The Love of Narcissus

By Alice Meynell

Like him who met his own eyes in the river,

The poet trembles at his own long gaze

That meets him through the changing nights and days

From out great Nature; all her waters quiver

With his fair image facing him for ever;

The music that he listens to betrays

His own heart to his ears; by trackless ways

His wild thoughts tend to him in long endeavour.

His dreams are far among the silent hills;

His vague voice calls him from the darkened plain

With winds at night; strange recognition thrills

His lonely heart with piercing love and pain;

He knows his sweet mirth in the mountain rills,

His weary tears that touch him with the rain.

About the Poem

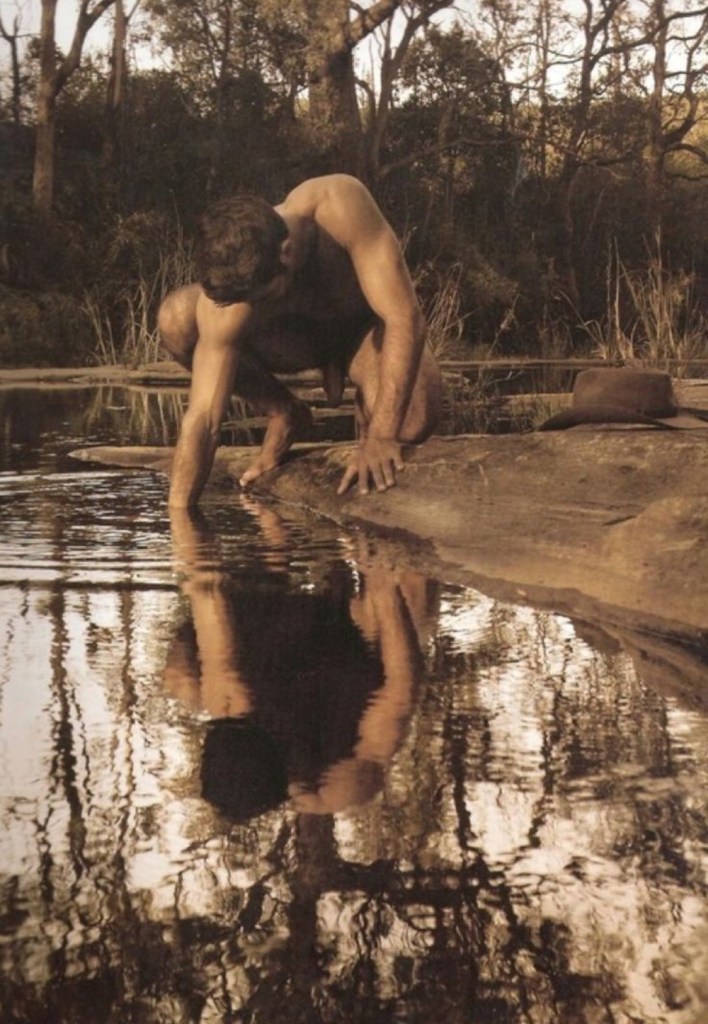

If you are not familiar with the Greek myth about Narcissus, he was born in Thespiae in Boeotia, the son of Cephissus (the personification of the Boeotian river of the same name) and the nymph Liriope. His mother was warned one day by the seer Teiresias that her son would live a long life as long as “he never knows himself.” Narcissus was known for his incredible beauty, and as he reached his teenage years, the handsome youth never found anyone that could pull his heartstrings. He left in his wake a long trail of distressed and broken-hearted maidens and even spurned the affections of one or two young men. Then, one day, he chanced to see his own reflection in a pool of water and, thus, discovered the ultimate in unrequited love: he fell in love with himself. Naturally, this one-way relationship went nowhere, and Narcissus, unable to draw himself away from the pool, pined away in despair until he finally died of thirst and starvation. Immortality, at least of a kind, was assured, though, when his corpse (or in some versions the blood from his self-inflicted stab wound) turned into the flowers which, thereafter, bore his name.

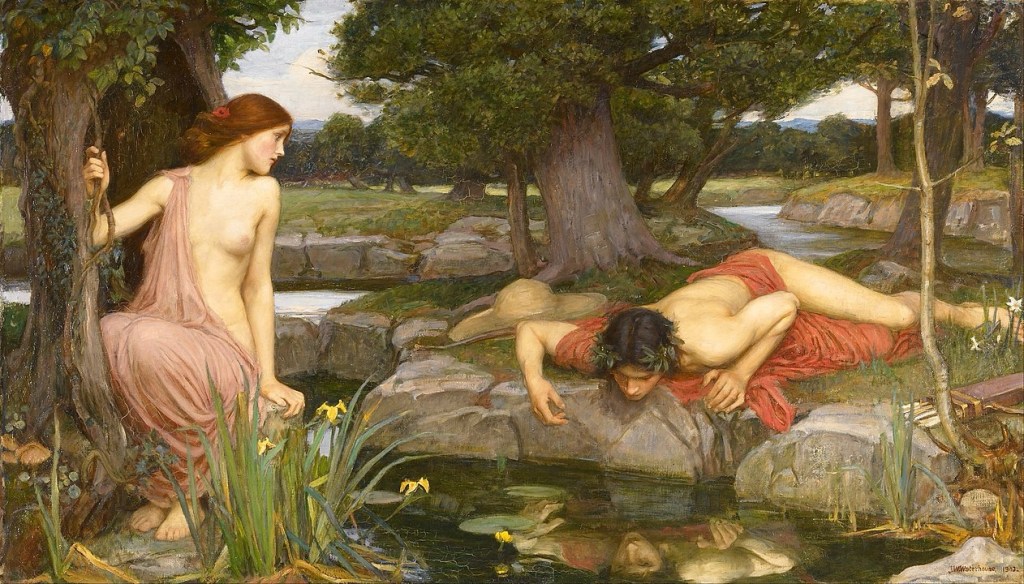

Echo and Narcissus by John William Waterhouse (1903 oil painting)

