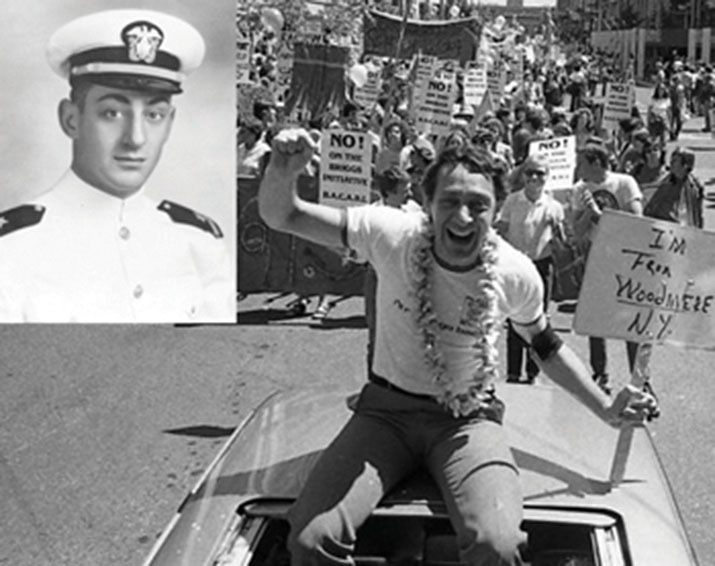

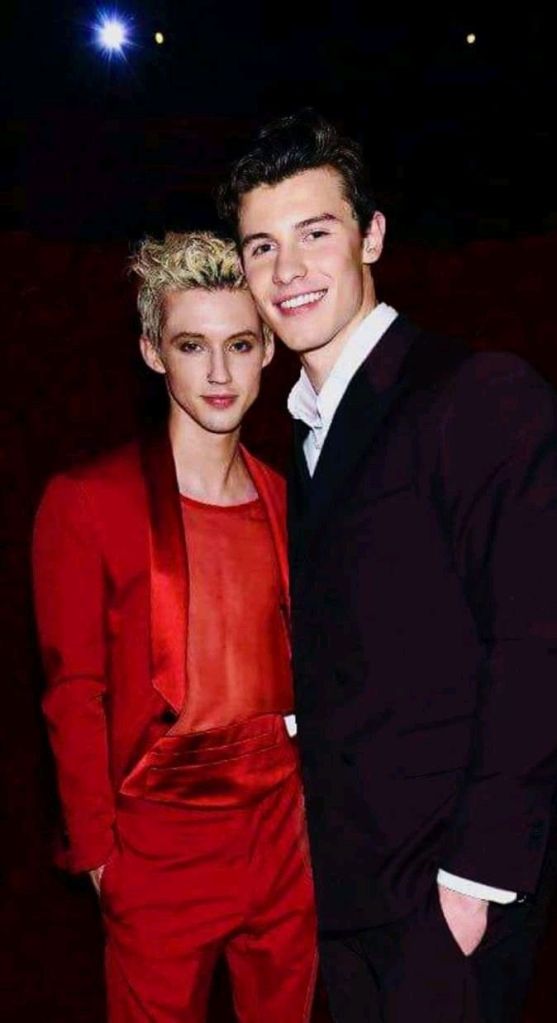

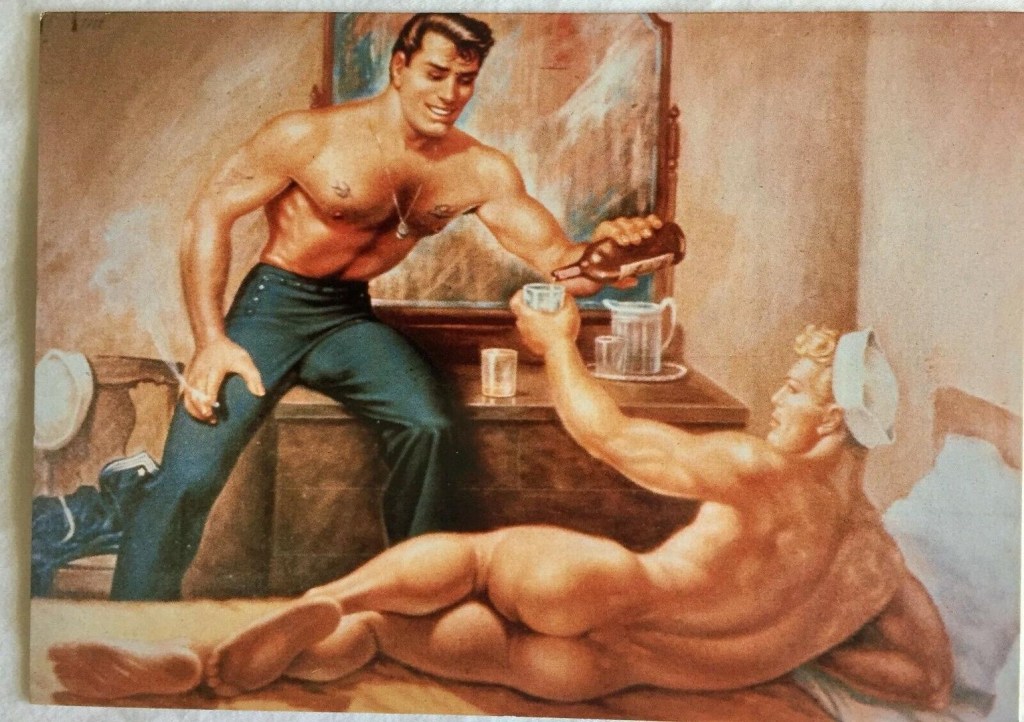

When the first Pride parade marched through New York City in June 1970—commemorating the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall uprising—it marked not only a political turning point but also an artistic awakening. No longer confined to coded symbolism or covert expression, gay pride began to blaze through the art world in bold, unflinching forms. Over the next six decades, LGBTQ+ artists harnessed the power of visibility to challenge oppression, celebrate desire, mourn loss, and imagine futures beyond shame.

