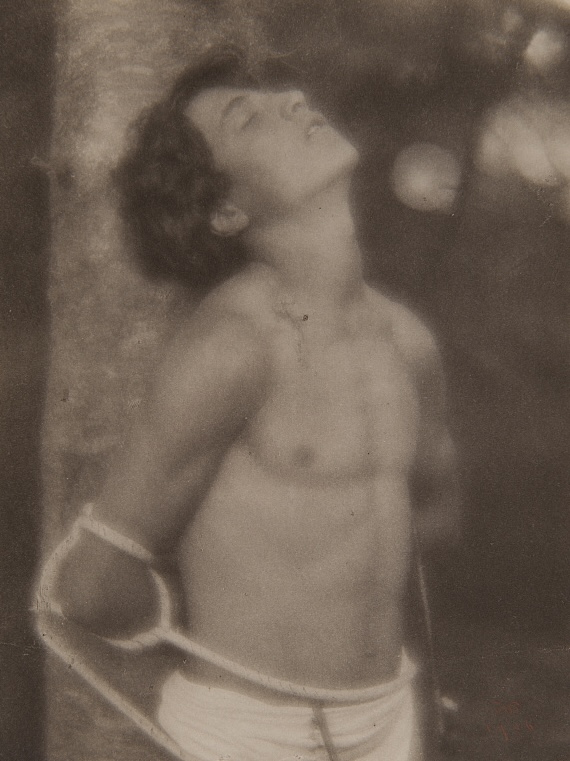

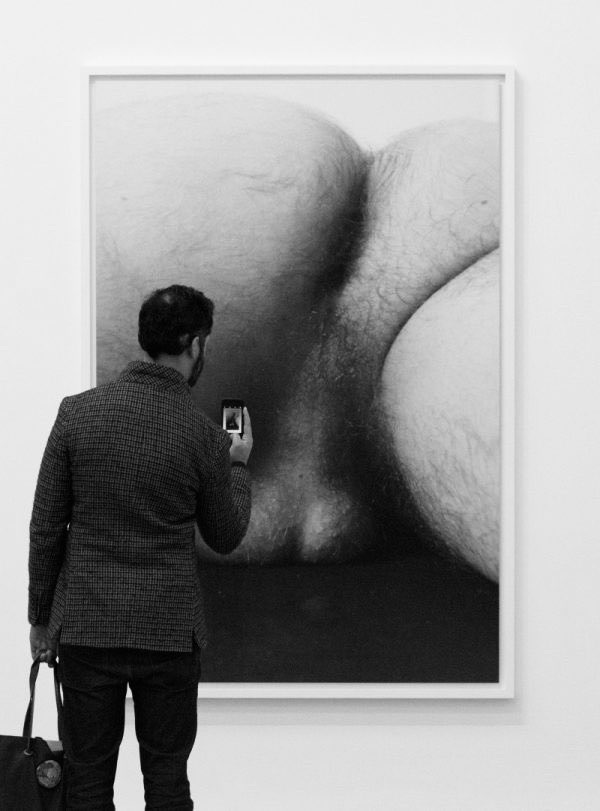

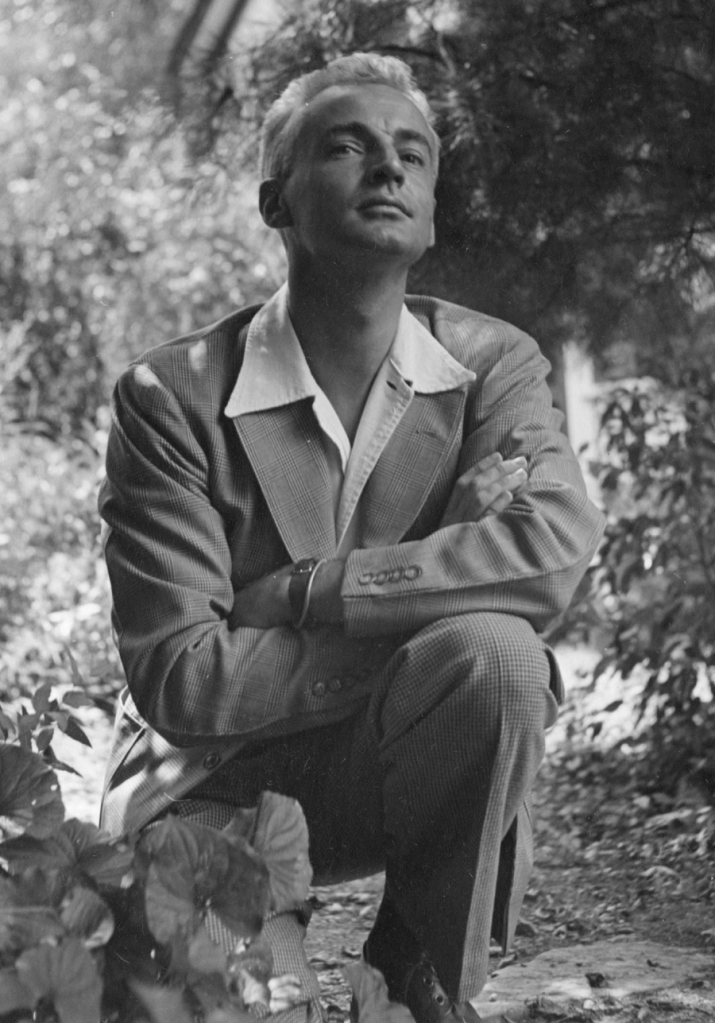

George Platt Lynes (1907–1955) occupies a unique and courageous place in 20th-century photography. Best known during his lifetime for his sophisticated fashion images and celebrity portraits, Lynes also created a substantial, deeply personal body of male nudes and homoerotic photographs. These images, radical for their time, remained largely hidden from public view for decades. Today, they stand not only as remarkable works of art but also as rare, defiant records of queer desire in a period of profound social repression.

