Palm Springs

By Christian Gullette

We drink Fernet by ironic sculptures

under misters that make our bangs damp.

It’s our anniversary,

though that time feels faint.

We are searching for a place

to escape his diagnosis,

laws against gay marriage,

our leaky, flat roof.

Every Memorial Day

and Labor Day, we go to the desert.

Sometimes also the Fourth

of July.

Palm Springs rewinds things.

We almost buy that mid-century chair

proud of our rule that love for it

needs to be immediate.

At the Parker, a guy with a calf tattoo

brings drinks.

You can ask for anything here.

We toast to another year without cancer.

After dinner, we wander the hotel hedge maze,

nowhere to go that late but home.

About the Poem

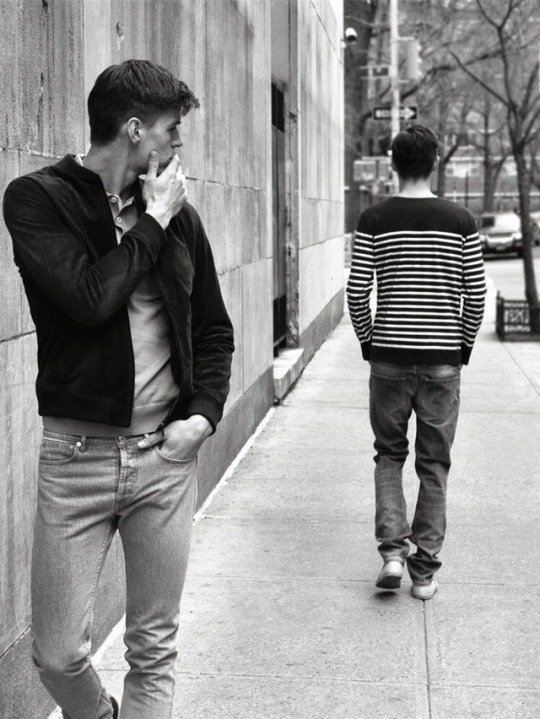

Christian Gullette’s Palm Springs is a poem of sleek surfaces and simmering tensions. The desert resort town—so often painted in mid-century glamour—becomes here a backdrop for longing, performance, and queer recognition. Palm Springs is both mirage and mirror: a place where artifice and authenticity blur, where the hot light reveals as much as it conceals.

The poem doesn’t settle for nostalgia or kitsch. Instead, it examines what it means to inhabit a space so layered with history, expectation, and desire. Gullette’s Palm Springs isn’t just a sunny escape; it’s a charged landscape where intimacy pulses against the façade of cocktails, poolsides, and desert views.

Queer poets have long re-imagined spaces marked by leisure or luxury as sites of deeper reflection, and Gullette does just that. Palm Springs is lush but not naïve, glamorous but not shallow. It suggests that behind every stylish lounge chair or glimmering pool, there’s a body hoping to be seen, a self negotiating the terms of love and exposure.

As readers, we are left with a sense of recognition—of what it means to find ourselves in a place where beauty and fragility intertwine, where queer desire is both illuminated and complicated by the desert sun.

About the Poet

Christian Gullette is an acclaimed poet and translator based in San Francisco. His debut collection, Coachella Elegy (Trio House Press, 2024), earned critical praise and became a finalist for the 2025 Northern California Book Award in Poetry. The volume has also been featured on several “must‑read” lists from LitHub, Electric Lit, Alta Journal, and Debutiful. Ron Charles of The Washington Post Book Club lauded its “cool, elegantly controlled poems,” while Publishers Weekly described it as “tender and deliciously sly.”

Gullette holds a Ph.D. in Scandinavian Languages and Literatures from the University of California, Berkeley, where he explored themes of sexuality, race, and neoliberalism in Swedish literature and film. He also earned an MFA from the Warren Wilson MFA Program for Writers and an M.Ed. from George Washington University, following a B.A. in English from Bates College. As a translator, he works professionally with Swedish texts—including poetry by Kristofer Folkhammar and Jonas Modig, as well as cookbooks by Roy Fares, Lisa Lemke, and others.

He currently serves as editor-in-chief of The Cortland Review and has taught workshops for the Kenyon Review Online Writers Workshops and the Poetry Society of New York. He was awarded a Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference scholarship in 2022.

A longtime resident of San Francisco, Gullette lives with his husband, Michael. His work intricately interweaves personal grief—including living through his husband’s ocular cancer diagnosis and the loss of his brother—with the luminous terrain of California’s desert landscapes, exploring themes of desire, mortality, visibility, and renewal.