Monthly Archives: May 2025

Birthright Citizenship

Disclaimer: this is not my usual type of post, but as a historian, it is something I feel very passionate about. I hate when people try to rewrite history to suit their own political agenda. Republicans do it constantly, and it is a typical fascist ploy to gain support from the ignorant. (As I have always said, ignorance isn’t stupidity, though they can go hand in hand, ignorance is the disdain for learning.

In recent years, attempts have been made—most prominently by Trump and his allies—to narrow the scope of the 14th Amendment’s Citizenship Clause by asserting that it was intended only to apply to formerly enslaved people after the Civil War. This interpretation, if adopted, would dramatically alter the constitutional guarantee of birthright citizenship by excluding the U.S.-born children of undocumented immigrants or non-citizen parents. On January 20, 2025, Trump signed Executive Order 14160, titled “Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship,” aiming to end birthright citizenship for children born in the United States to non-citizen parents, including undocumented immigrants and those on temporary visas. The executive order asserts that the 14th Amendment’s Citizenship Clause does not apply to these children, challenging longstanding interpretations of the Constitution.

Trump’s reinterpretation of the 14th Amendment is not only legally unsound, but it also contradicts the very principles of originalism—a judicial philosophy espoused by several current members of the United States Supreme Court, including Justices Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, Amy Coney Barrett, and Brett Kavanaugh. Originalism holds that the Constitution should be interpreted according to its original public meaning at the time of its ratification. An honest application of this methodology to the 14th Amendment—adopted in 1868—reveals that the framers and ratifiers understood birthright citizenship to extend far beyond the formerly enslaved. The original debates, statutory context, and legislative intent make clear that the amendment was designed to establish a broad and enduring principle of jus soli (citizenship by place of birth), not a narrow race- or status-specific remedy.

The first sentence of the 14th Amendment reads:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

This language, while triggered by the injustices of slavery and the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision (1857), was not restricted to formerly enslaved persons. Rather, it established a general rule of national citizenship. As Senator Jacob Howard (1805-1871), who introduced the Citizenship Clause in the Senate, explained during the 1866 debates, it would “include every class of persons” born in the United States, with only narrow exceptions—notably, the children of foreign diplomats and tribal members under, sovereign jurisdiction.

Representative John Bingham (1815-1900), the principal framer of Section 1, likewise affirmed that the amendment was meant to secure the rights of “every human being born within the jurisdiction of the United States of parents not owing allegiance to any foreign sovereignty.” This phrasing did not exclude immigrants; rather, it excluded only those legally insulated from U.S. law, such as ambassadors and ministers. Immigrants, whether legally or illegally present, are subject to U.S. jurisdiction in every meaningful legal sense.

Thus, under originalist principles, the public understanding of the 14th Amendment in 1868 included birthright citizenship for all those born on American soil and subject to its laws, regardless of their parents’ status.

The broader context of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, passed shortly before the 14th Amendment, further undermines any restrictive reading. That law declared:

“All persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power… are hereby declared to be citizens.”

This clause formed the legislative basis for the 14th Amendment and demonstrates that Congress deliberately created a universal standard, not one limited to the formerly enslaved. While the Amendment’s ratification followed the Civil War and was motivated in part by the need to secure citizenship for freedmen, its framers understood that equal citizenship was a universal principle, not a racially contingent one.

This understanding has been upheld repeatedly by the Supreme Court, most notably in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898), which affirmed that a child born in the United States to Chinese parents—who were not U.S. citizens and were barred from naturalization—was nonetheless a U.S. citizen under the 14th Amendment. That decision relied heavily on both the text and historical intent of the Amendment, and it is directly contrary to the Trump-era argument that children of non-citizens are not constitutionally entitled to citizenship.

For originalists, the legitimacy of constitutional interpretation rests on fidelity to the Founders’ and ratifiers’ understanding. The attempt to redefine the 14th Amendment’s reach based on a selective, ahistorical reading that imagines it applied only to freed slaves is inconsistent with the actual record. It distorts the original public meaning by conflating historical motivation with constitutional scope. The motivation for an amendment may be rooted in a particular crisis—like the abolition of slavery—but its language and application must be understood in light of the general principles it enshrines.