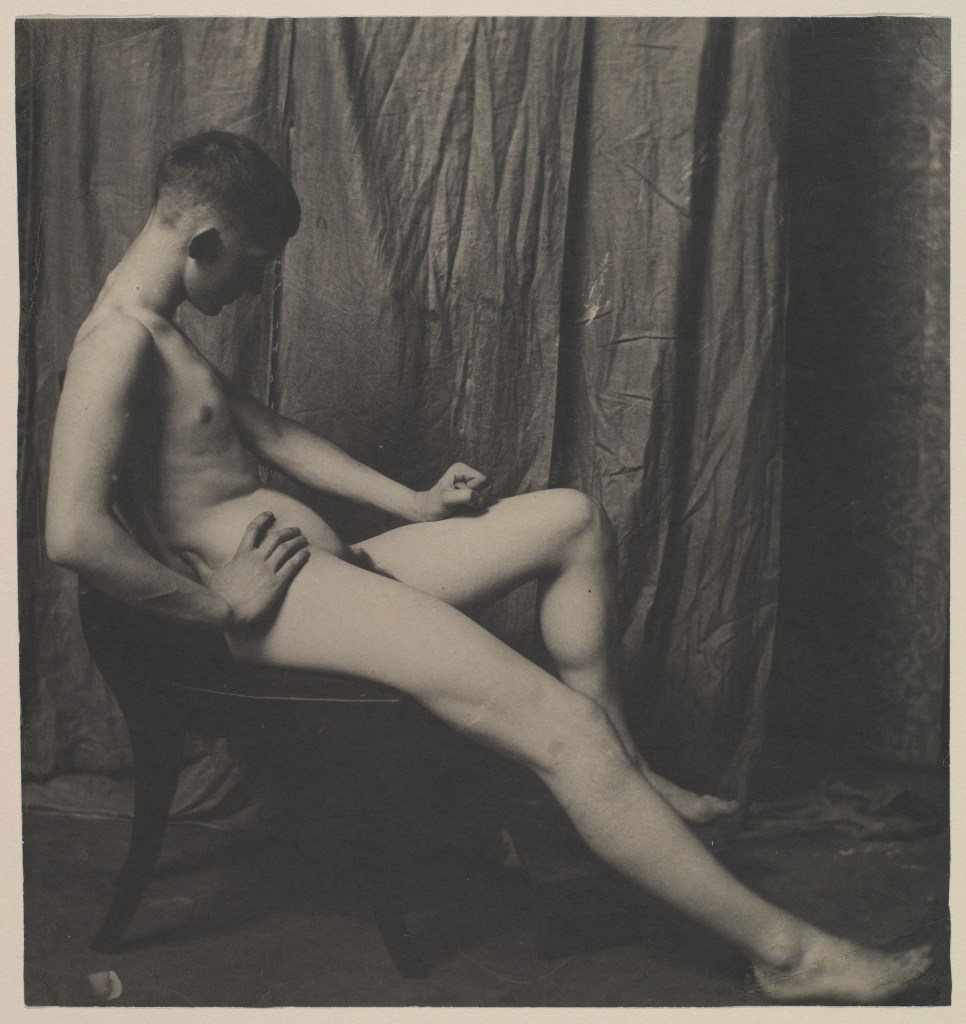

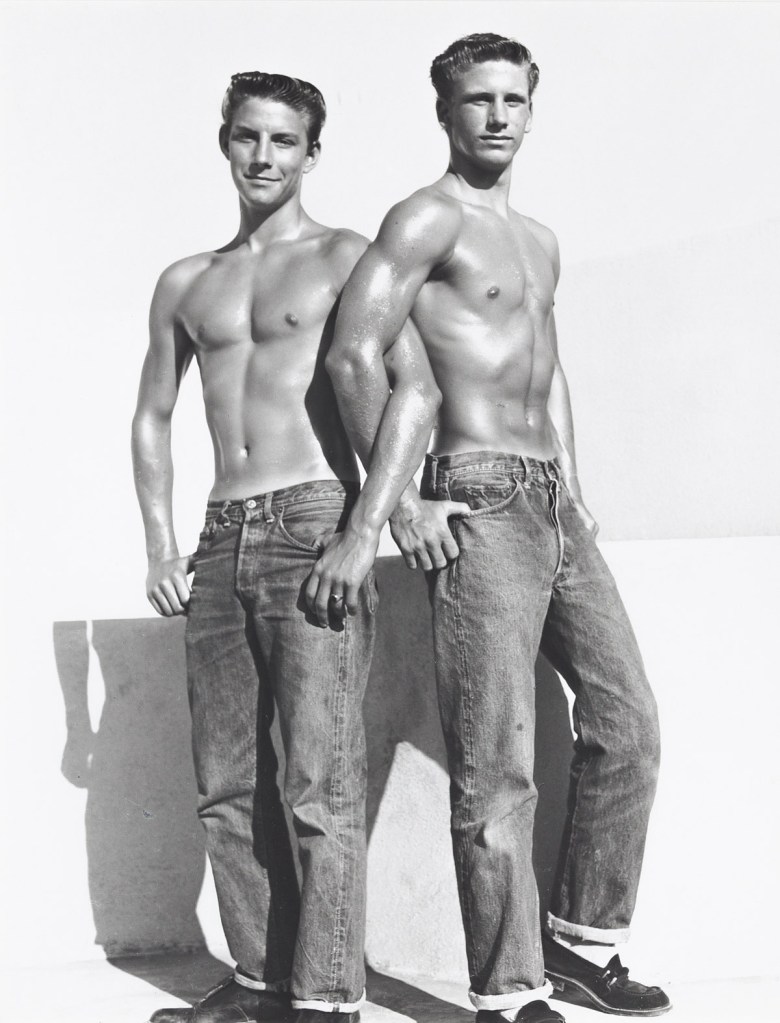

Lynes began his career in the 1920s and 1930s, becoming a sought-after fashion photographer for Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, and Town & Country. His images were noted for their theatricality, stylization, and mythic undertones. Yet, while he achieved success in commercial photography, he was simultaneously pursuing a private and more dangerous artistic project: photographing nude men, often friends, performers, and lovers.