The 1970s: Visibility and Liberation

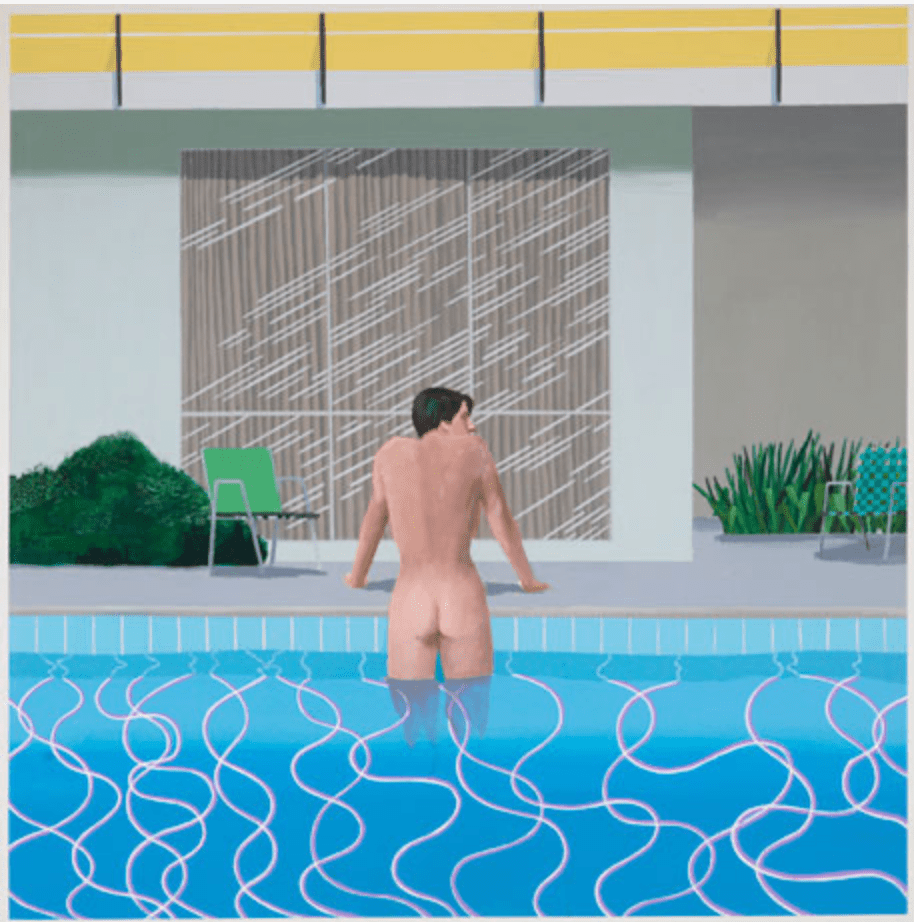

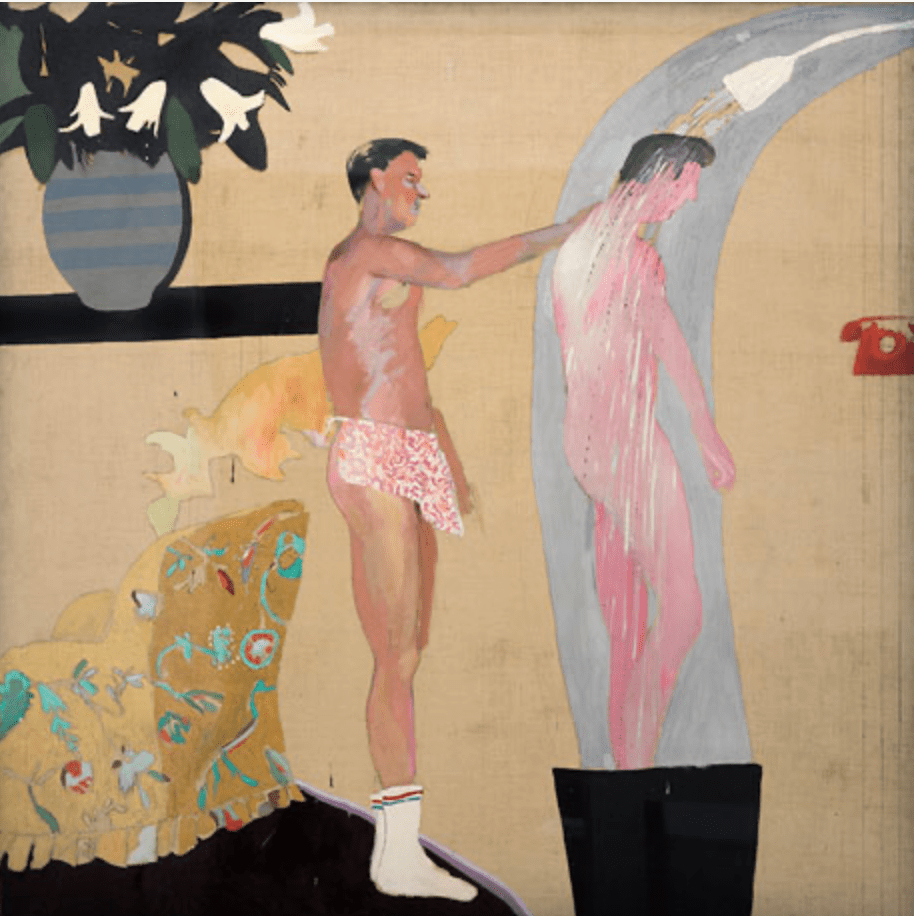

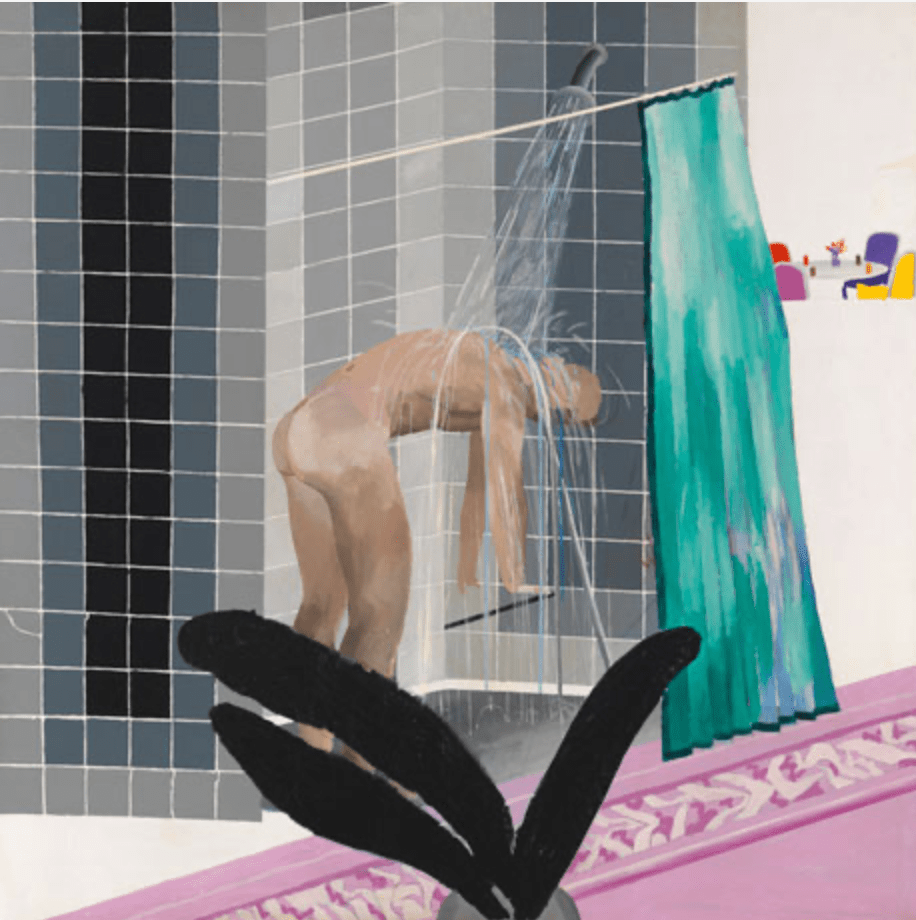

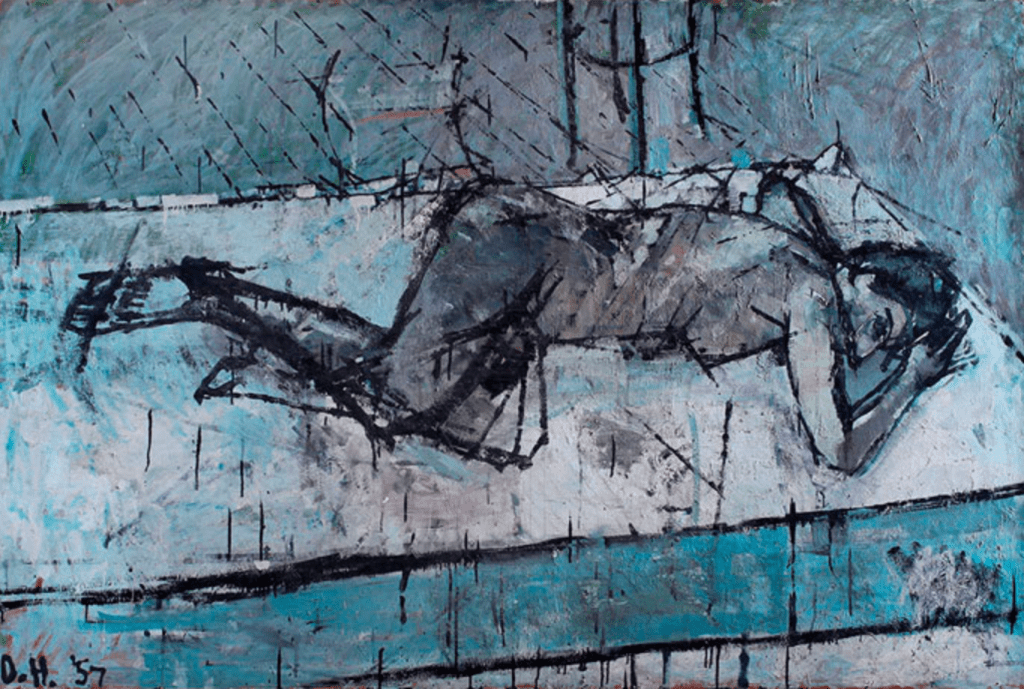

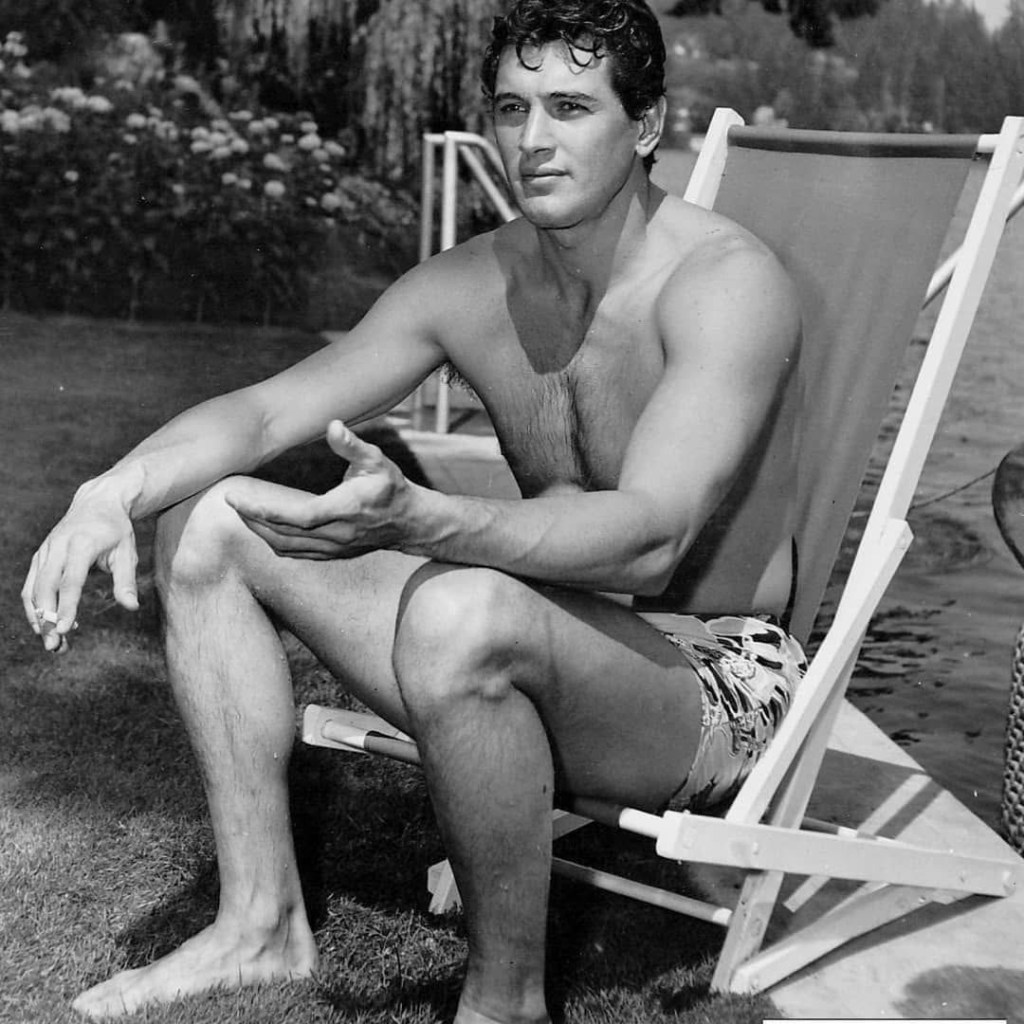

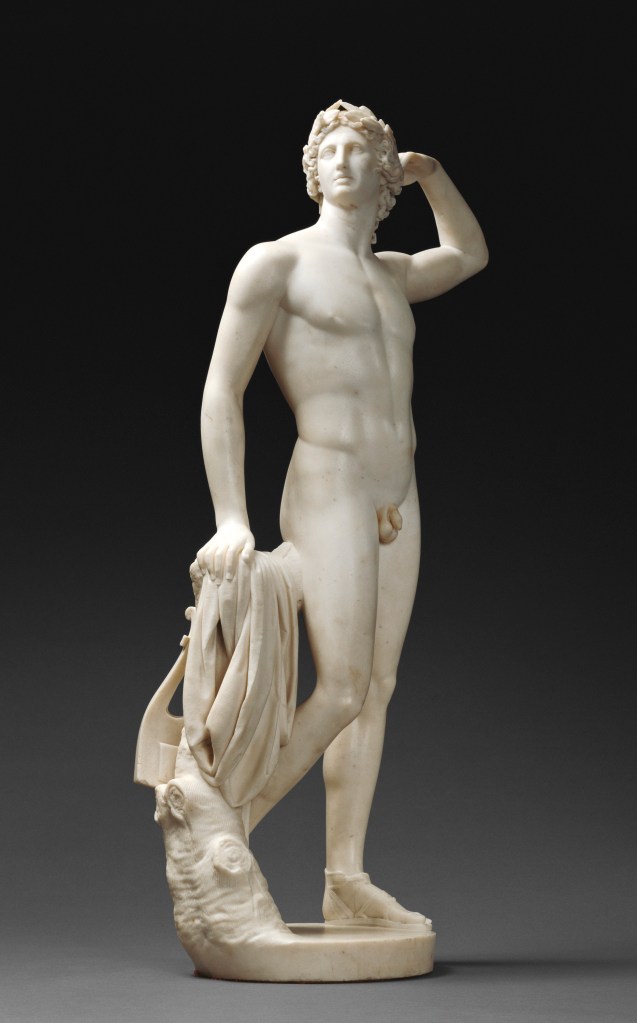

Hockney is known for his vibrant use of color, innovative techniques, and significant contributions to the Pop Art movement. He infused his work with subtle but powerful depictions of gay male intimacy. His 1971 painting Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) captured not just a sunlit pool but a relationship dynamic—gaze, distance, vulnerability. It remains one of the most iconic queer paintings of the 20th century. Educated at the Royal College of Art in London, Hockney became celebrated for his depictions of California life, especially his swimming pool series such as Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool (1966). His artistic practice spans painting, drawing, printmaking, photography, stage design, and digital art, including pioneering work with iPad drawing apps. Openly gay, Hockney’s works often explore themes of intimacy, domestic life, and sexuality, and his expansive career has solidified him as one of the most influential artists of the 20th and 21st centuries.