Moreover, originalism demands that courts avoid imposing modern policy preferences or political pressures onto the Constitution. The Trump administration’s push to reinterpret the Citizenship Clause is a modern political maneuver, not a historically grounded legal argument. To accept such a revisionist reading would be to violate the very core of originalist jurisprudence. The legality of Executive Order 14160 is currently under review by the U.S. Supreme Court in the consolidated case Trump v. CASA. The framers of the amendment wrote in broad, inclusive terms—and debated and defended those terms publicly. They did not write a clause about race or lineage; they wrote one about the universal promise of citizenship to anyone born on American soil and subject to its laws.

Originalists on the Supreme Court, therefore, have a duty to honor that promise—not just as a matter of precedent or policy, but as a matter of fidelity to the constitutional text and its original meaning. Therefore, from an originalist perspective, the executive order contradicts the original understanding and judicial interpretation of the 14th Amendment. Originalist justices should uphold the Constitution’s text and historical intent by rejecting the executive order’s attempt to redefine birthright citizenship. And, while Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, and Ketanji Brown Jackson do not identify as originalists, they would likely rule against Trump for the reinterpretation of a long standing understanding of the 14thAmendment. That leaves only Justice Alito, who occasionally employing originalist arguments, so whatever side of the fence he falls on this issue. Trump v. CASA will ultimately come down to the judicial consistency and moral integrity of their originalist ideology, though we know the most conservative Supreme Court justices, particularly Thomas and Alito, have no moral integrity or judicial consistency and are inherently political in their rulings.

All of that being said, after yesterday’s hearings, it should be a unanimous summary judgement in favor of CASA. Sadly, I have little faith that this will be the case, especially with the current politicized nature of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Weekend Ahead

I’m hoping this afternoon will be the beginning of a long weekend. I emailed my boss, who has been on vacation for the last week about taking some of my remaining vacation days. I had asked to take today off, but I did not realize it was a travel day for her. I think she was coming back from a conference in England, but since she doesn’t communicate things like that to us, I’m not completely sure where she had been. Anyway, when I found out she was traveling, I assumed I would not hear back from her. I could have texted her, but I would not have wanted to be bothered on a day when I had been traveling all day. So, when she gets back to work today, I will talk to her about taking this afternoon off. I have a half day that I need to take anyway. I’m already scheduled to be off tomorrow, and I’m going to see about taking Monday off as well. Anyway, we’ll see how that works out.

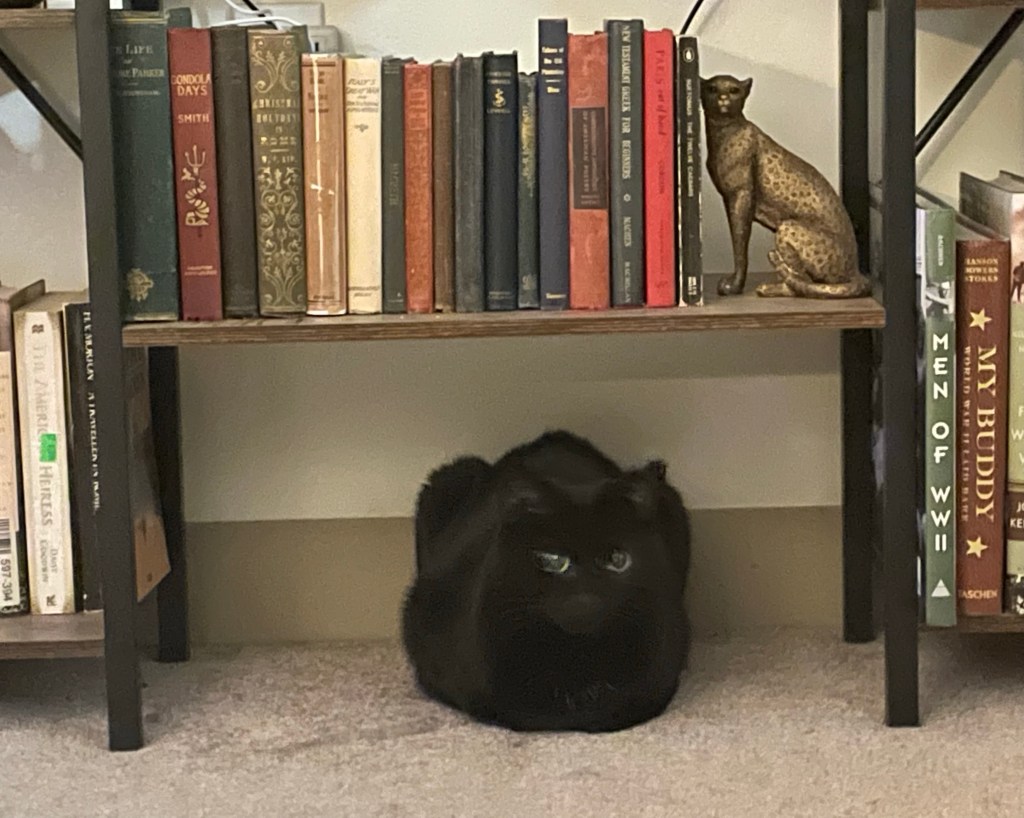

If I do take this time off, I’m hoping I can relax and read. We have several rainy days ahead, and I have always loved curling up with a book on a rainy day. I really didn’t have much to say today, but I will post my Isabella pic of the week. I think I have posted this picture before, but it’s one of my favorites:

Khajuraho Temples

The temples of Khajuraho, a UNESCO World Heritage site located in Madhya Pradesh, India, are renowned for their intricate sculptures that celebrate the full spectrum of human life—spiritual, sensual, and mundane. Constructed between the 10th and 12th centuries CE under the rule of the Chandela dynasty, these temples have drawn global attention for their uninhibited erotic carvings. While most focus has traditionally been directed toward heterosexual imagery, the presence of male same-sex activity in the sculptural program offers a rare and illuminating glimpse into a pre-modern Indian worldview that acknowledged, depicted, and integrated diverse expressions of desire, including male-male eroticism, without censure.

Among the 85 temples originally built at Khajuraho, 22 remain today. Temples like the Kandariya Mahadeva, Lakshmana, and Vishvanatha house the majority of the erotic sculptures. These carvings are typically located on the outer walls and are interspersed among depictions of deities, mythical creatures, daily life, and celestial beings. In this context, the erotic is not marginal or profane—it is part of a holistic worldview that includes kama (desire) as one of the four essential goals of life, alongside dharma (duty), artha (prosperity), and moksha (liberation).

Within this framework, scenes of male same-sex activity appear—never as the dominant theme, but as a recognized and unashamed element of human and divine experience. One well-documented relief on the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple portrays three male figures: two engaged in what appears to be anal intercourse while the third supports or observes. The composition, carved with anatomical clarity and sensual expressiveness, is neither hidden nor diminutive. Instead, it is seamlessly integrated with other sexual depictions, suggesting that such interactions were not viewed as abnormal or unworthy of representation.

The Khajuraho sculptures are informed by Tantric philosophy, which celebrates the union of opposites—male and female, mortal and divine, physical and spiritual. Tantra does not moralize sexual behavior but instead sees it as a path to transcendence when practiced with awareness and ritual purpose. In such a framework, the body is not a source of shame but a vehicle for experiencing and accessing the sacred. This philosophical backdrop helps explain the inclusion of non-normative sexualities in the temple art.

Moreover, the historical Indian worldview, as evidenced in ancient texts like the Kama Sutra and the Natyashastra, acknowledged and codified categories for male-male desire. The Kama Sutra describes the behavior of the kliba—a term that included a variety of gender-nonconforming or homosexual individuals—and elaborates on oral sex between men without moral condemnation. The presence of male same-sex depictions at Khajuraho may be seen as a visual extension of these texts, reflecting their acceptance within elite court and religious circles.

The British colonial period marked a turning point in the interpretation of Indian art and sexuality. Victorian sensibilities, combined with Christian morality, led to a widespread suppression of India’s diverse sexual past. Erotic art was dismissed as “obscene” or “degenerate,” and the Khajuraho sculptures were either censored or misinterpreted. The presence of male same-sex acts, in particular, was downplayed or ignored in early archaeological reports, a silence that endured into much of the 20th century.

Only in recent decades have Indian and international scholars begun to reassess Khajuraho through lenses unclouded by colonial morality. Researchers such as Devdutt Pattanaik and Ruth Vanita have foregrounded these representations as evidence of a more fluid and inclusive premodern Indian culture. In doing so, they challenge modern narratives that frame homosexuality as a “Western import” or a postcolonial phenomenon.

The male same-sex depictions at the Khajuraho Temples serve as powerful reminders of a historical moment when erotic plurality was not stigmatized but sculpted in stone for the divine and the earthly to witness. These carvings do not merely reflect acts of physical pleasure—they symbolize a cultural acceptance of the full range of human desire. As India and the world continue to grapple with questions of sexual identity and historical memory, the Khajuraho temples stand as enduring monuments to a time when the sacred and the sensual, including love between men, coexisted without shame.In recognizing and reclaiming these images, we honor a forgotten legacy—one that whispers across time from temple walls that have seen centuries, reminding us that queerness is not an aberration in Indian history, but a thread woven into its very cultural fabric.

