The Fateful Day

By Fremont “Cap” Sawade

‘Twas the day before that fateful day,

December Sixth I think they say.

When leave trucks passed Pearl Harbor clear

The service men perched in the rear.

No thought gave they, of things to come.

For them, that day, all work was done.

In waters quiet of Pearl Harbor Bay,

The ships serene, at anchor lay.

Nor did we give the slightest thought

Of treacherous deeds by the yellow lot.

Those men whose very acts of treason,

Are done with neither rhyme nor reason.

For if we knew what was in store

We ne’re would leave that day before.

For fun and drink to forget the war

Of Britain, Europe, and Singapore.

For all of us there was no fear

This time of peace and Christmas cheer.

Forget the axiom, might is right,

Guardians of Peace, were we that night.

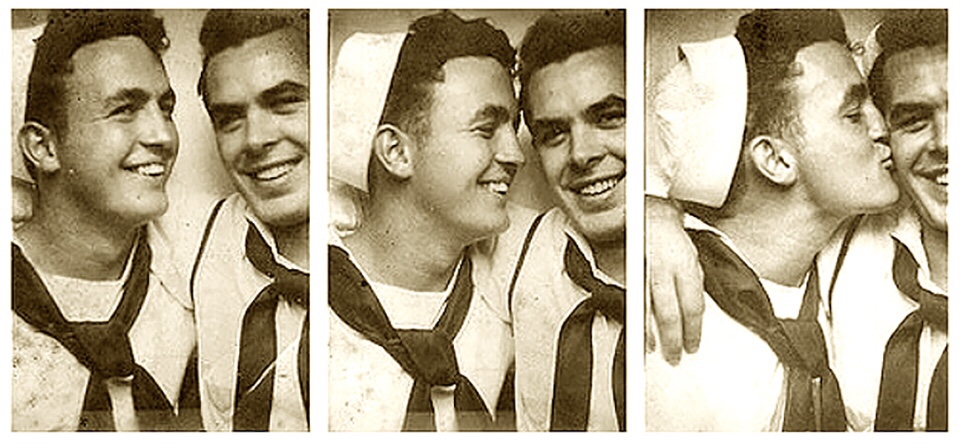

We passed the sailors in cabs galore,

Those men in white who came ashore.

But some will ne’re be seen again,

In care-free fun, those sailor men.

The Sabbath Day dawned bright and clear,

A brand of fire ore the lofty spear,

Of Diamond Head, Hawaii’s own.

A picture itself that can’t be shown,

Unless observed with naked eye,

That makes one look, and stop, and sigh.

What more could lowly humans ask

To start upon their daily task.

The men asleep in barracks late,

Knew no war, that morn at eight.

The planes on fields, their motors cold,

Like sheep asleep among the fold.

The ships at anchor with turbines stilled,

Their crews below in hammocks filled.

And faint, as tho it were a dream,

A sound steels on upon this scene.

A drone of many red tipped things,

The Rising Sun upon their wings.

Those who saw would not believe,

And those that heard could not conceive.

A single shocking, thundering roar,

Followed by another and many more.

To rob the sleep from weary eyes,

Or close forever those that died.

A hot machine gun’s chattering rattle,

Mowed men down like herds of cattle.

A bomb destroys an air plane hangar,

The planes within will fly no more.

Bombs explode upon a ship,

Blasting men into the deep,

To sink without the slightest thought

Of what brought on this hell they caught.

What seems like years, the horrible remains,

Blasting men and ships and planes.

And just as quick as they had come,

Away they went, their foul deeds done.

To leave the burning wreckage here,

The scorching hulks of dead ships there.

And blasted forms of dying men,

Alive in hell, to die again.

At night the skies were all but clear,

The rosy glow of a white hot bier,

Showed on clouds the havoc wrought,

And greedy flames the men still fought.

But from the ruins arose this cry,

That night from those who did not die,

“Beware Japan we’ll take eleven,

For every death of December Seven.”

And from that day there has arisen,

A cry for vengeance, in storms they’re driven.

This fateful day among the ages,

Shall stand out red in Hist’rys pages.

Those men whom homefolk held so dear,

Will be avenged, have no fear.

And if their lives they gave in vain,

Pray, I too, may not remain.

About the Poet and the Poem

Fremont “Cap” Sawade, who passed away at age 94 in 2016, wrote this the poem right after Pearl Harbor. Sawade was assigned to an Army anti-aircraft regiment in Honolulu on liberty, having breakfast the morning of the attack on Pearl Harbor eighty years ago today. Loud explosions sent him racing to his base in a cab. He could see the Japanese planes flying low, dropping bombs, and strafing battleships with machine gun fire. Back at Camp Malakole, Sawade ducked for cover when the Japanese Zeros strafed it. The attack caught the Americans completely off guard. Sawade said his unit didn’t even have ammunition for their big guns.

Two days later, with the wreckage of the Pacific Fleet still smoking, he sat at a desk at Hickam Field and started writing a poem. He’d never written one before. He hasn’t written one since. But over the next week, this one flowed out of him. He called it “The Fateful Day.” It captures how idyllic life was, before the attack. How lucky the service members felt to wake up every day with a view of Diamond Head. The poem captures their surprise, and then their anger at the Japanese, including a slur that was common then, offensive now. It captures the horror — “A hot machine gun’s chattering rattle/Mowed men down like herds of cattle” — and the raw thirst for vengeance.

He came home from the war to his native San Diego, worked a variety of jobs, including 10 years as a building inspector for the city of El Cajon. He got married, raised a family, and lived in Rancho Bernardo with his wife, Gloria. Over the years, he showed the poem to a few friends. He shared it a time or two in military newsletters. But the truth is he never thought it was anything special. However, today, nearly 80 years after he wrote it, it serves as a primary source for the thoughts of the men who lived through the attack on Pearl Harbor that fateful Sunday morning.