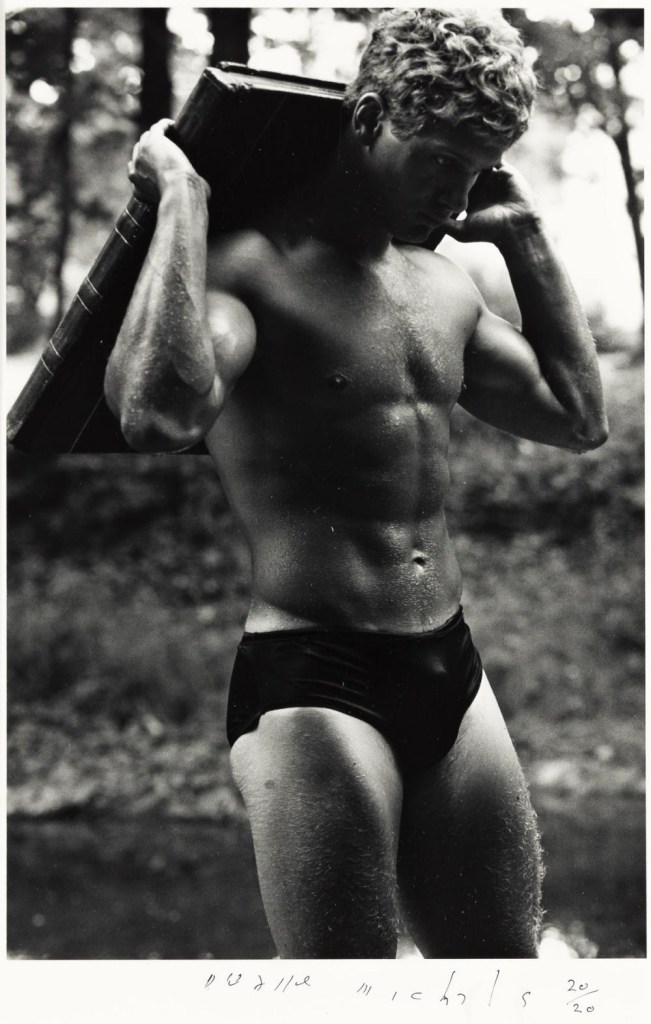

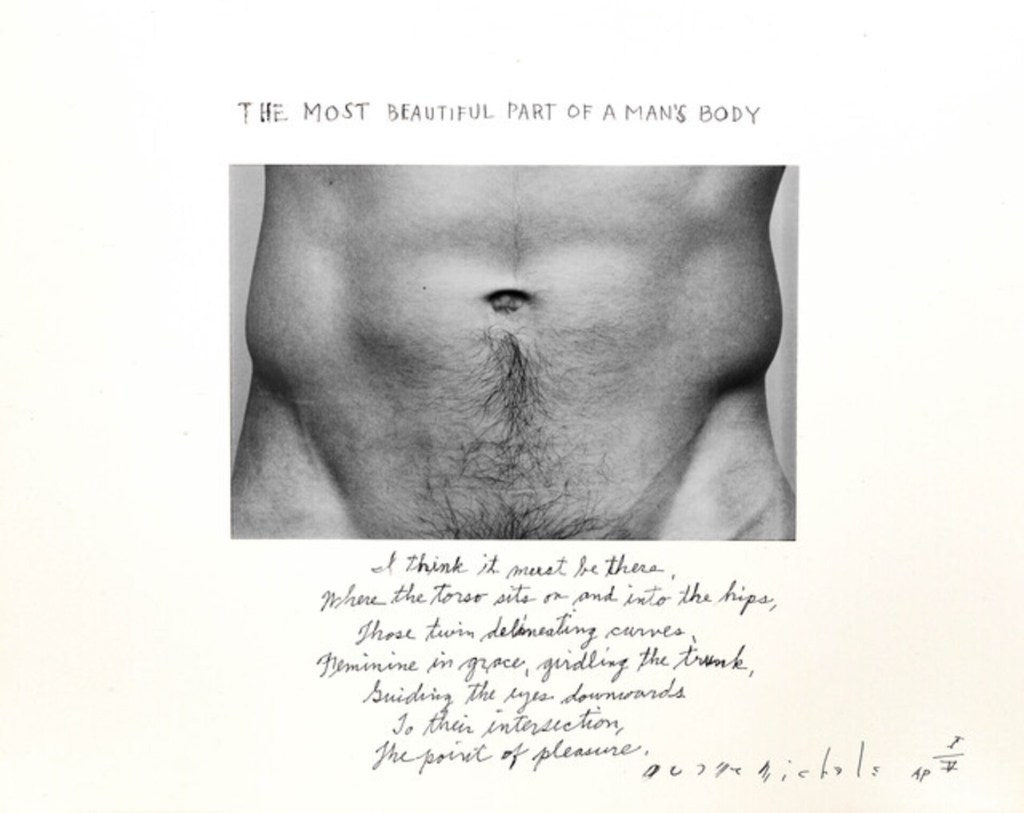

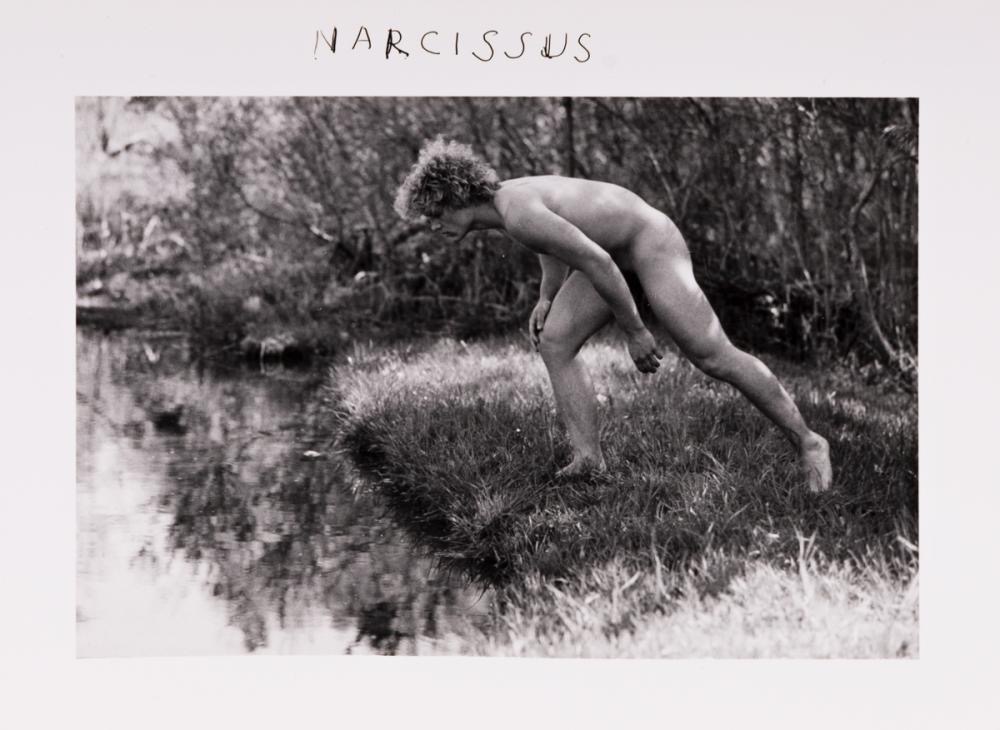

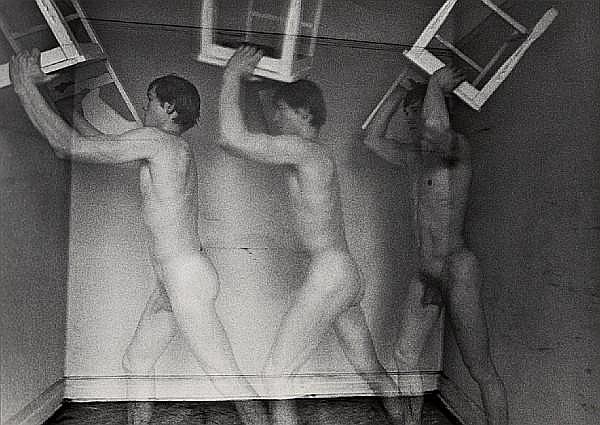

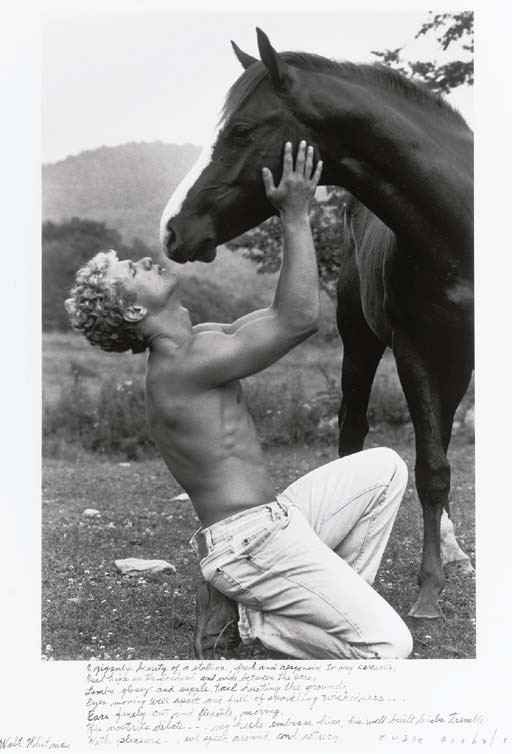

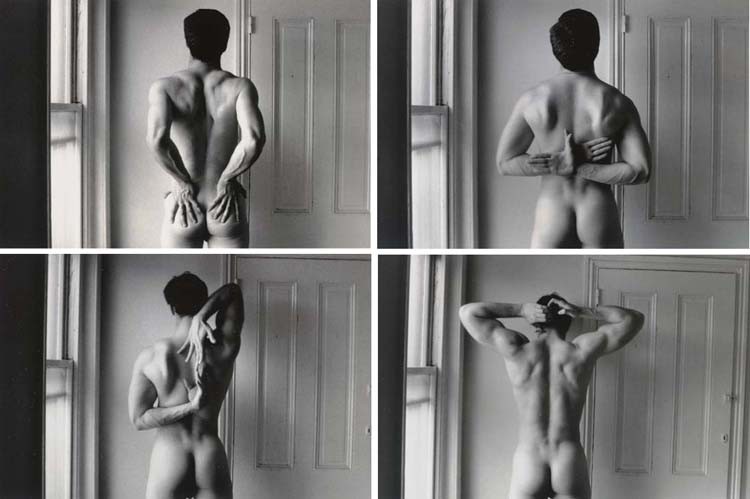

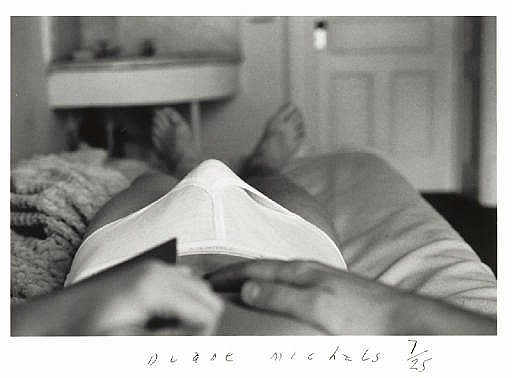

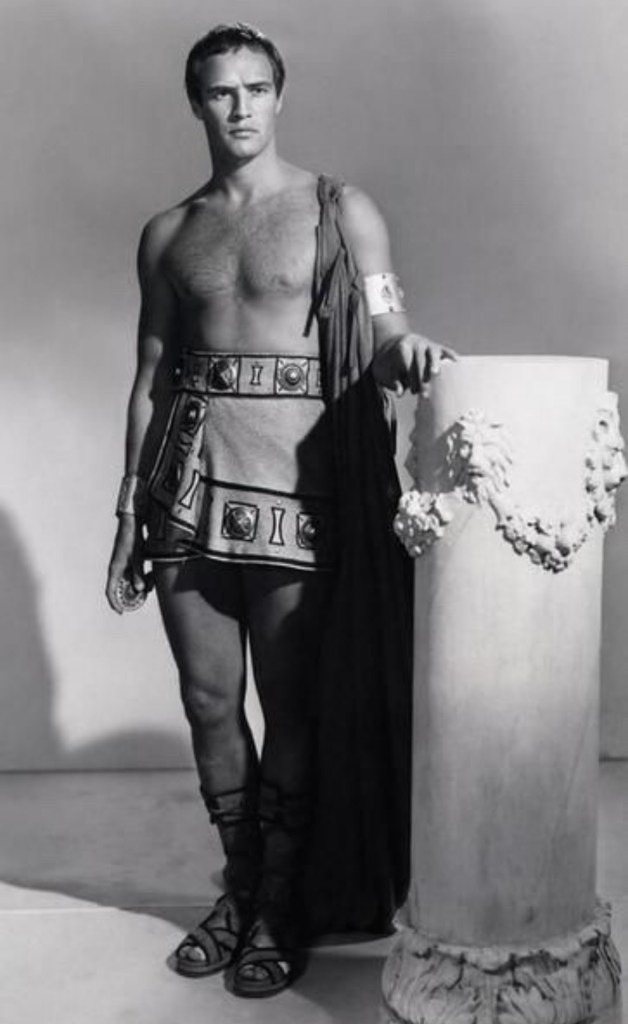

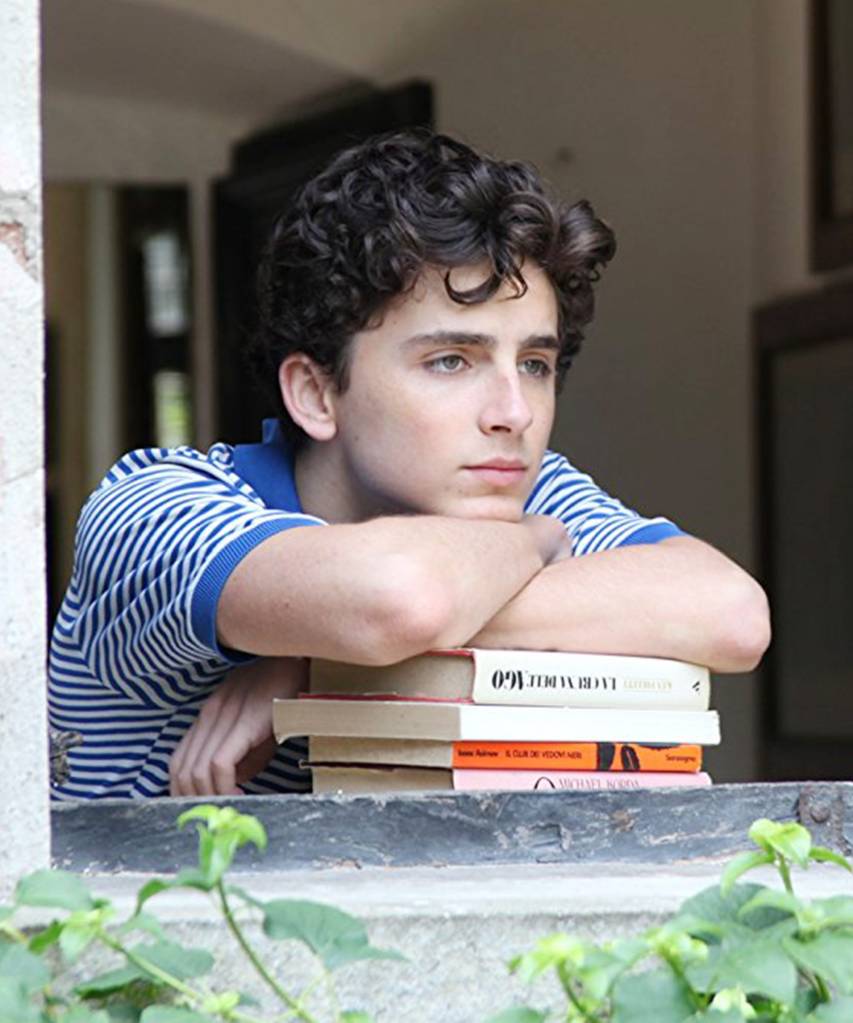

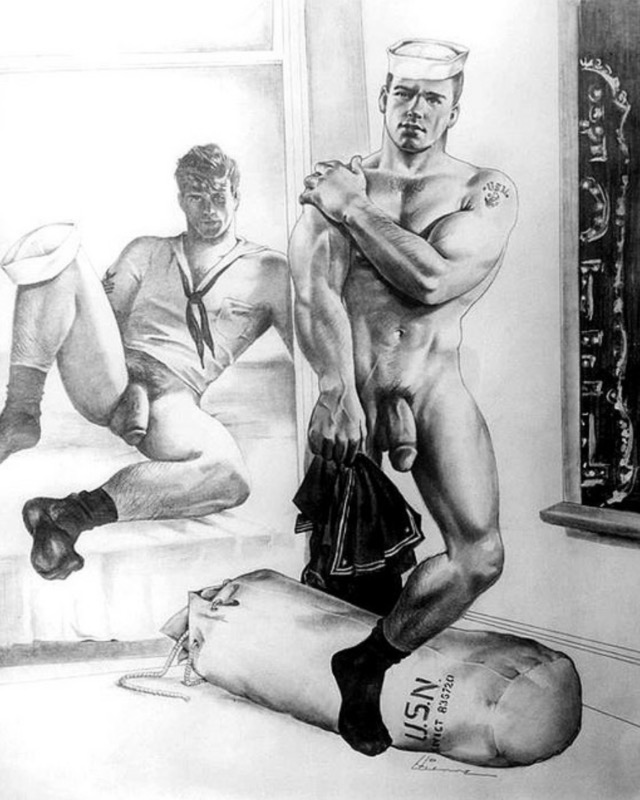

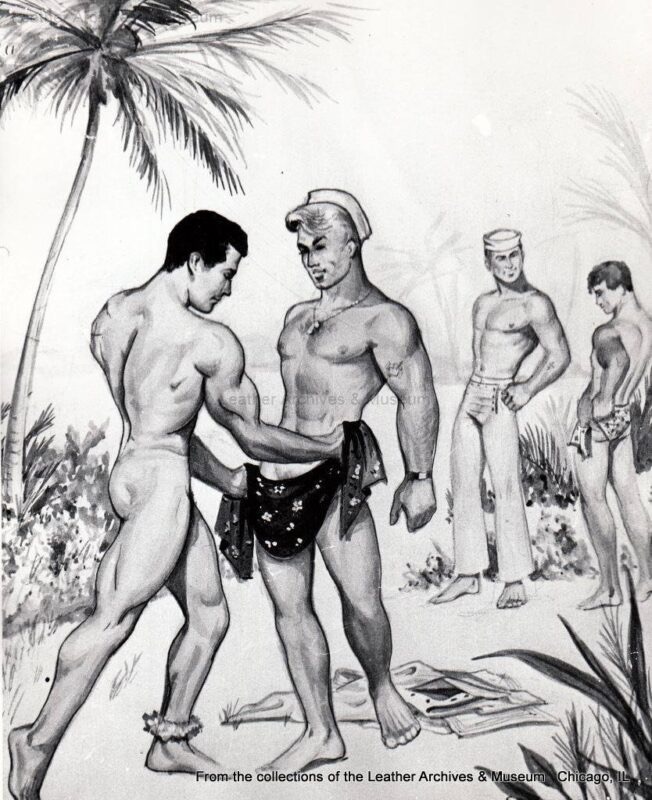

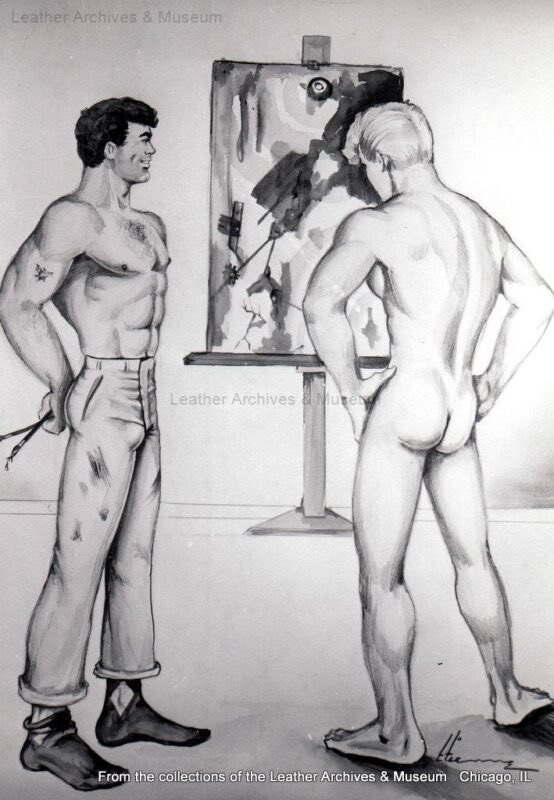

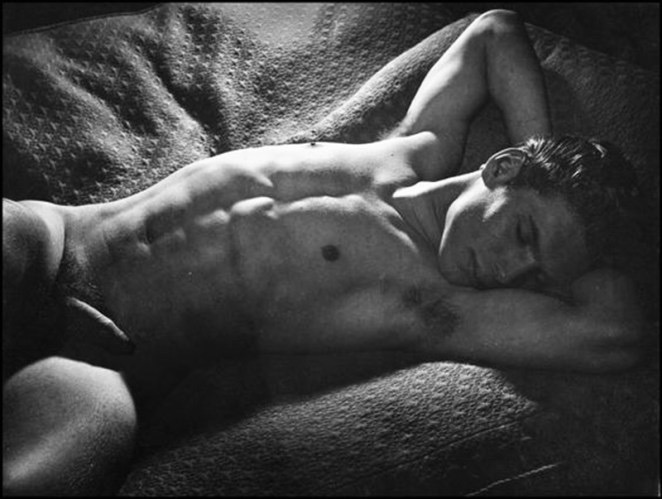

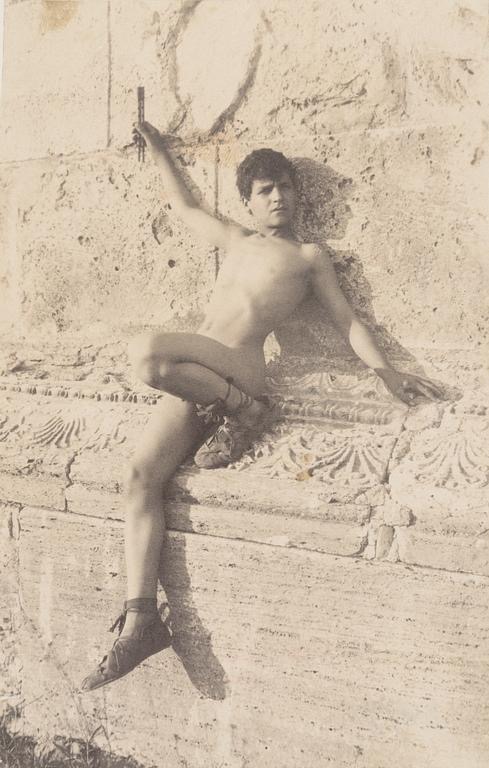

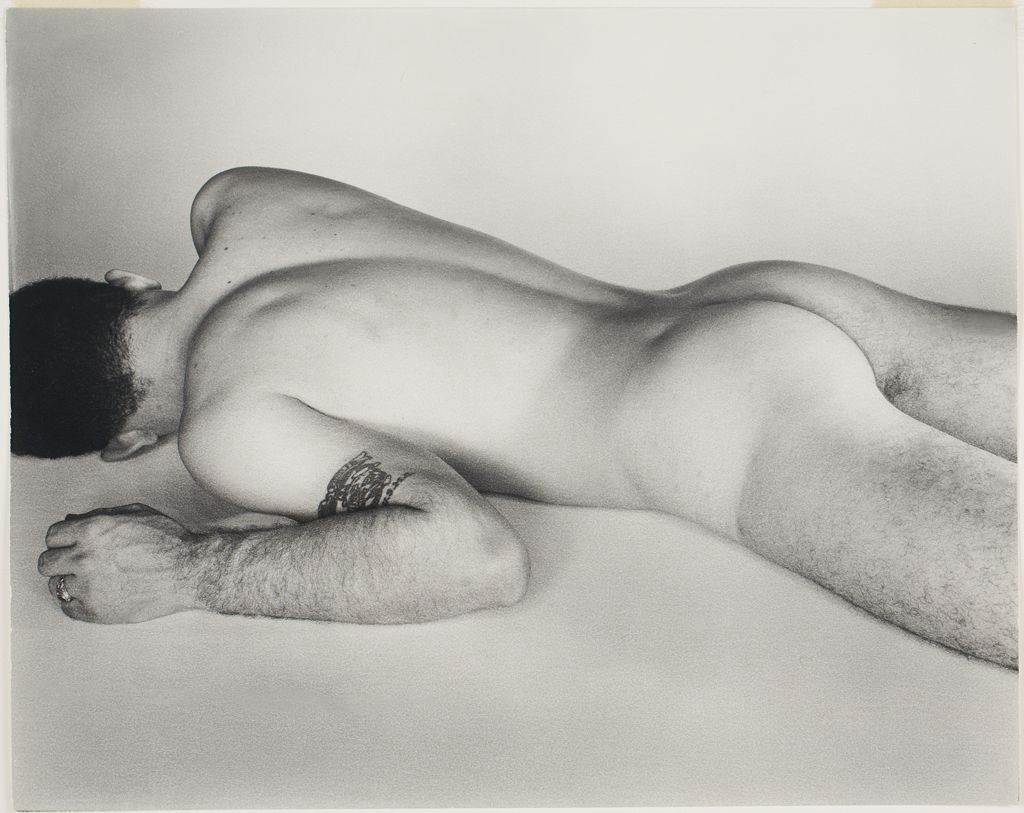

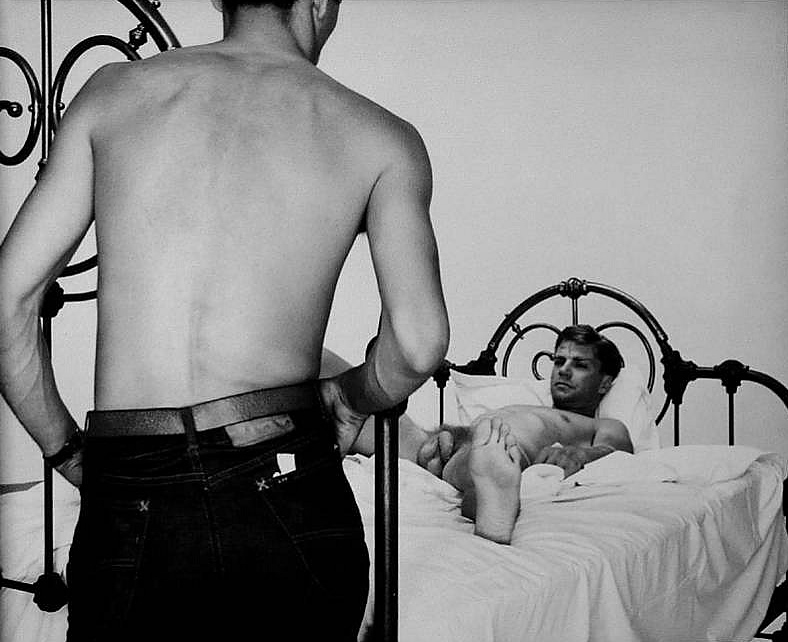

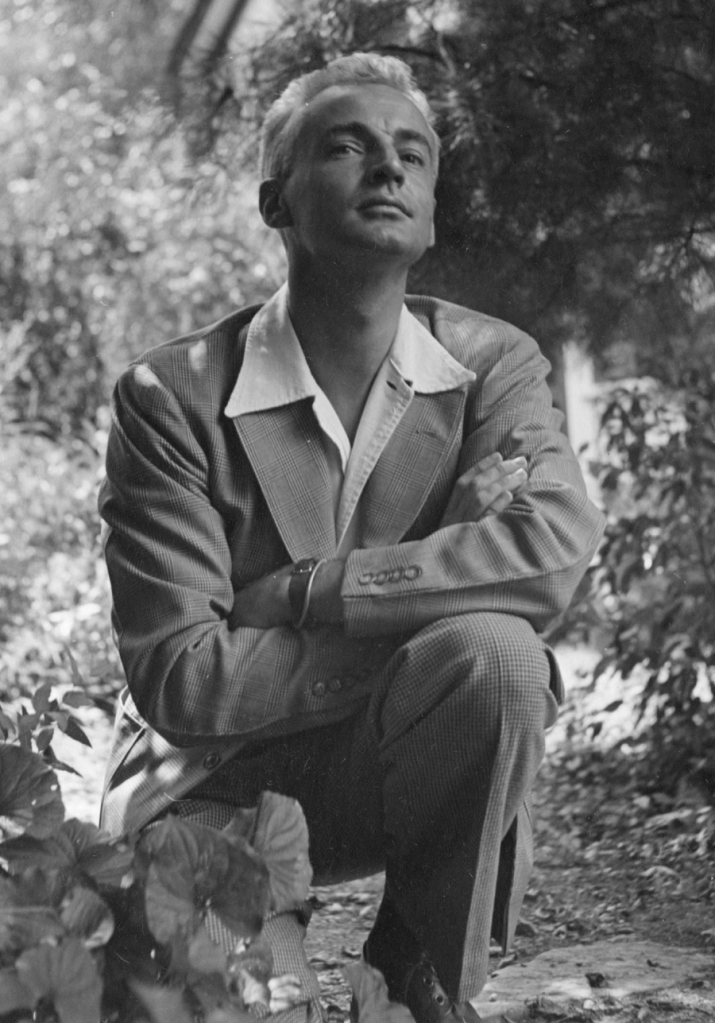

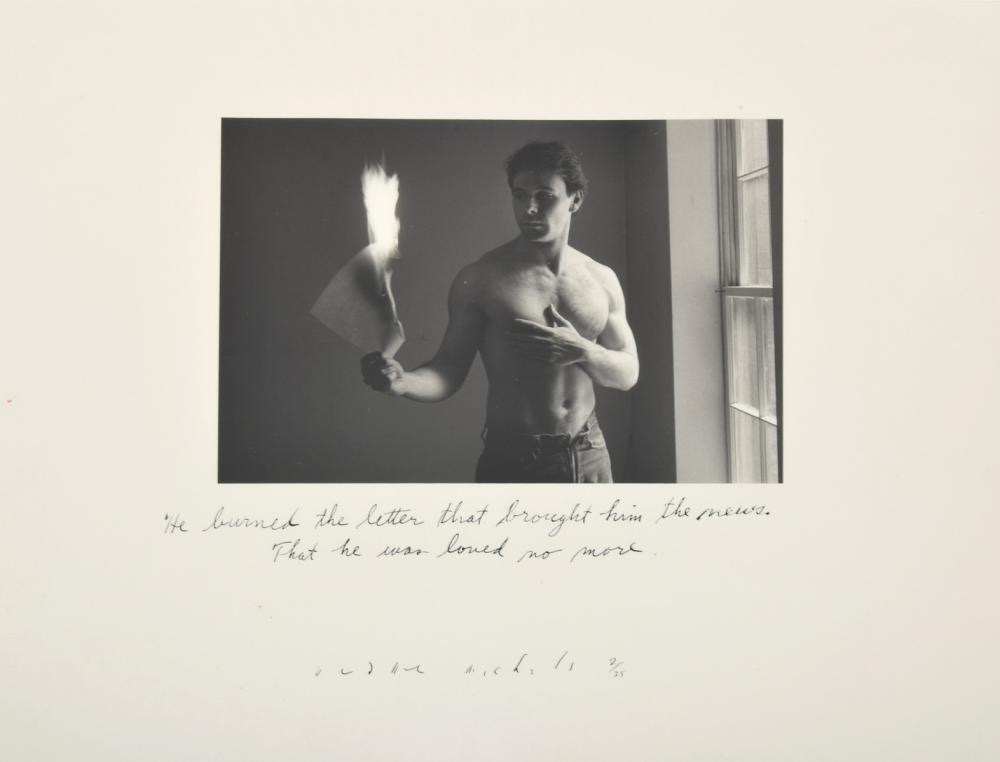

