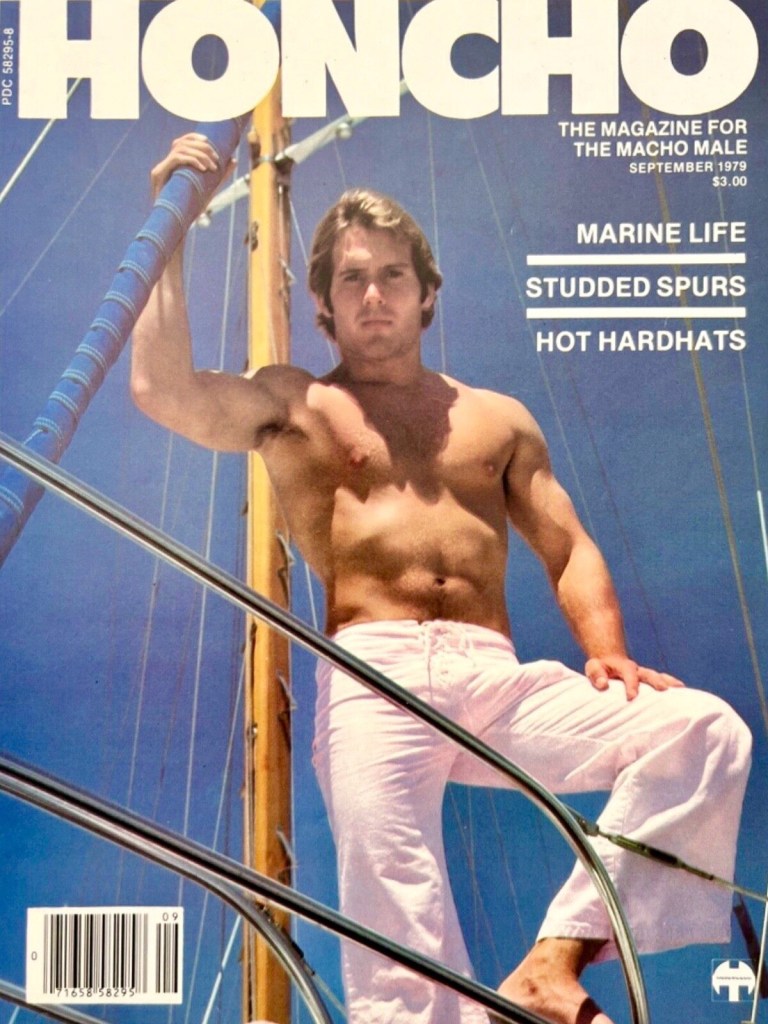

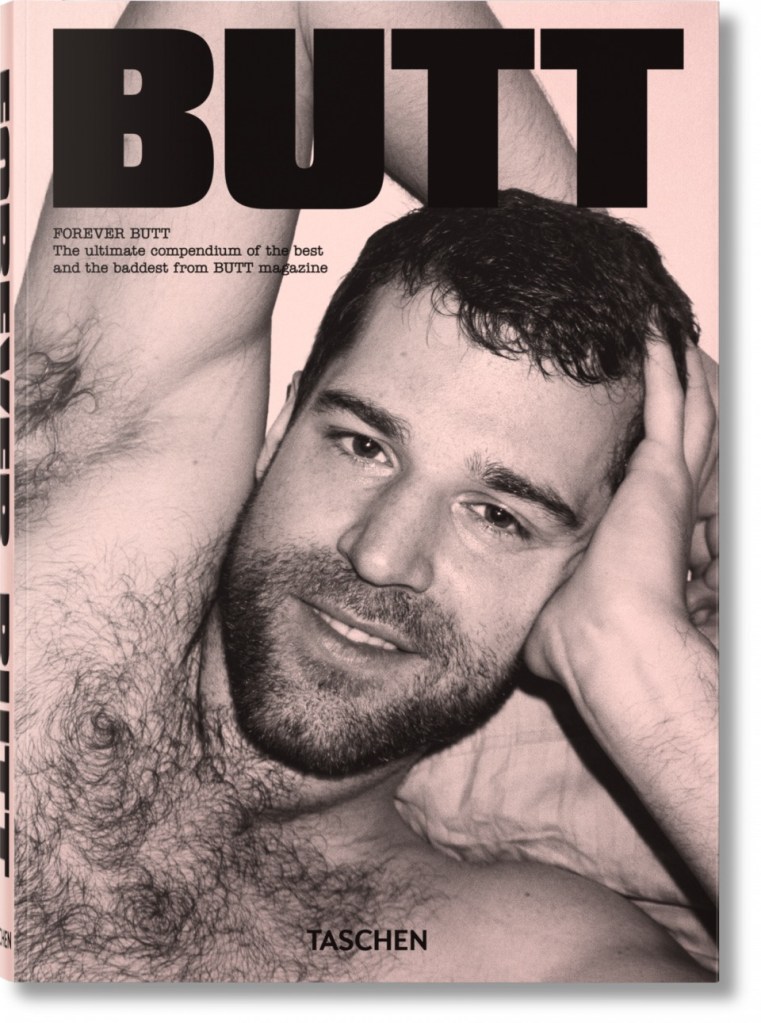

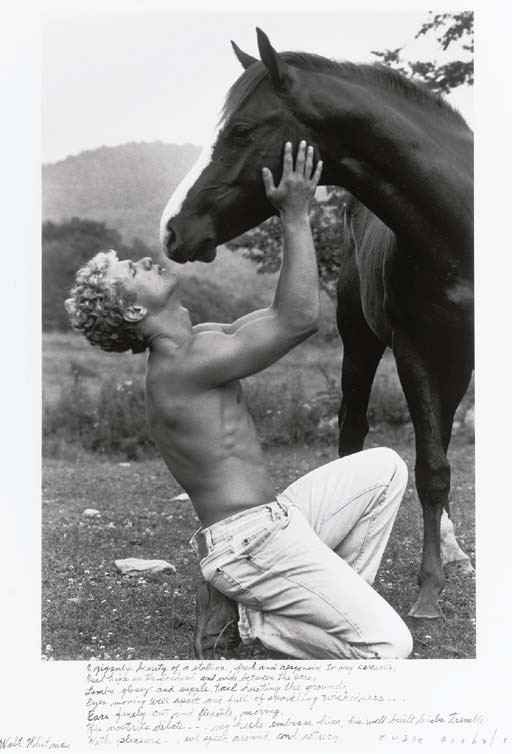

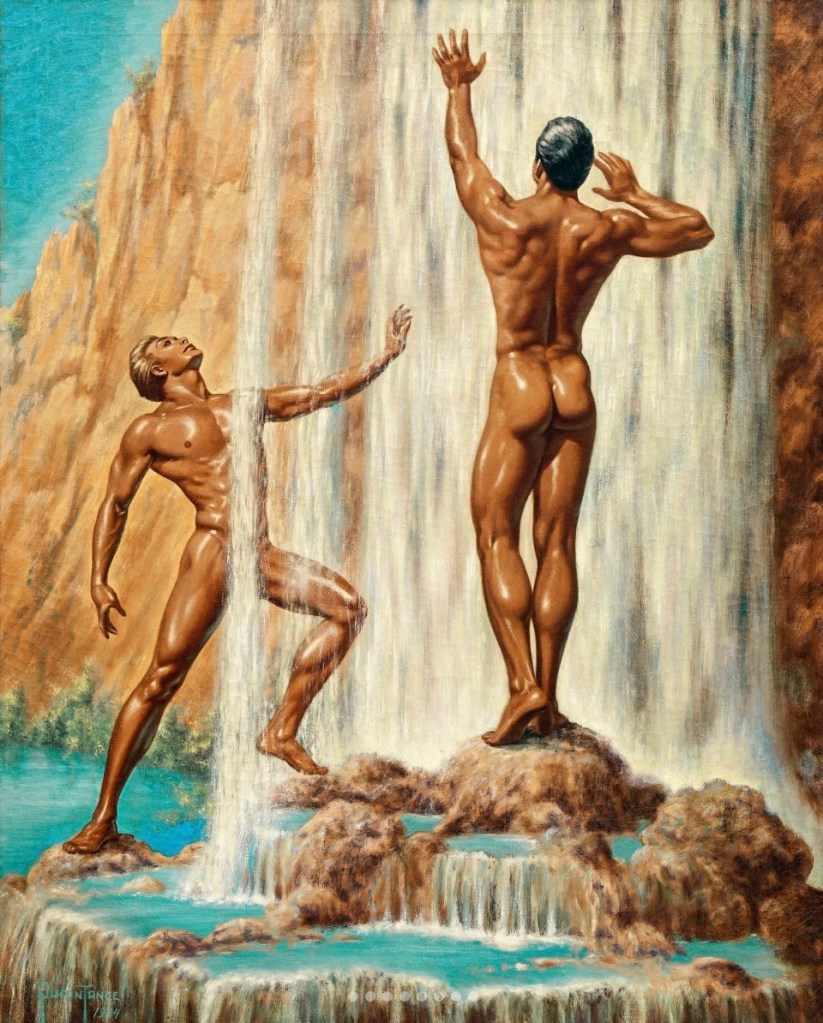

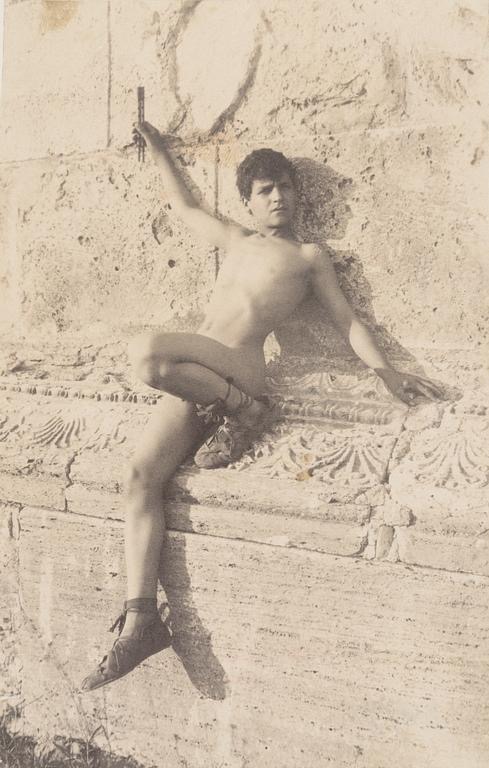

Arm Over Head — The Display of Strength and Vulnerability

An arm raised behind the head lengthens the body, stretching the torso and exposing the armpit—an often-erotic gesture in male imagery. Saint Sebastian, often portrayed in this pose, became a queer icon through his sensual vulnerability. Today, this pose appears in both fitness photography and erotic art, especially where strength and submission intertwine.