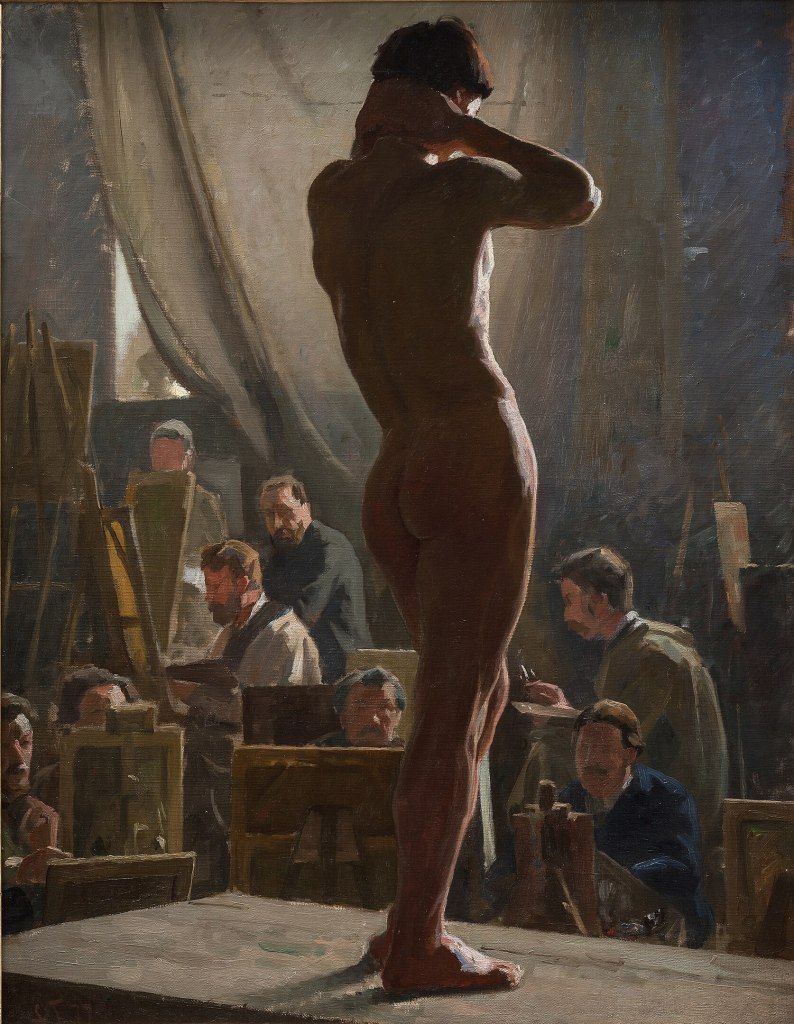

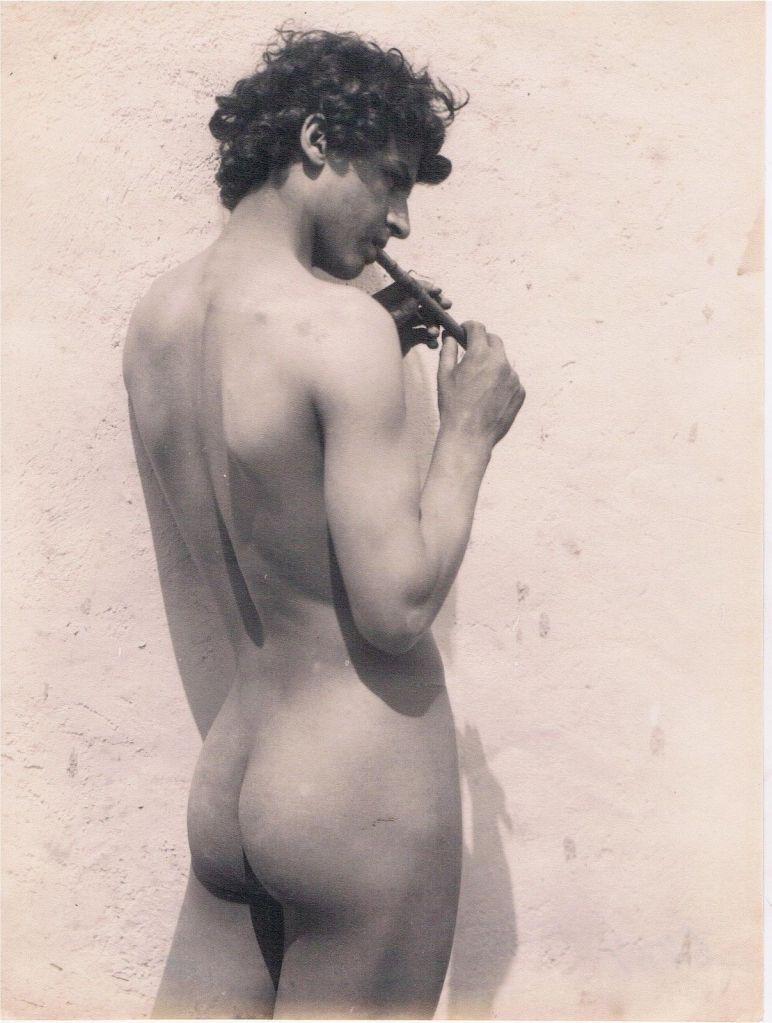

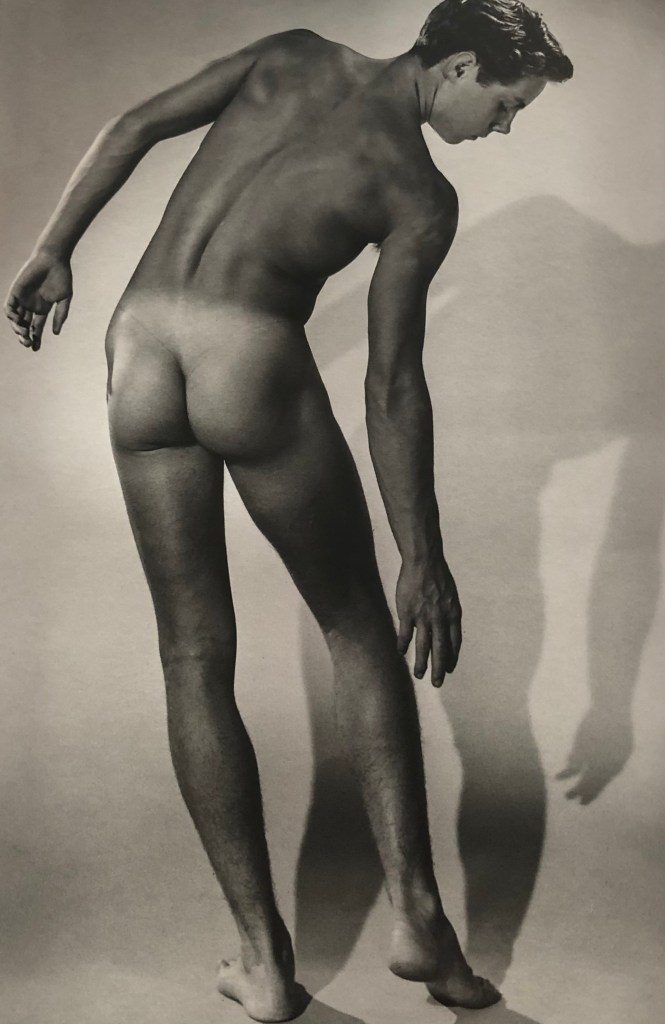

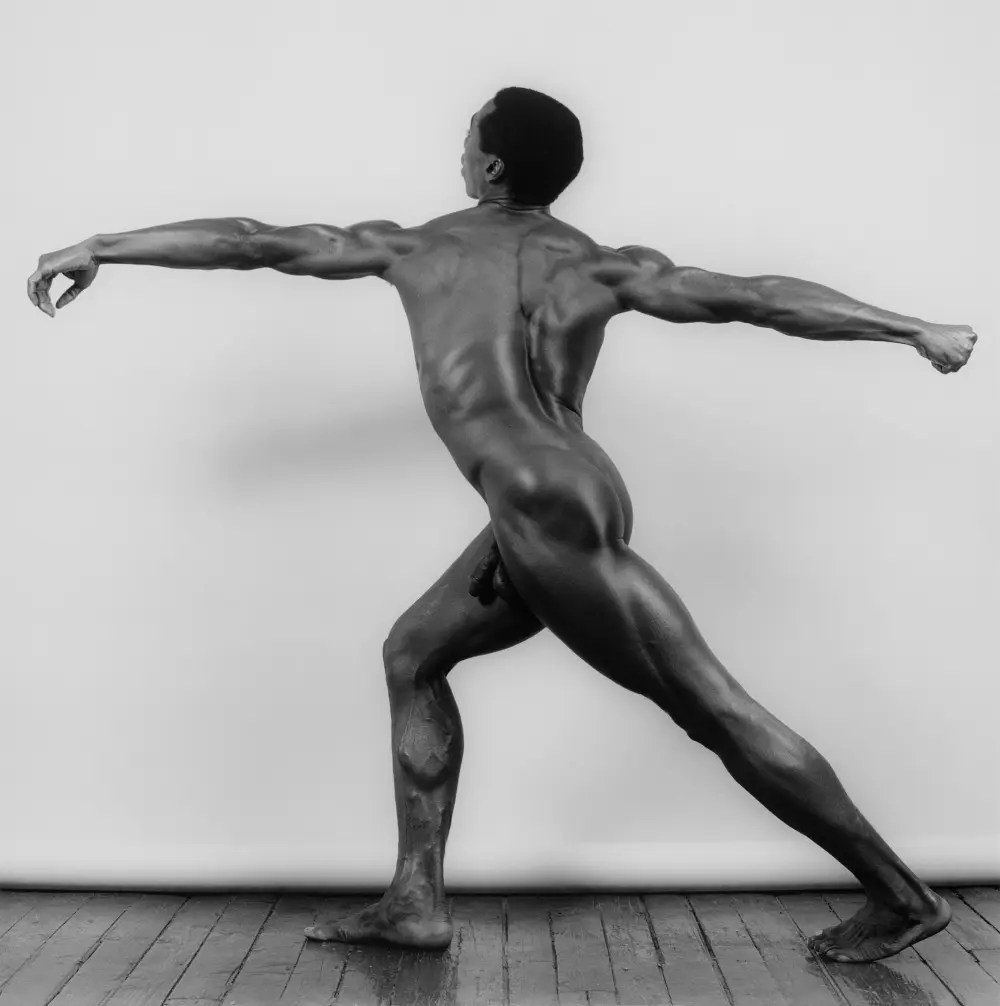

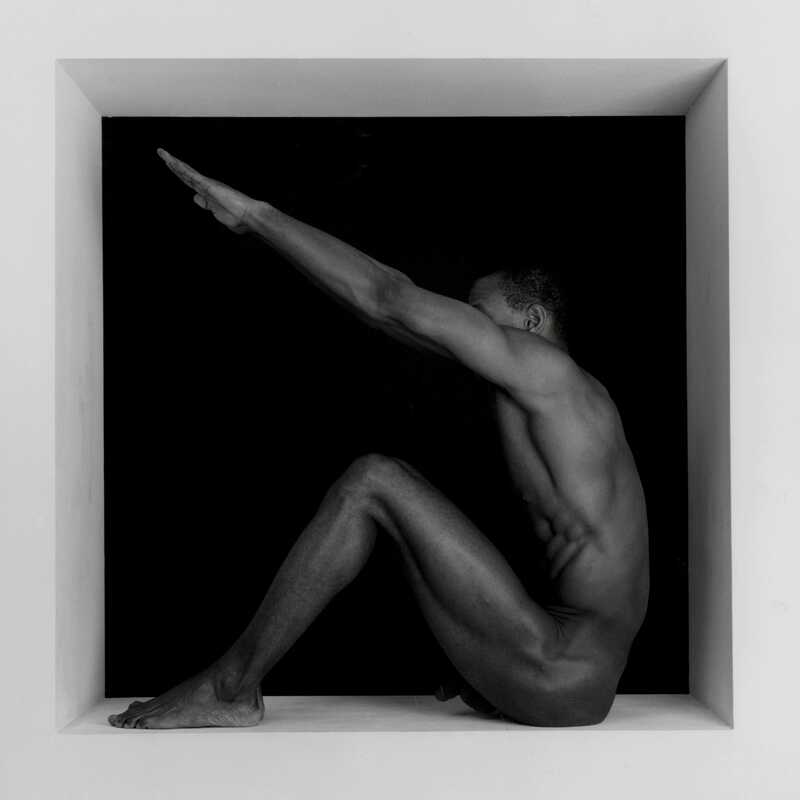

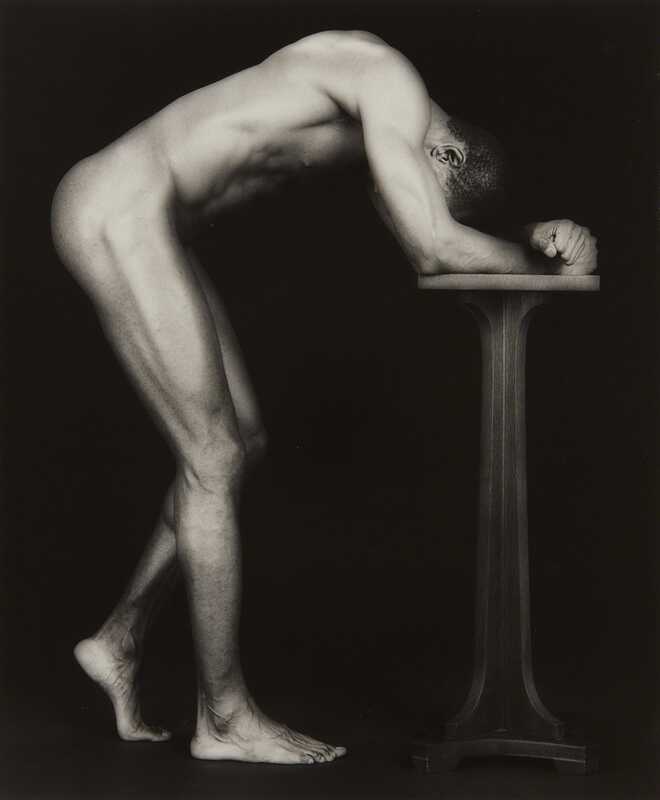

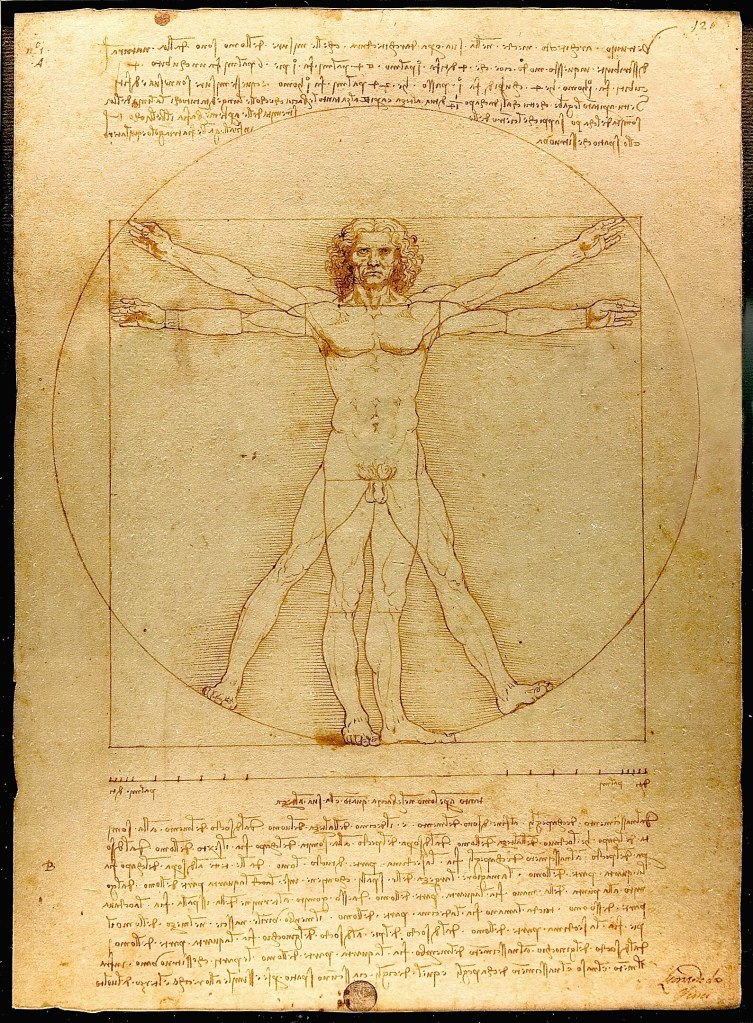

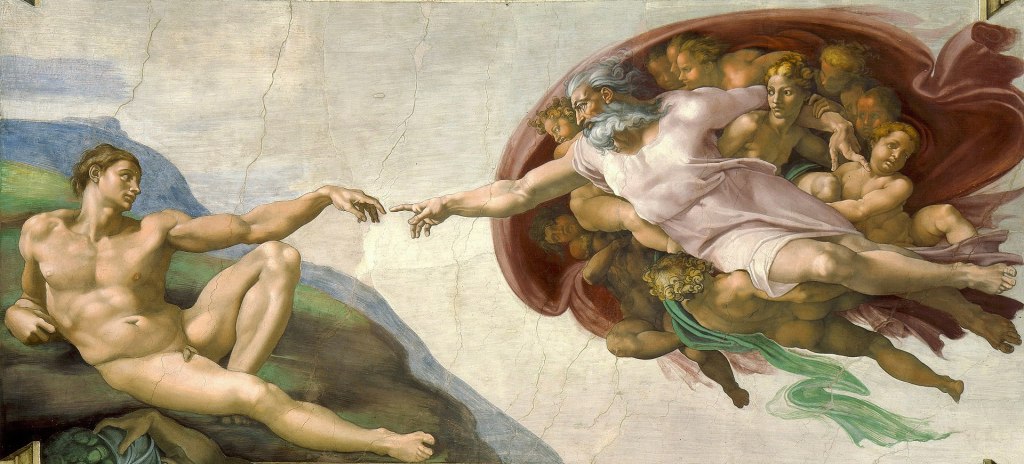

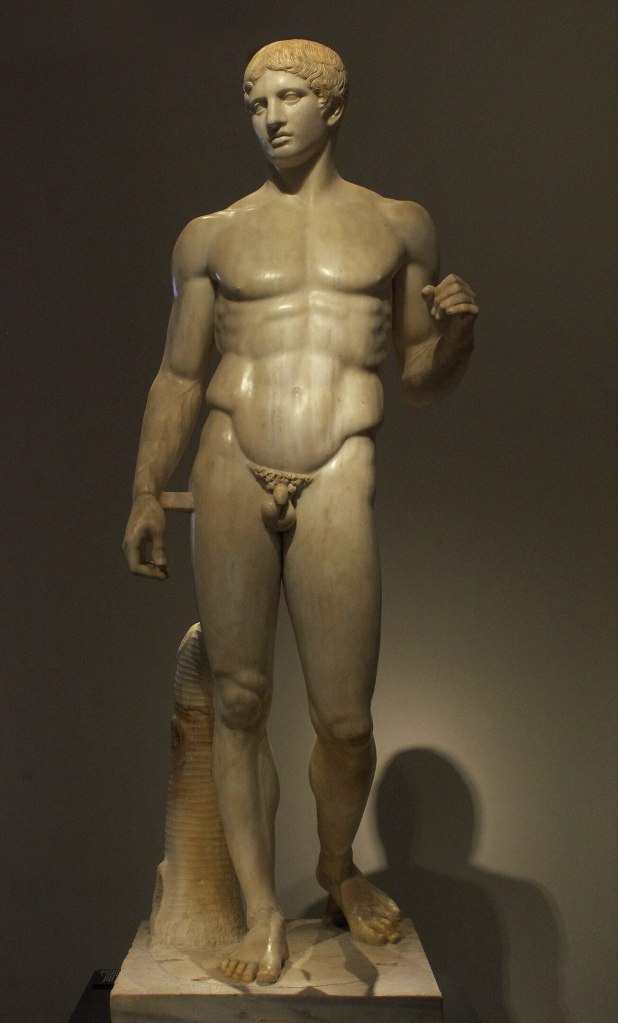

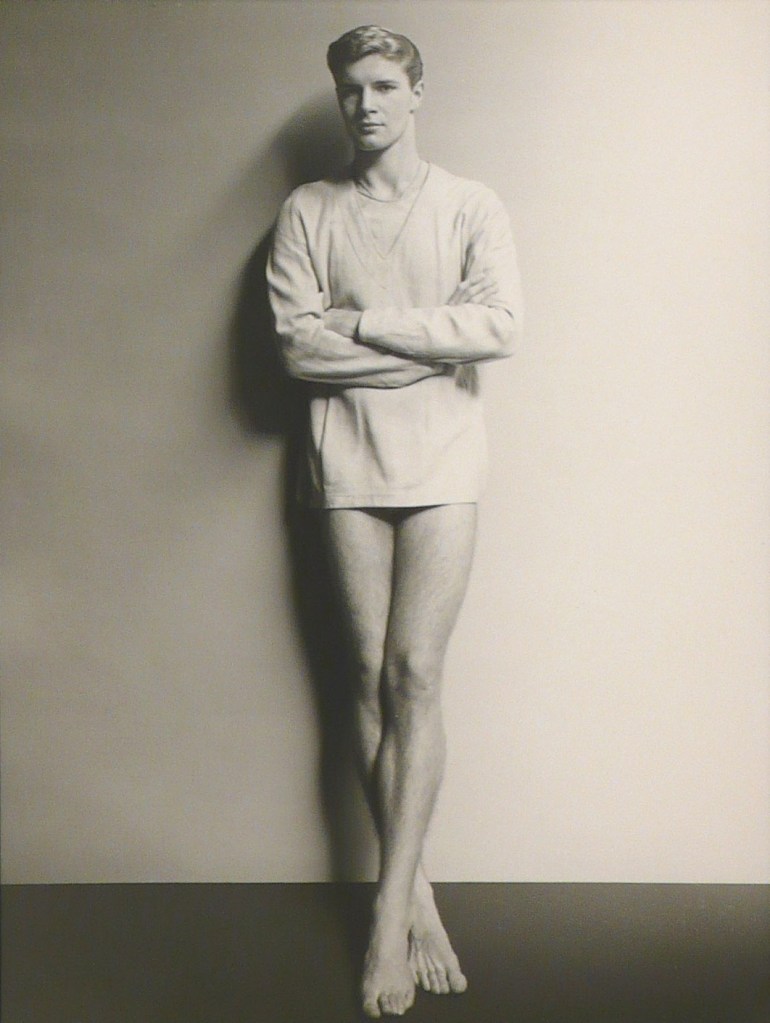

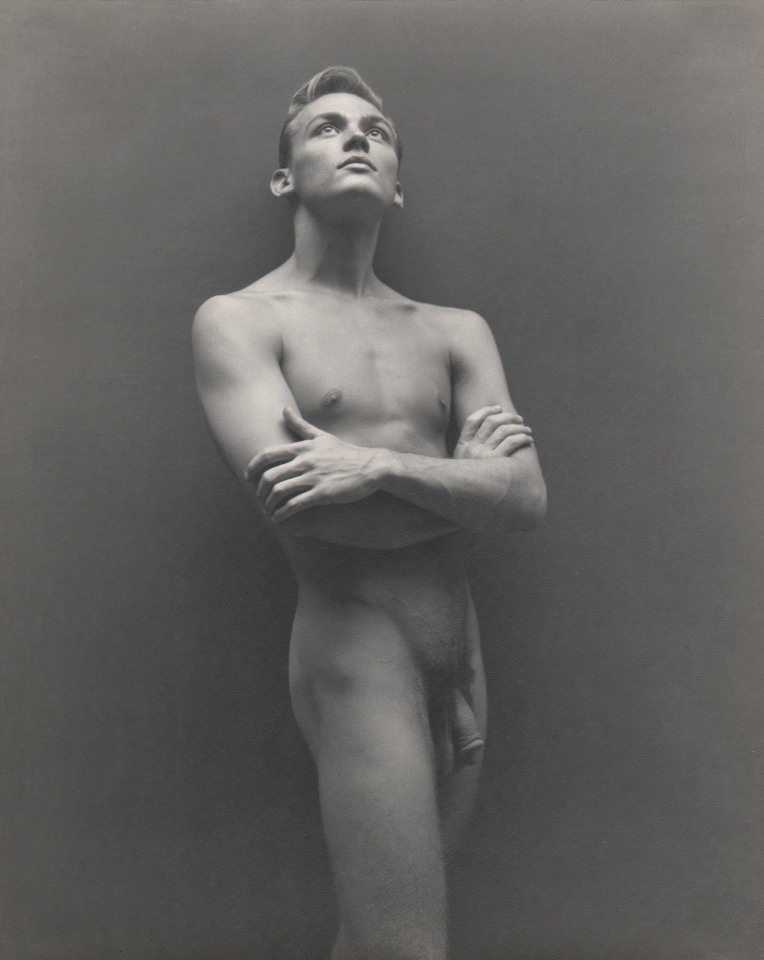

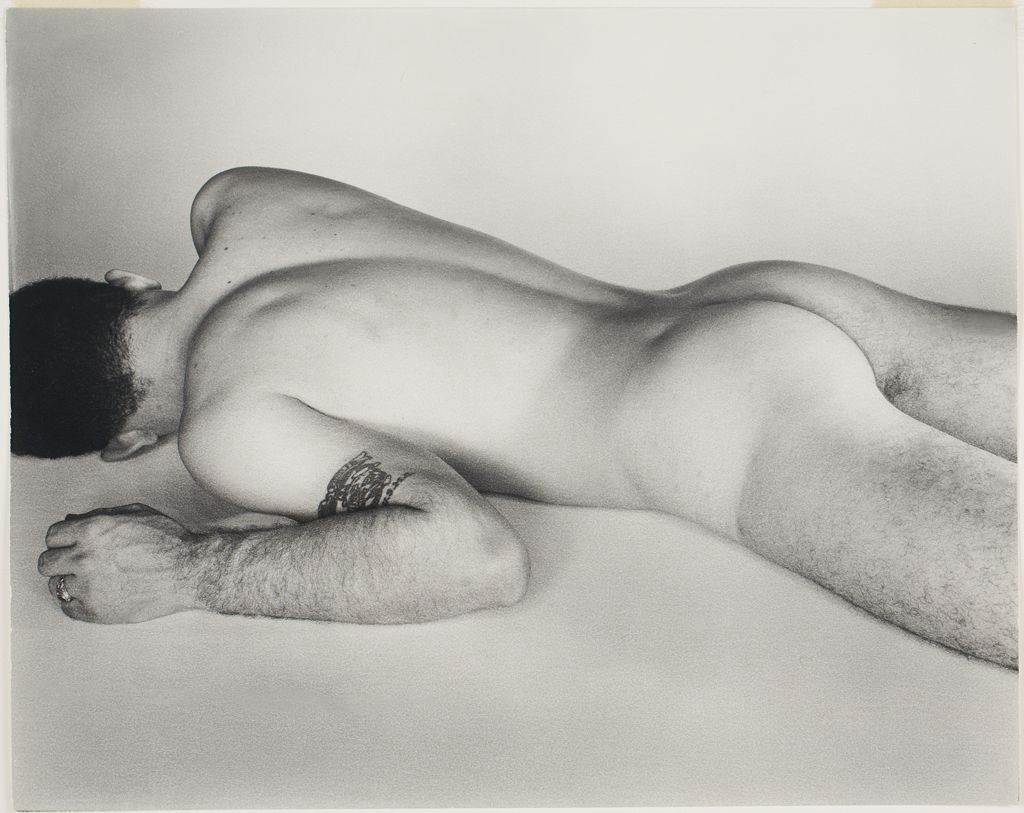

By the early 1930s, Lynes had begun producing a series of male nudes that blended classical influences—Greek sculpture, Renaissance painting—with the sleek modernism of Art Deco. Unlike typical academic nudes, Lynes’s subjects were not