If I Could Tell You

If I Could Tell You

By W H Auden

Time will say nothing but I told you so,

Time only knows the price we have to pay;

If I could tell you I would let you know.

If we should weep when clowns put on their show,

If we should stumble when musicians play,

Time will say nothing but I told you so.

There are no fortunes to be told, although,

Because I love you more than I can say,

If I could tell you I would let you know.

The winds must come from somewhere when they blow,

There must be reasons why the leaves decay;

Time will say nothing but I told you so.

Perhaps the roses really want to grow,

The vision seriously intends to stay;

If I could tell you I would let you know.

Suppose all the lions get up and go,

And all the brooks and soldiers run away;

Will Time say nothing but I told you so?

If I could tell you I would let you know.

About this Poem

W. H. Auden’s “If I Could Tell You” is one of the most elegant and haunting examples of the villanelle* form in 20th-century poetry. Written in 1940, during a time of global uncertainty and personal introspection, the poem reflects Auden’s preoccupations with fate, time, and the limits of human understanding. Through the disciplined repetition inherent to the villanelle structure, Auden explores the futility of attempting to predict or control the future, as well as the painful inability to articulate certain emotional truths. The poem is widely celebrated not only for its formal mastery but also for the quiet emotional resonance it achieves within the constraints of a tightly ordered verse.

The speaker begins with the striking line, “Time will say nothing but I told you so,” immediately positioning time as a silent but omniscient force. This refrain recurs throughout the poem, becoming a kind of mantra that expresses the speaker’s sense of resignation. Time, in Auden’s conception, offers no guidance or foresight; it speaks only after events have unfolded and merely to affirm what could not be known beforehand. The second refrain—“If I could tell you, I would let you know”—is equally suggestive. It conveys a deep desire to communicate something essential, perhaps a truth about love, destiny, or mortality, yet the speaker admits that such knowledge lies beyond the reach of speech. This interplay between knowing and unknowing, between expression and silence, gives the poem its emotional power.

Throughout the poem’s six stanzas, Auden employs the villanelle form to echo the very limitations he describes. The repetition of the refrains mirrors the cyclical nature of thought, especially when grappling with uncertainties about the future or love. Each repetition slightly alters in context, accumulating new emotional weight as the poem progresses. This structural device reinforces the central themes: human beings return again and again to the same questions about time, fate, and communication, but definitive answers remain elusive. The fixed form, with its repeated lines and rhyme scheme, becomes a metaphor for the limits of human perspective—we can frame questions and revisit them, but we may never escape their orbit.

Despite its philosophical tone, the poem also carries a deeply personal undercurrent. There is an implicit intimacy in the speaker’s voice, a sense that this is a private confession addressed to someone the speaker longs to reach. Lines such as “Suppose the lions all get up and go, / And all the brooks and soldiers run away” evoke surreal imagery that suggests a world in flux, where nothing can be counted on to stay or behave as expected. The poem ultimately resists clarity or conclusion; instead, it invites readers to dwell in uncertainty. This refusal to offer easy resolution is part of what makes the poem so enduring—it captures a universal human condition with spare, deliberate language.

“If I Could Tell You” is also a classic example of the villanelle because of how skillfully Auden uses the form to enhance, rather than restrict, meaning. The villanelle’s strict pattern of nineteen lines—five tercets and a final quatrain, with two alternating refrains—often leads poets toward predictability or formal stiffness. Auden, however, embraces these limitations to serve the poem’s meditation on fate. The refrains are not static repetitions but dynamic reframings, deepening with each recurrence. The rhyme scheme (ABA throughout, with the final stanza ABAA) provides musicality without drawing undue attention to itself. This seamless integration of structure and sentiment is what makes Auden’s villanelle exemplary.

In conclusion, “If I Could Tell You” is a masterwork of poetic form and philosophical inquiry. It demonstrates how the villanelle, often associated with obsessive or lyrical themes, can also express complex reflections on time, knowledge, and emotional truth. Auden’s use of the form allows for a careful layering of meaning, where each return to the refrain evokes not repetition, but revelation. The poem lingers in the reader’s mind long after the final lines, not because it offers answers, but because it gives voice to the yearning for them. Through its elegant structure and aching restraint, “If I Could Tell You” stands as one of the most affecting and enduring villanelles in English literature.