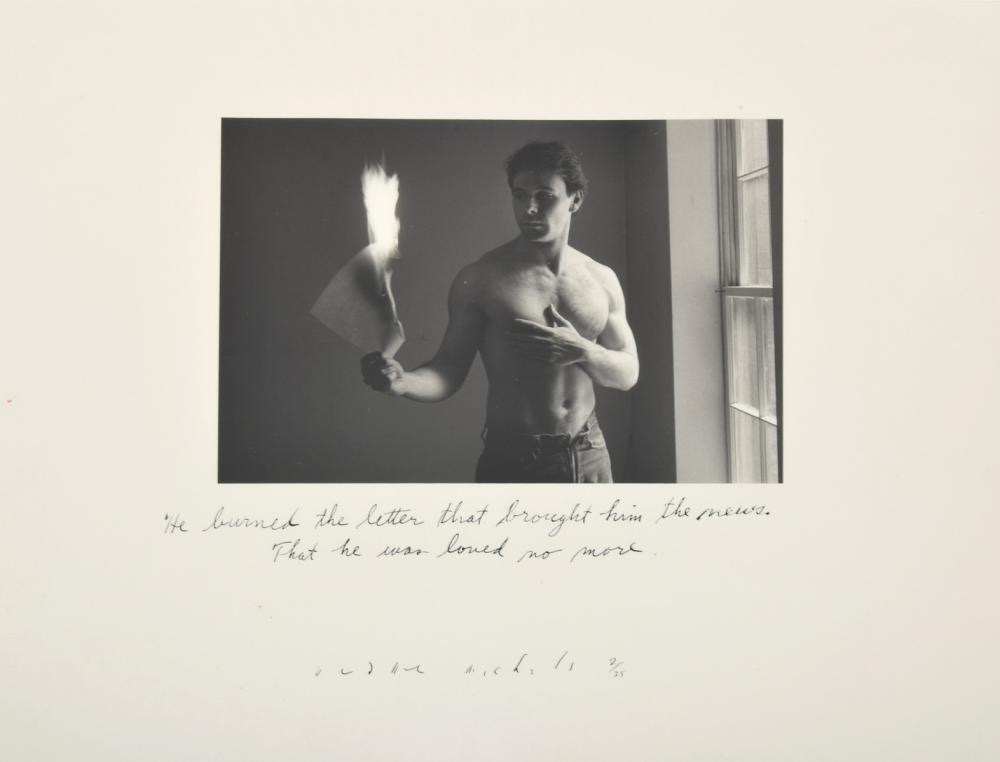

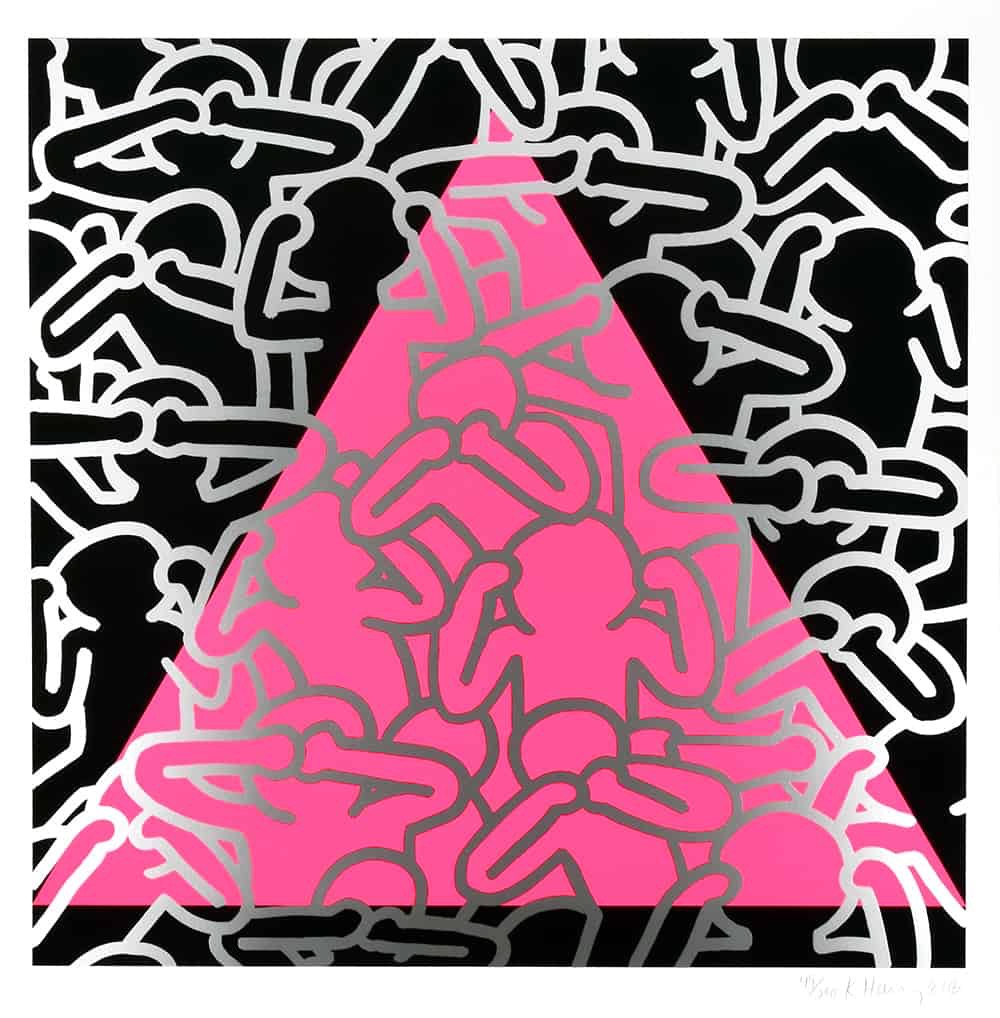

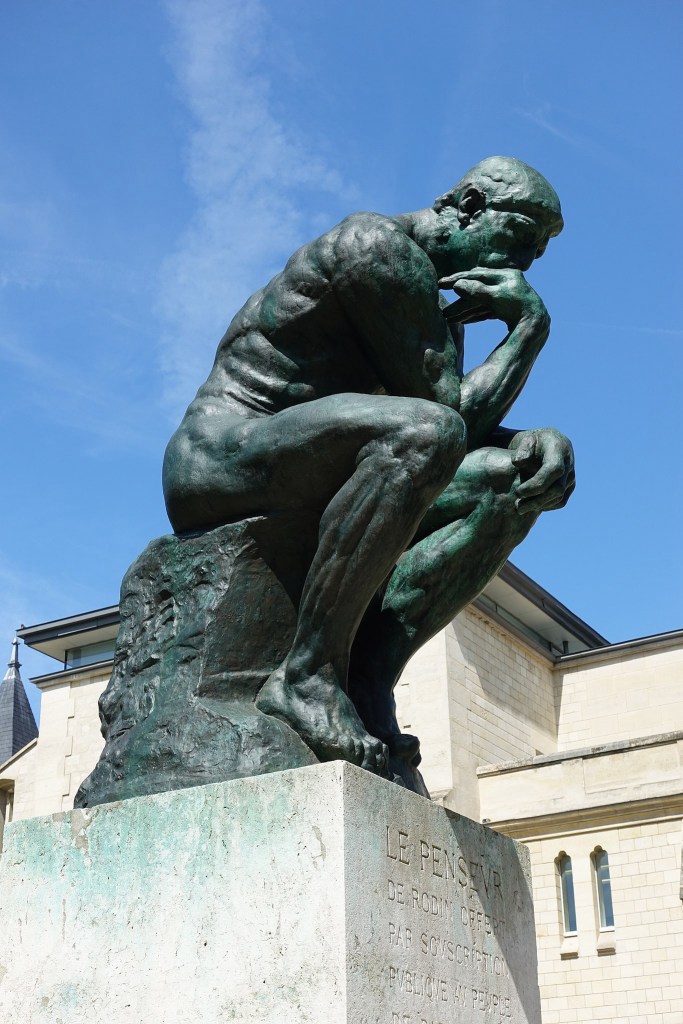

Memento Mori — The Nude and Mortality

This pose shows the male body entwined with symbols of death—a skull, a candle, a vacant stare. The man may be seated, leaning on one arm, lost in thought or grief. The erotic body meets existential dread. In contemporary queer art, this pose often reappears in AIDS-era photography—Peter Hujar and David Wojnarowicz come to mind—where the beauty of the body confronts its own impermanence.