anonymous muses but men with whom he shared personal and often romantic bonds. These photographs, which captured beauty, vulnerability, and homoerotic longing, could not be exhibited openly. Instead, Lynes circulated them privately among his queer kinship networks.

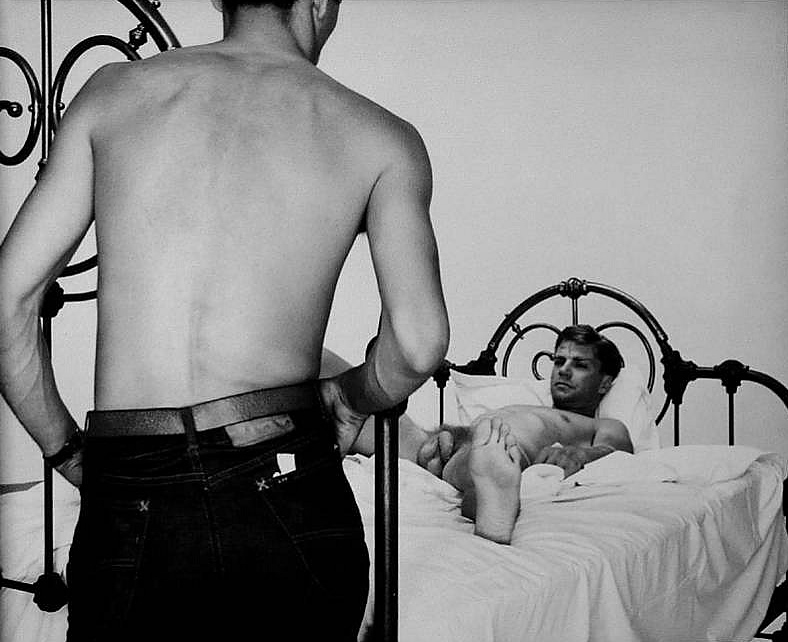

Lynes was part of a closely connected circle of elite gay men who shaped American arts and letters between the world wars and into the early Cold War. For sixteen years, Lynes lived with writer Glenway Wescott and museum curator Monroe Wheeler, who were a couple for over fifty years. The three shared a household, with Lynes and Wheeler sharing a bedroom. This network extended to other prominent cultural figures, including Lincoln