Duane Michals (1932- ) is an influential American photographer renowned for his innovative use of photographic sequences and handwritten narratives that create intimate and poetic visual storytelling. Often blending dream-like imagery with deeply personal themes, Michals pushed beyond traditional documentary photography, favoring staged scenes to explore metaphysical questions, mortality, and human emotion. He used photographic sequences to tell poetic, often erotic, visual stories—like his haunting piece The Most Beautiful Part of a Man’s Body (1974), which explored vulnerability and sensuality through layered narrative. Michals’ pioneering approach profoundly impacted contemporary photography, emphasizing that imagery could embody not only what is seen, but also what is felt, imagined, or deeply desired.

The 1980s–90s: Art in the Shadow of AIDS

As the AIDS crisis devastated the LGBTQ+ community, artists responded with fury, grief, and resilience.

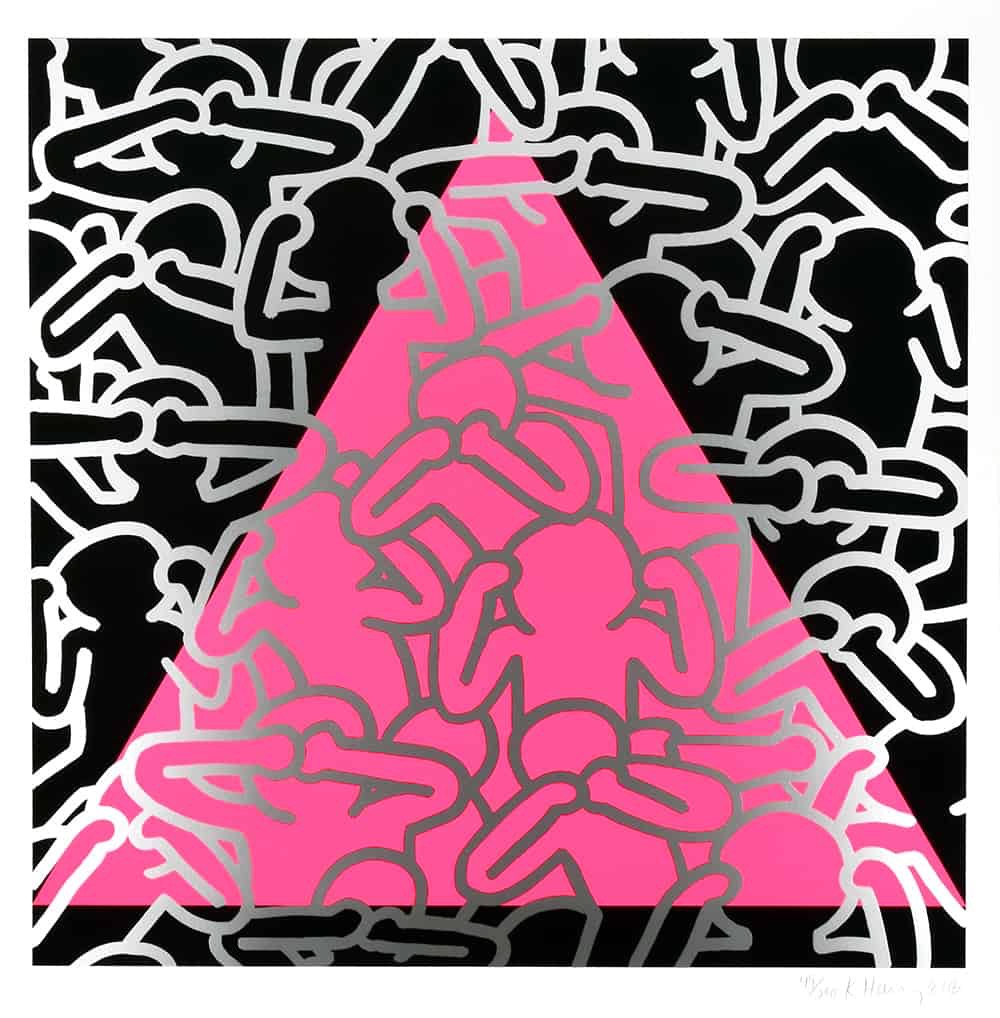

Keith Haring (1958-1990) was a groundbreaking American artist whose bold, neon-outlined figures transformed urban spaces and gallery walls into vibrant canvases filled with queer joy and political urgency. Rising to prominence in the 1980s New York art scene, Haring used accessible imagery and public spaces—including subways and street murals—to communicate powerful messages on sexuality, AIDS awareness, and social justice. His iconic Silence = Death imagery became a rallying cry against apathy and inaction, galvanizing activism during the AIDS epidemic and amplifying voices within the LGBTQ+ community. Haring’s energetic style and activist spirit continue to resonate, ensuring his legacy as an artist who merged exuberant creativity with fearless advocacy.