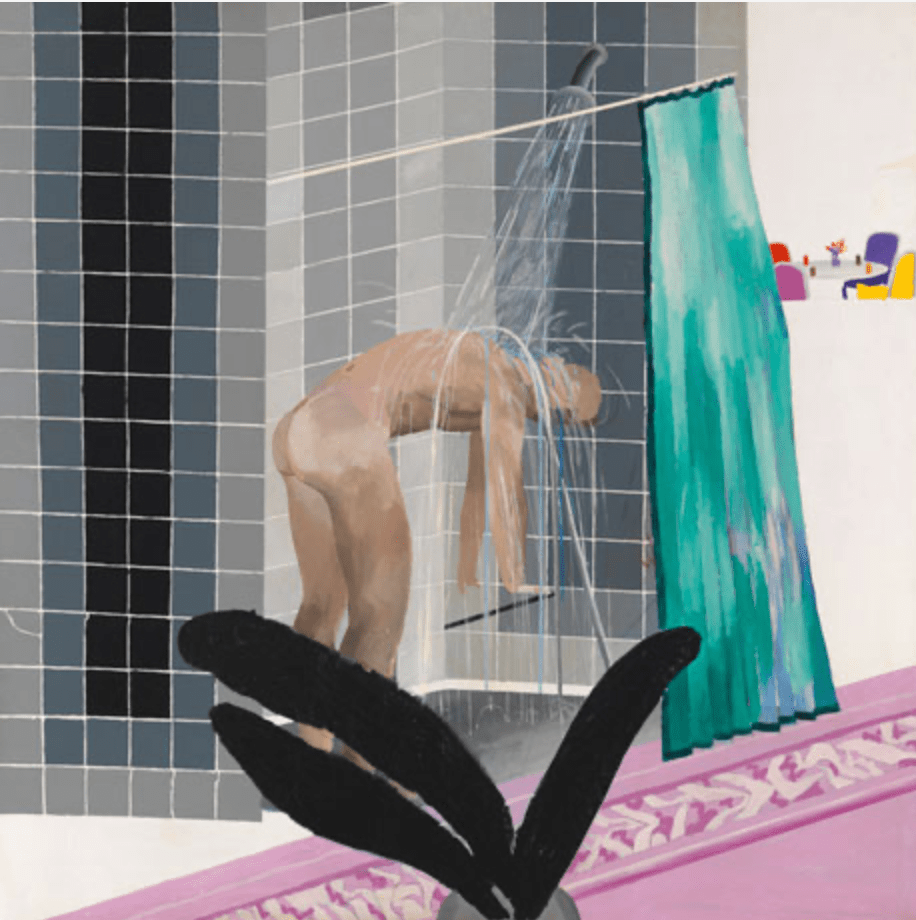

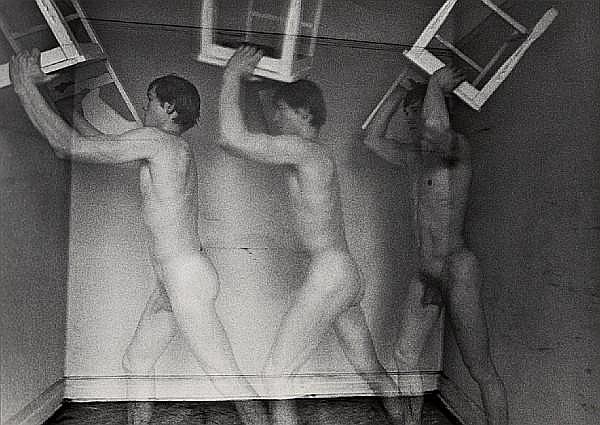

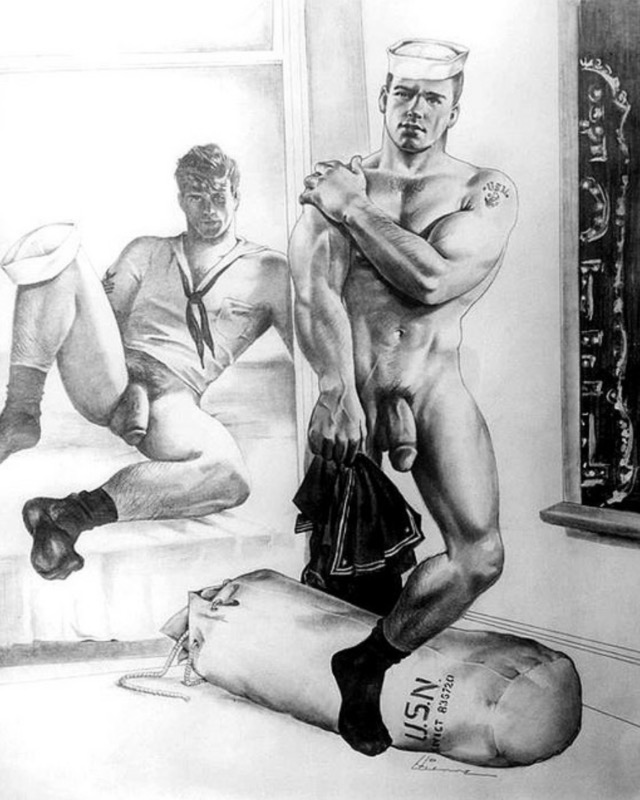

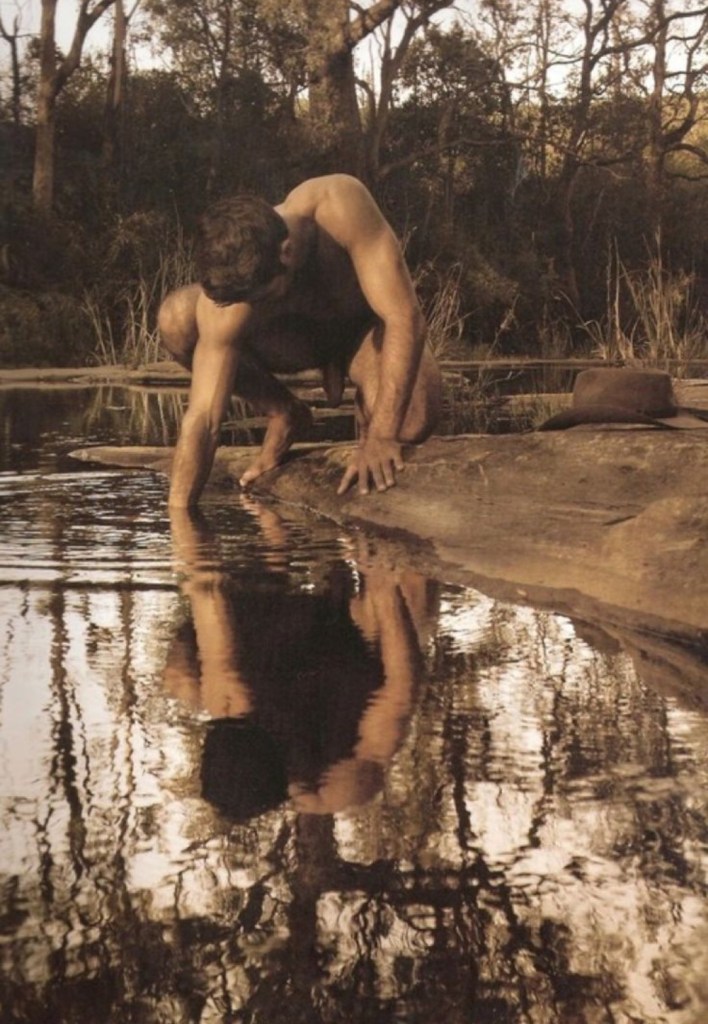

The Mirror Pose

The male nude gazing at his reflection—either literally or metaphorically—carries a rich history of both vanity and self-awareness. In modern work, this pose has become a commentary on queer desire, identity, and self-recognition. Whether through mirrored images, doubled exposures, or paired models, the mirrored pose flirts with the erotic and the existential: Who do we see when we look at ourselves?

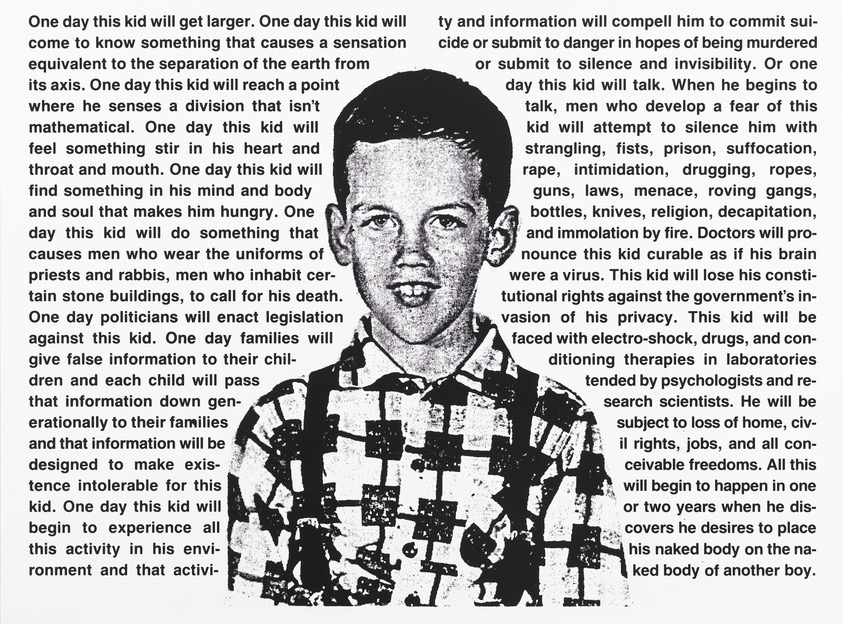

These poses, repeated across millennia, aren’t just about aesthetics—they’re about how we’ve viewed the male body and the roles it plays: protector, object of desire, thinker, vessel of strength or sorrow. And in queer art especially, these poses become subversive. They reclaim what was once coded and hidden, turning vulnerability into power and eroticism into expression.

Whether sculpted in marble, captured in monochrome, or filtered through a digital lens, the male nude continues to speak a visual language of longing, beauty, and identity. It’s a language many of us have learned to read—and some of us are still learning to write with our own bodies.