* Villanelles and sonnets are my two favorite poetic forms. The rigidity of the rules of these forms takes a truly dedicated person to write. I love the repetition in a villanelle, and sonnets always have that little twist at the end. In case you are not familiar with the rigid structure of these poems:

A villanelle is a 19-line poem composed of five tercets followed by a quatrain, with two repeating refrains and a strict ABA rhyme scheme. The first and third lines of the opening stanza alternate as the final lines of the subsequent stanzas and both reappear in the concluding quatrain. This repetitive structure creates a lyrical, cyclical effect often used to express obsession, longing, or inevitability.

A sonnet is a 14-line poem written in iambic pentameter with a specific rhyme scheme and structure. The two most common types are the Petrarchan (Italian) sonnet, which divides into an octave and a sestet (usually ABBAABBA CDECDE), and the Shakespearean (English) sonnet, which has three quatrains and a final couplet (ABAB CDCD EFEF GG). Sonnets traditionally explore themes like love, time, beauty, and mortality.

About the Poet

W. H. Auden (Wystan Hugh Auden) was born on February 21, 1907, in York, England, and raised in an intellectually vibrant household in Birmingham. He studied English literature at Christ Church, Oxford, where he emerged as a brilliant and unconventional young poet. In the 1930s, Auden became a central figure in British literary and political life, known for his formal innovation, sharp intellect, and engagement with social and psychological themes. His early poetry often reflected a concern with war, oppression, and spiritual crisis, influenced by his travels in Germany and Spain during periods of political upheaval.

Auden was gay, and while he never publicly identified as such in a modern political sense—given the cultural and legal constraints of his time—his sexuality was a formative aspect of his identity and creative life. Though often discreet in public, he was relatively open within his artistic circles and close relationships. His lifelong partnership with the American poet Chester Kallman, beginning in 1939, deeply shaped both his personal life and literary output, even as their romantic relationship eventually evolved into a complicated, platonic companionship. Many of Auden’s poems, particularly his love lyrics, carry a tone of longing, vulnerability, and emotional depth that reflect his experiences as a gay man seeking intimacy in a world that often denied him open recognition.

Auden emigrated to the United States in 1939 and became a U.S. citizen in 1946. This move marked a shift in both geography and poetic style: his later work became more philosophical, often concerned with theology, morality, and the inner life. Still, the emotional resonance of his early relationships and romantic disappointments lingered in his poetry. Works like “Lullaby,” “Funeral Blues,” and “The Sea and the Mirror” delicately explore themes of homoerotic desire, loss, and spiritual reconciliation, even when not explicitly naming the gender of the beloved. Auden’s ability to navigate such personal material through layered language and formal control allowed him to speak of love and pain in ways that transcended the boundaries of his era.

He spent his final years between New York and Austria, continuing to write, lecture, and influence generations of poets. W. H. Auden died on September 29, 1973, in Vienna. Today, he is remembered not only as one of the most technically gifted and intellectually adventurous poets of the 20th century but also as a pioneering voice in the canon of LGBTQ+ literature. His work stands as a testament to the quiet, resilient dignity with which he lived his life and articulated a deeply personal vision of love, loneliness, and human connection.

Not Hating This Monday Morning

Monday mornings usually have a reputation, and let’s be honest—they’ve earned it. The alarm goes off too early, my morning cup of tea never seems strong enough, and I’m just not feeling any motivation. But this Monday? This Monday, I’m not hating at all.

For once, I don’t have to go into work today. I had to switch my off day from Wednesday to Monday this week because I’ve got an event at the museum in the middle of the week. So today, while most of the world is fighting off the Monday blues and rushing off to jobs, meetings, and traffic jams, I’m enjoying the rare pleasure of a quiet morning, guilt-free.

I slept in a bit—not too late, just enough to feel indulgent, but late enough to piss off Isabella. The weather outside is behaving, it’s supposed to be a beautiful sunny day with a high of 71 degrees. My tea tastes like it actually wants to be helpful, and I’ve got absolutely nothing on my to-do list until my appointment with my trainer at 3 pm. That’s right, I’ll be spending my afternoon getting stronger, one rep at a time (with a little side motivation—Neo is easy on the eyes).

There’s something surprisingly luxurious about having a day off when the rest of the world doesn’t. It feels like I’ve been let in on a secret, or like I’m skipping school with permission. It’s not a vacation exactly—but it is a breath. And maybe that’s what I needed more than anything today: a pause, a stretch, a reset.So, for now, I’m going to enjoy this Monday for the anomaly it is—quiet, slow, and entirely mine. I hope wherever you are, you can find a little space for that too.