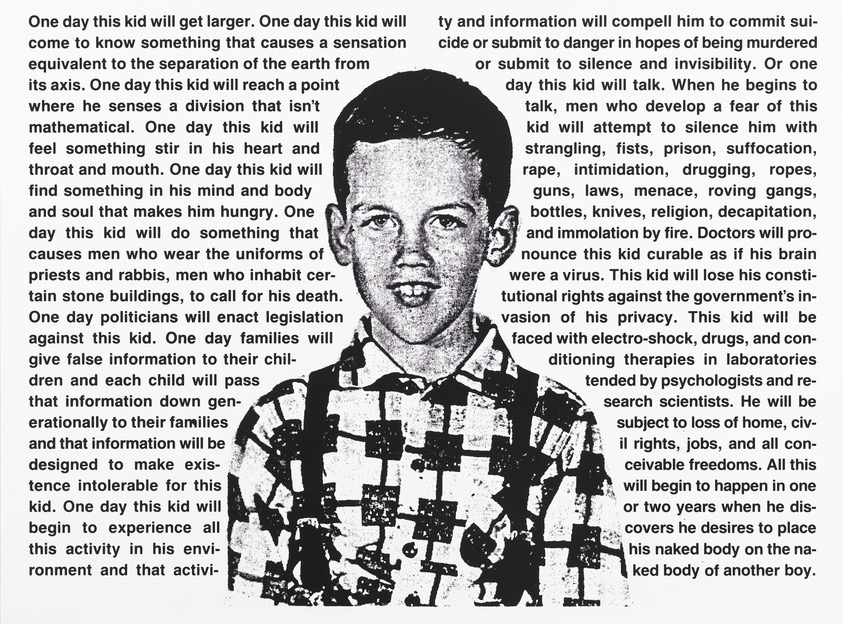

David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) was a fiercely confrontational American artist, writer, and activist whose work channeled the raw power of queer rage into searing critiques of homophobia, censorship, and government inaction during the AIDS crisis. Emerging from New York’s East Village art scene in the 1980s, Wojnarowicz worked across media—painting, photography, film, and text—to expose the violence and vulnerability of queer existence. His iconic piece Untitled (One day this kid…) (1990) juxtaposes a childhood photo of himself with a prophetic, damning text that lays bare the grim realities faced by queer youth in a hostile world. Unapologetically political and deeply personal, Wojnarowicz’s art remains a visceral reminder of both the pain and defiance at the heart of queer survival.

The NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, begun in 1987, now contains over 50,000 panels. It is both a work of art and a massive, tangible act of remembrance and protest.

2000s–Present: Intersectionality and Expanding the Frame

In recent decades, Pride in art has become more expansive, intersectional, and experimental.

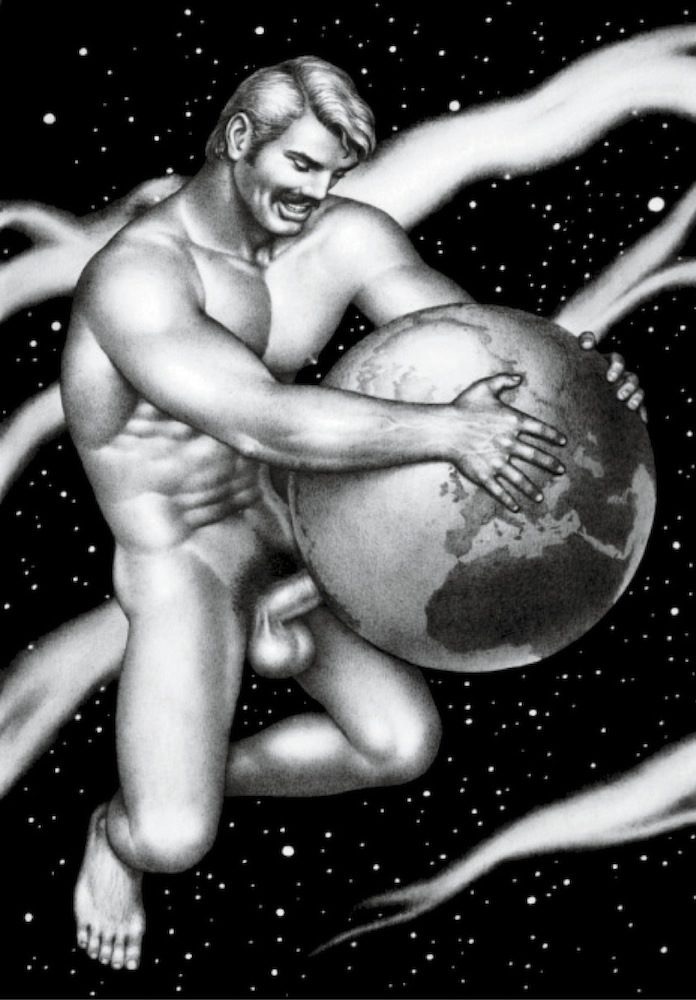

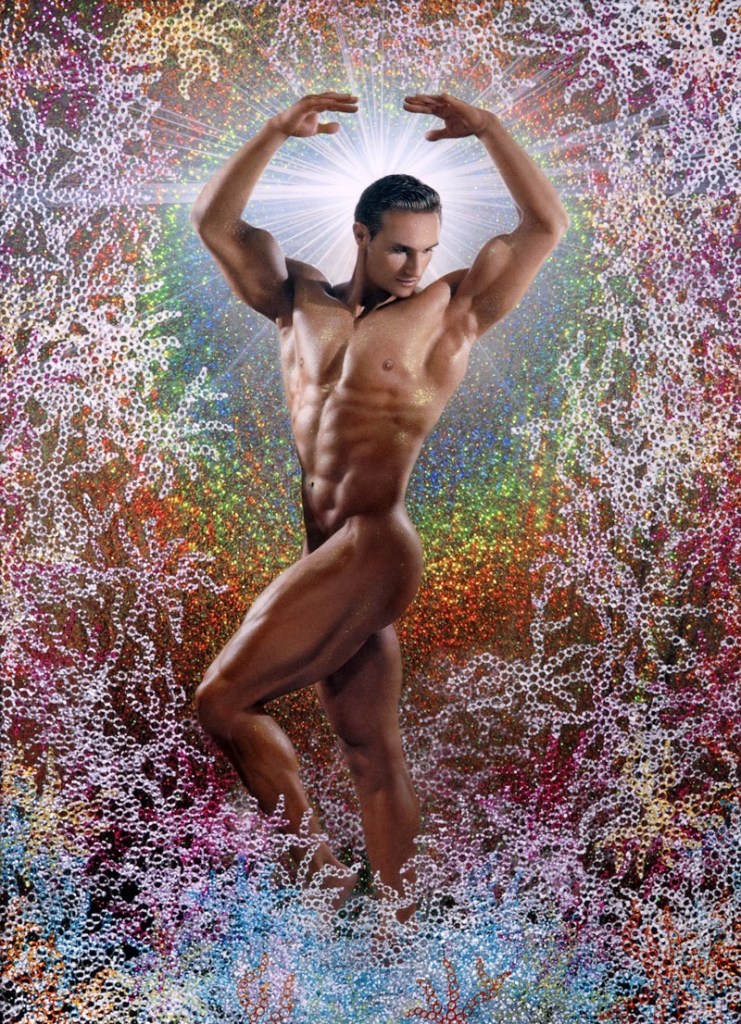

Zanele Muholi, a South African visual activist, documents Black LGBTQ+ life through dramatic portraiture. Their series Faces and Phases offers a powerful visual archive of queer resilience. Mickalene Thomas reclaims the Black female body in rhinestone-studded paintings and photographic tableaux. Her work unapologetically fuses queerness, glamour, and political assertion. See Le déjeuner sur l’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires (2010), a reimagining of Manet’s painting through a queer, Black feminist lens. Cassils, a transgender performance artist, uses their body in durational, often physically intense works. In Becoming an Image, they strike a clay block in darkness while a camera flash records the violence—a metaphor for queer visibility and embodiment. Juliana Huxtable, a Black trans artist, poet, and performer, combines Afrofuturism, photography, and digital media to challenge fixed identities. Her self-portraits—gender-fluid, mythic, fierce—embody queer futurity.