Kirstein and artist Paul Cadmus. During the 1940s and early 1950s, they hosted private gatherings and sex parties, creating a vibrant yet discreet sexual subculture. However, as Cold War paranoia intensified, especially targeting homosexuals, these communities were forced further underground.

In April 1950, Wescott voiced his concerns to Lynes about the risks of circulating explicit photographs. While he personally supported Lynes’s art, he feared professional repercussions for Wheeler, who by then held a prominent public role at the Museum of Modern Art. Wescott warned of the dangers of “guilt by association,” especially given the rising visibility of anti-communist and anti-homosexual purges in government and cultural institutions. His fears were justified. On March 1, 1950, The New York Times reported that of ninety-one State Department employees forced to resign under loyalty investigations, “most of these were homosexuals.” Though the article framed this in the context of communist infiltration, it was clear that sexual orientation had become a major front in the Cold War cultural wars.

Despite the risks, Lynes continued to make and circulate his portraits. Determined that his work would find an audience, he published some images in the German homosexual journal Der Kreis during the 1950s, one of the few outlets at the time willing to feature such material. He also became an important collaborator with Alfred Kinsey, the pioneering sex researcher. Between 1949 and 1955, Lynes sold and donated a significant portion of his male nudes to Kinsey’s research institute. This ensured that even if the public could not yet see these works, they would be preserved. Today, much of Lynes’s homoerotic photography resides at the Kinsey Institute in Bloomington, Indiana.

Lynes’s photographs are not only striking in their formal beauty and symbolism but also powerful cultural documents. They archive queer, illicit desire at a time when being openly homosexual could mean career destruction, social ostracism, or worse. His images captured the bodies and souls of men who, like himself, lived in defiance of rigid moral codes and the oppressive climate of McCarthy-era America. The fact that he continued this work privately, even as the Red Scare and Lavender Scare drove many into deeper secrecy, speaks to his artistic courage and personal integrity.

George Platt Lynes died of lung cancer in 1955 at the age of 48. While much of his work was nearly lost—he destroyed many negatives fearing posthumous exposure—his decision to entrust photographs to Kinsey safeguarded his legacy. Today, George Platt Lynes is recognized not only for his contributions to fashion and portrait photography but as a courageous, visionary artist who captured the complexities of queer male identity long before the modern gay rights movement. His private images, once kept in the shadows, now illuminate a vital chapter of both photographic and LGBTQ+ history.