Narcissus appears in other myths as well, especially the myths surrounding mountain nymph Echo. Another version of the myth appears in the work of the Roman writer Ovid. In this telling, Narcissus is as handsome as ever but cruelly refuses the advances of Echo. The lovely nymph, heartbroken, wastes away and dies with only her voice remaining to echo her plight. As a punishment for his neglect, Narcissus is then killed. Another version has Echo punished by Hera because she kept the goddess distracted with stories while the lovers of her husband Zeus, the mountain nymphs, escaped Mt. Olympus without notice. This explains why Echo could only repeat what others said to her. It is Echo in this form that Narcissus comes across one day while hunting deer in the forest. After a useless exchange of repeated words and statements, Echo tries to embrace the youth, but he rejects her and dashes off back home. Echo then pines away in the forest so that her body eventually perishes and only her voice remains.

Echo (right) with Narcissus, from a fresco in Pompeii

Unlike for Greek artists, the Roman version of Narcissus and Echo was a very popular subject in Roman art and is seen in almost 50 wall paintings at Pompeii alone. Renaissance art also took a shine to Narcissus; the story involving light, and reflection proved irresistible to Caravaggio, who captured the myth in his celebrated 16th-century CE oil painting. Finally, his name lives on today in psychoanalysis where narcissism refers to the personality disorder of excessive self-admiration and preoccupation with one’s appearance.

In the poem above, Meynell describes a poet as being similar to Narcissus looking back on himself through his poetry as a form of vanity. In this way, similar to Narcissus who lives on as the flower, the poet lives on forever through his poetry.

About the Poet

Alice Christiana Gertrude Meynell was born on October 11, 1847, in Barnes, west London, to Thomas Thompson, a lover of literature and friend of Charles Dickens, and Christiana Weller, a noted painter and concert pianist. Thompson insisted on a classical education for his children, who were homeschooled. This education, as well as the verses of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Christina Rossetti, inspired Meynell to try writing poetry as a teen.

Her poetry is characterized by its formal precision and intellectual rigor. She often explores themes of faith, nature, and the human condition with a restrained and understated elegance. Her focus on the musicality of language and concise imagery makes her work continue to be studied and enjoyed today.

Meynell suffered from poor health throughout her childhood and adolescence. In 1868, while she was recuperating from one of these bouts of illness, she converted to Roman Catholicism. It was also during this time that she fell in love with Father Augustus Dignam, a young Jesuit who had helped with her conversion and received her into the church. Dignam inspired some of her early love poems, including “After a Parting” and the popular “Renouncement.” Meynell and Dignam continued to correspond for two years until they fell out of touch.

She was influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite poets, an artistic movement founded in 1848 by the poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the painters John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt, who is often credited with the group’s name, which indicates not a dismissal of the Italian painter Raphael, but rejection of strict aesthetic adherence to the principles of composition and light characteristic of his style. The Pre-Raphaelites’ commitment to sincerity, simplicity, and moral seriousness is evident in the contemplative but uncomplicated subjects of its poetry and in the religious, mythical, and literary subjects depicted in its paintings. Meynell shared their interest in symbolism and aesthetic beauty, but her poetry also displays a strong intellectual and spiritual depth influenced by her Catholic faith. Meynell’s work was admired by contemporaries such as George Meredith, Coventry Patmore, and John Ruskin, and she played a significant role in shaping the literary landscape of her time.

In 1875, Meynell published her first poetry collection, Preludes (Henry S. King & Co.), which was received with great success. English poet and novelist Walter de la Mare called her one of the few poets “who actually think in verse.” Two years later she married Wilfred Meynell, another Catholic convert who was working as a journalist for a number of Catholic periodicals in London. He soon became the successful editor of the monthly magazine Merry England. Alice Meynell joined her husband at Merry England as coeditor, helping to keep the magazine at the helm of the Catholic literary revival. Her writing won her the recognition of other members of the literary elite of the time, such as Coventry Patmore, Francis Thompson, Oscar Wilde, and W. B. Yeats.

Meynell balanced her time between her journalism work with Merry England, her social life among the literati, her home life (she mothered eight children, one of whom died as an infant), and her social activism. She worked to improve slum conditions and prevent cruelty to animals, but she was best known for her work for women’s rights. Meynell worked with the Women’s Suffrage Movement and fought for workers’ rights for women. During this busy period, Meynell did not write much poetry; her second book, Poems (Elkin Matthews & John Lane, 1893), was published nearly two decades after the release of her debut. She published several more poetry collections in her lifetime: Ten Poems (Romney Street Press, 1915); Collected Poems of Alice Meynell (Burns and Oates, 1913); Later Poems (John Lane, 1901); and Other Poems, which was self-published in 1896. Restrained, subtle, and conventional in form, Meynell’s poems are reflections on religious spirit and belief, love, nature, and war.

She was twice considered for the post of Poet Laureate of England—upon the deaths of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, in 1892 and Alfred Austin in 1913. Elizabeth Barrett Browning is the only other woman who had been considered for the post up to that point. Meynell continued writing until her death. After a series of illnesses, she died on November 27, 1922. A final collection, Last Poems (Burns and Oates), was published posthumously a year later.

August 27th, 2024 at 9:32 am

I enjoyed reading about Narcissus. And the photo of the young man shows something hanging down which I enjoy too.

August 27th, 2024 at 3:08 pm

I’m a huge fan of the Pre-Raphaelite movement—whether poetry or painting. I wasn’t able to get to the Tate Britain on my last trip to London, but they have an outstanding collection of Pre-Raphaelite pictures