More Artists to Explore

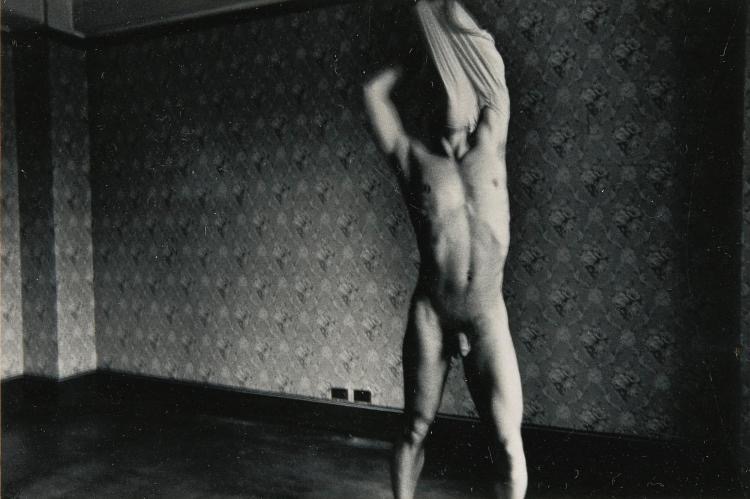

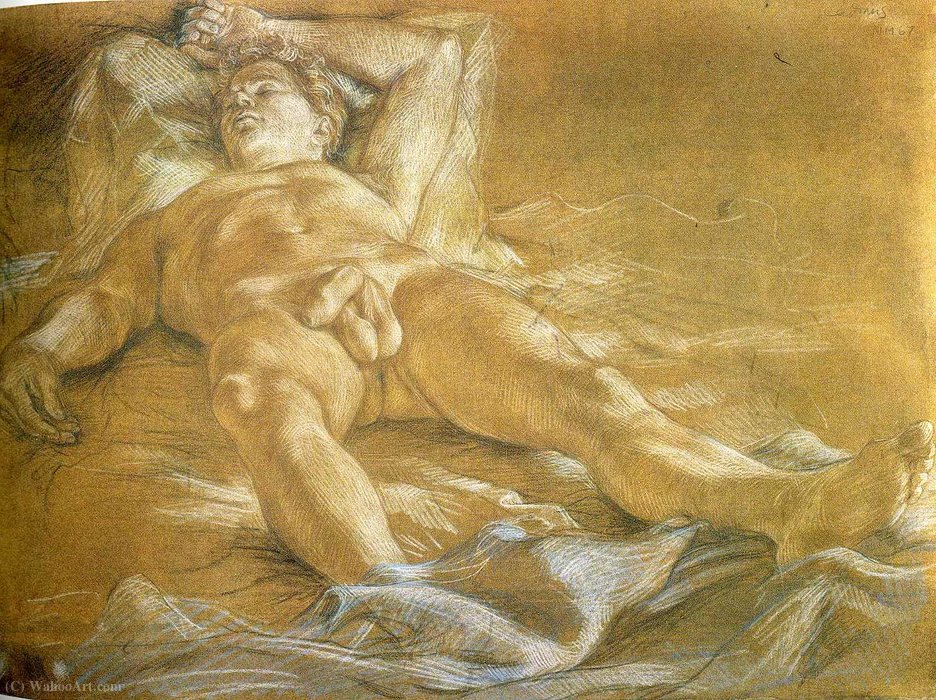

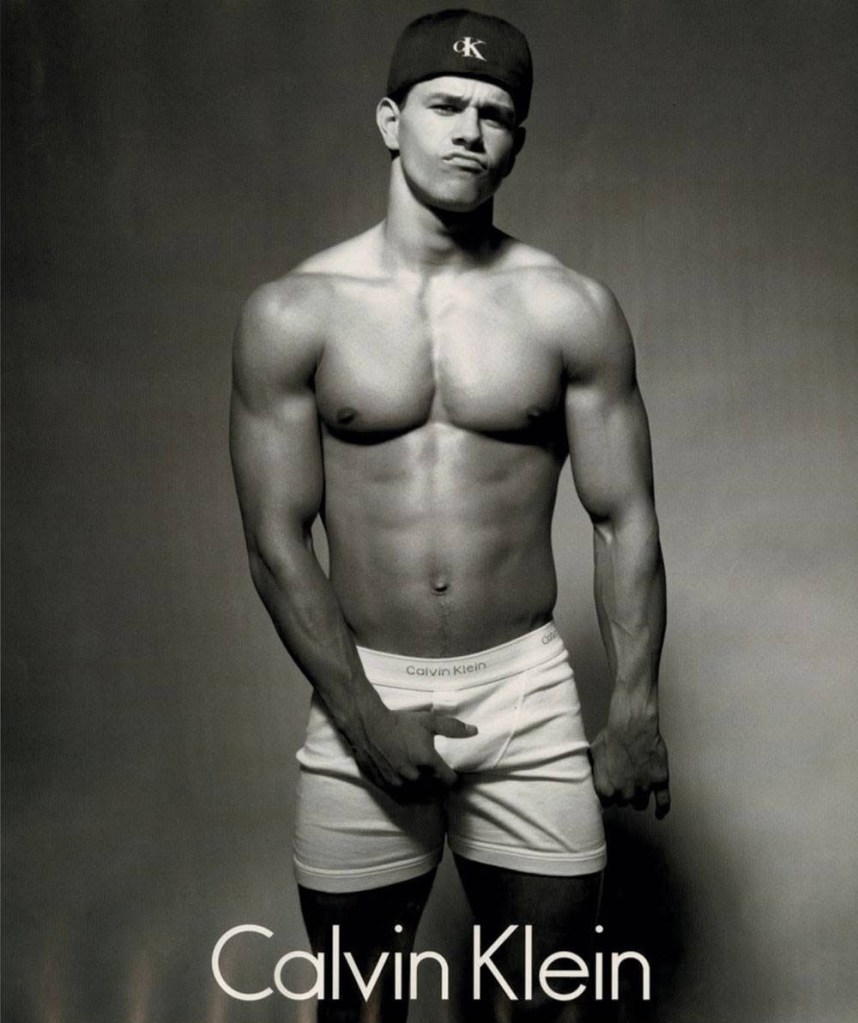

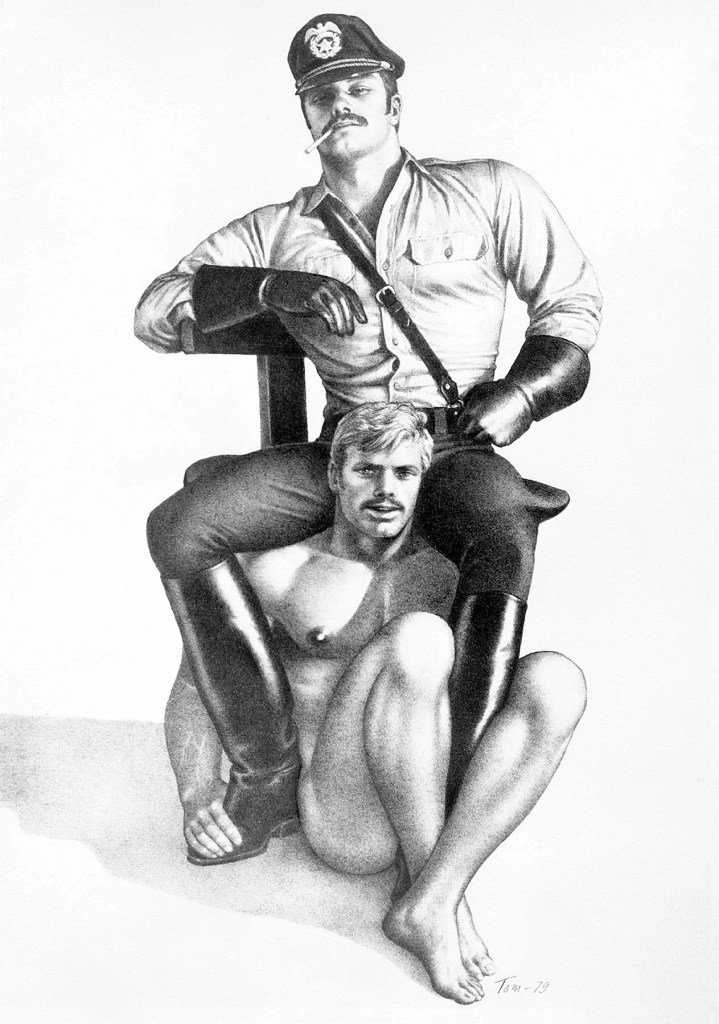

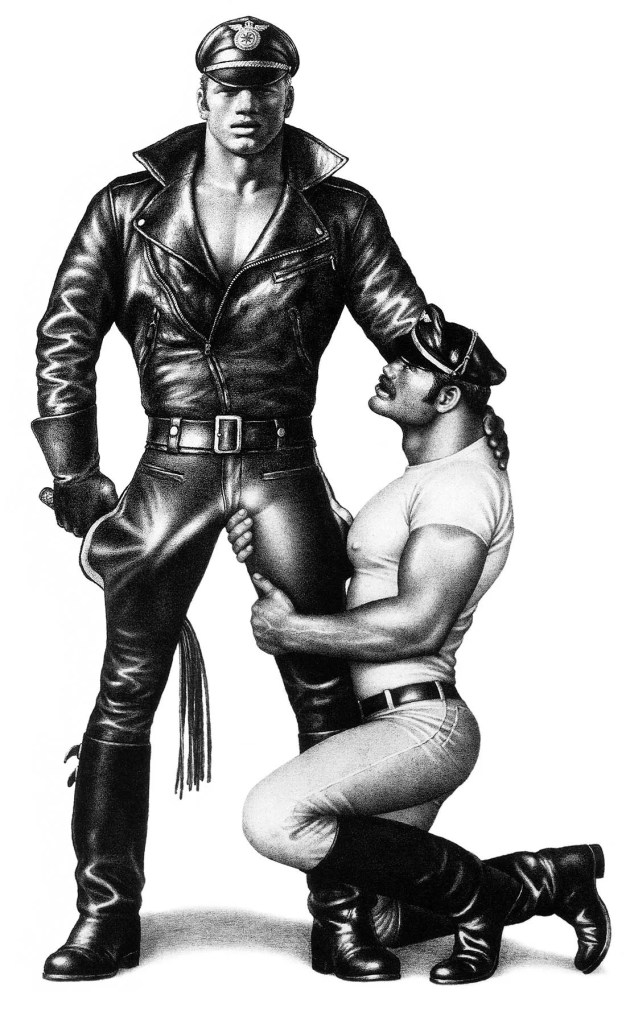

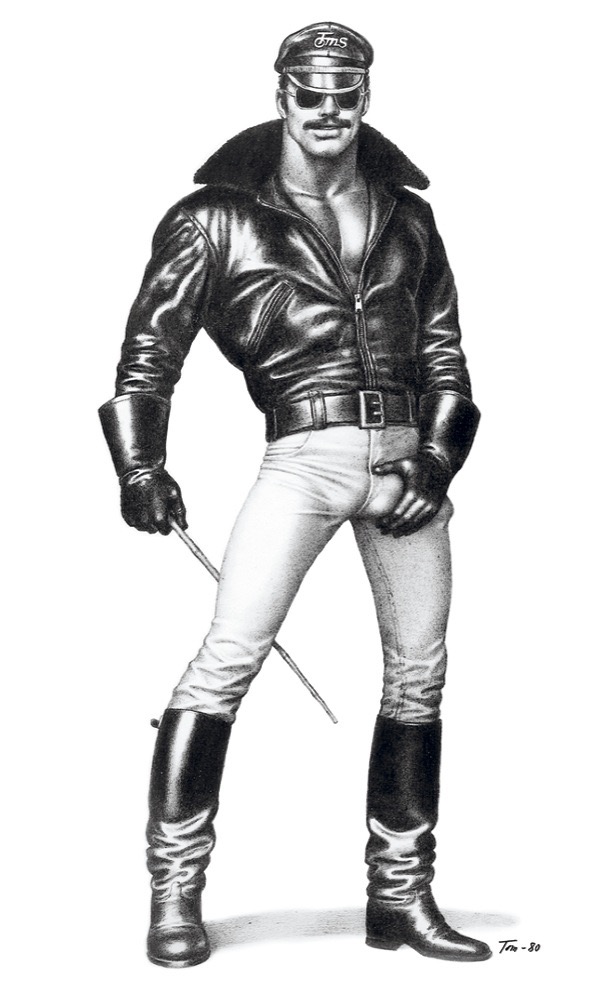

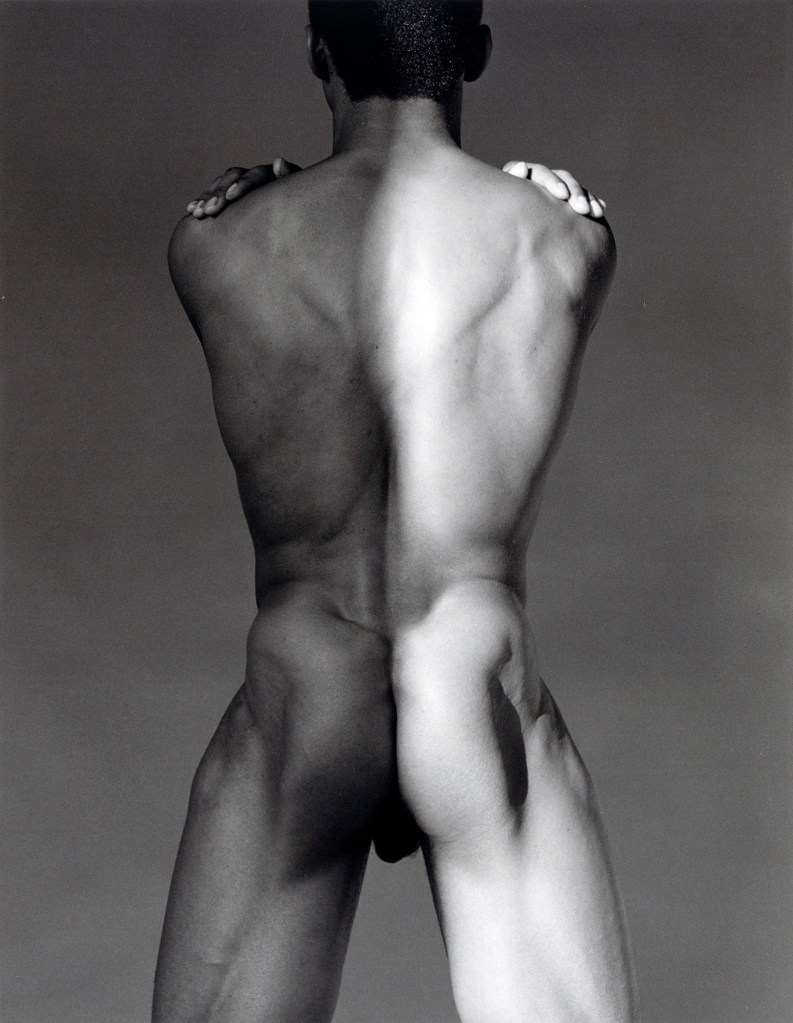

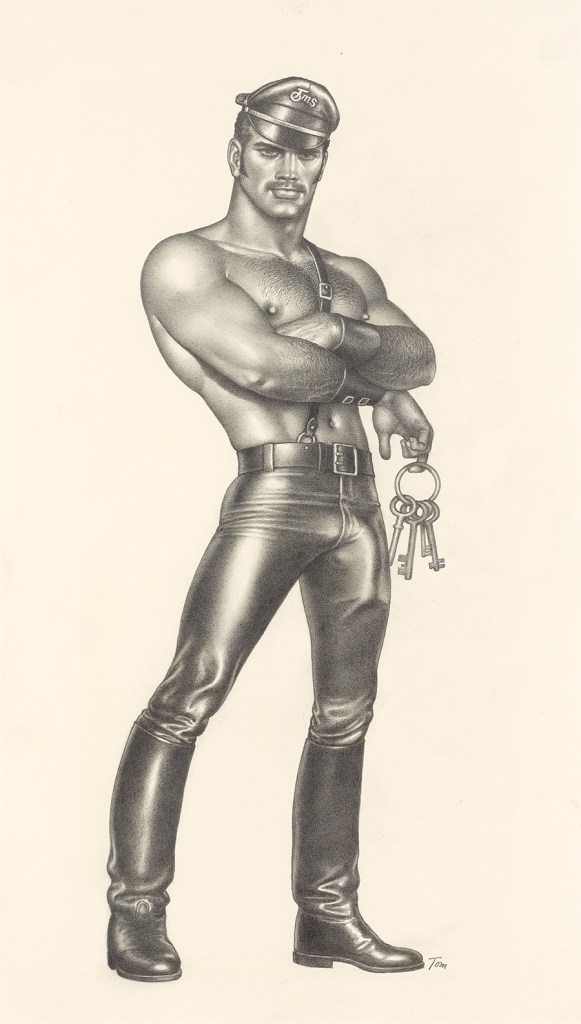

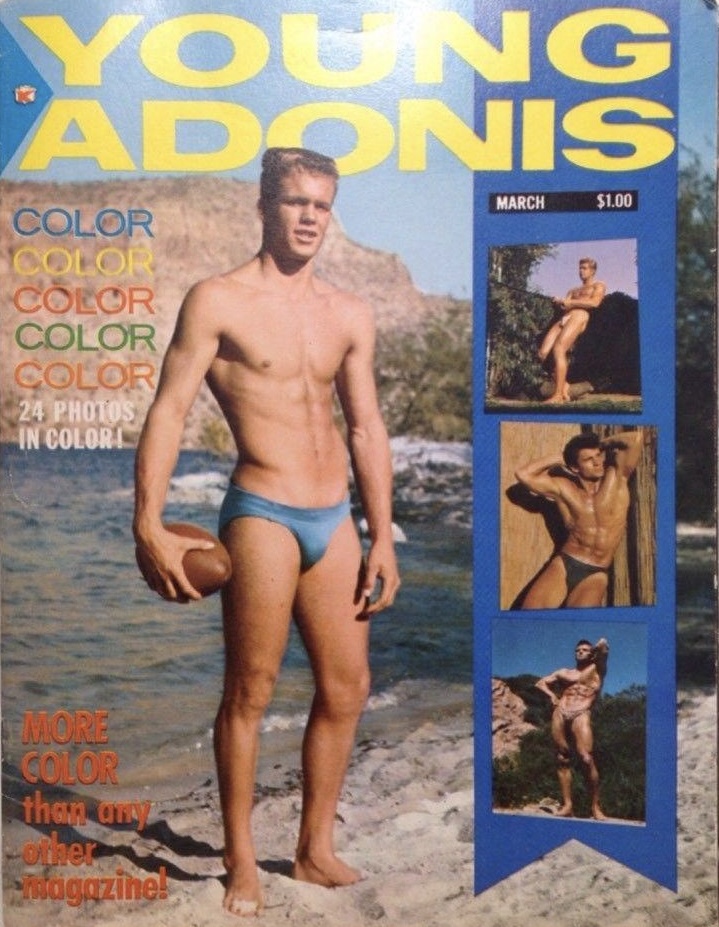

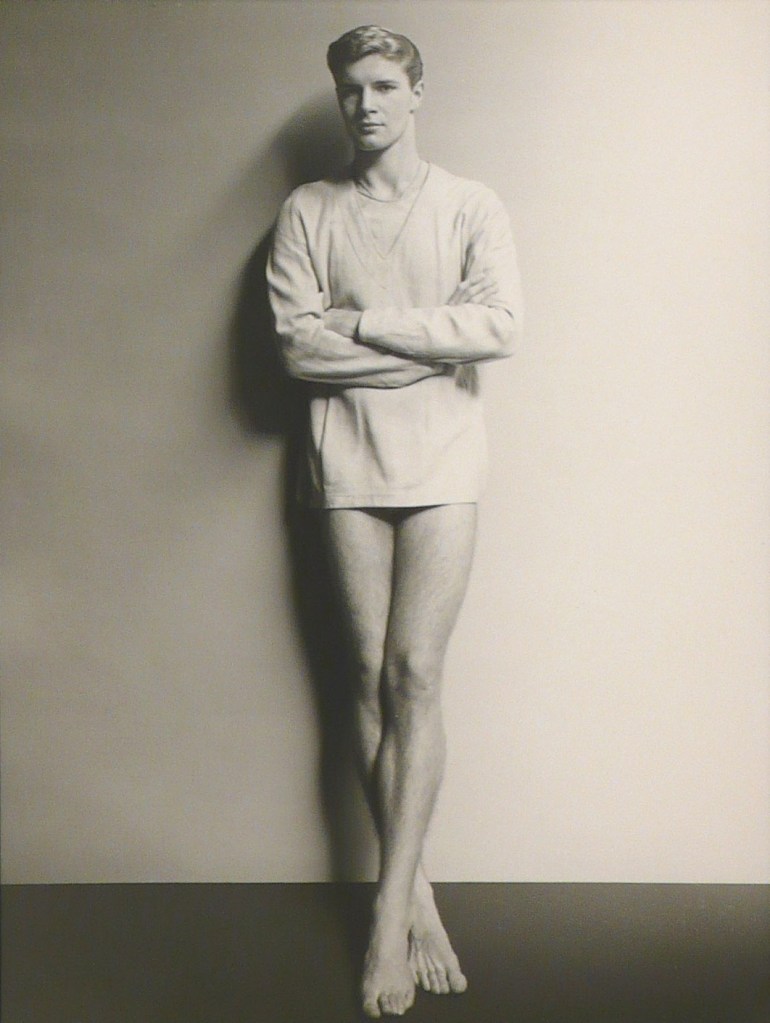

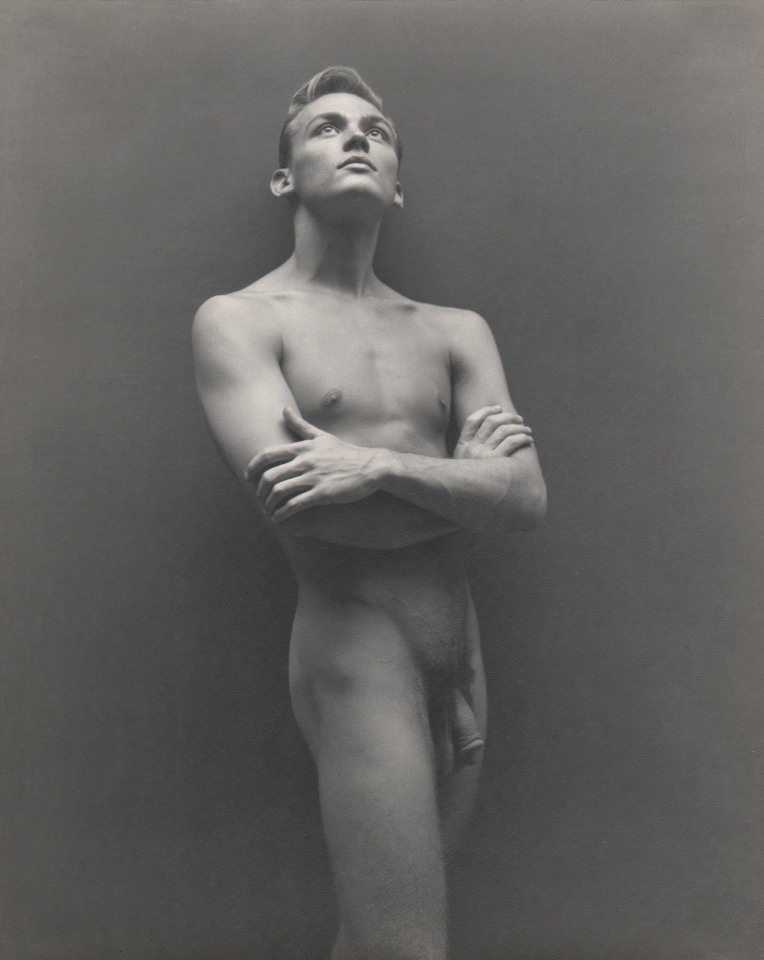

- Robert Mapplethorpe – his black-and-white male nudes remain some of the most iconic (and controversial) queer images in American photography.

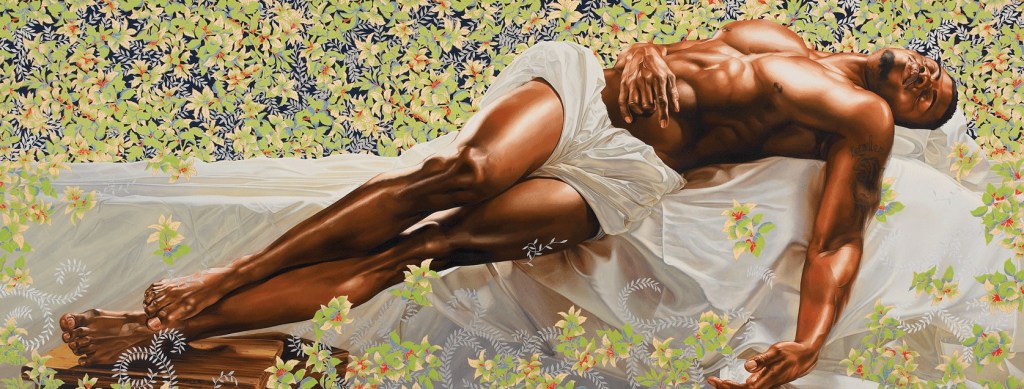

- Kehinde Wiley – while not exclusively queer-themed, his work often presents Black men in romantic or intimate poses, reclaiming both history and homoerotic aesthetic.

- Hunter Reynolds – an AIDS activist and visual artist whose performance pieces and memorial works carry immense emotional and historical weight.

- Gilbert Baker – not only an artist, but the designer of the rainbow flag itself, one of the most enduring symbols of queer pride.

Pride as Resistance and Renewal

From murals to fashion, fine art to graffiti, queer art since 1970 has told the story of a people who refused to be erased. Pride in art has been about more than beauty—it has been about survival, protest, celebration, and memory.

As Pride Month continues, remember that the movement is not only political—it is also creative. And in every painting, photograph, poem, and performance, LGBTQ+ artists have asked the world to see them not just as survivors—but as visionaries.