Some of you may know that my original academic passion—and the reason I first went to graduate school—was to study military history, with a particular focus on the First World War. Ever since I took my first undergraduate course on WWI, I’ve been captivated by the conflict: the way it reshaped nations, upended empires, and left cultural and emotional reverberations we still feel more than a century later. I’ve long been drawn to the poetry of the war, as well as the deeply human stories of the individuals and communities who lived through it.

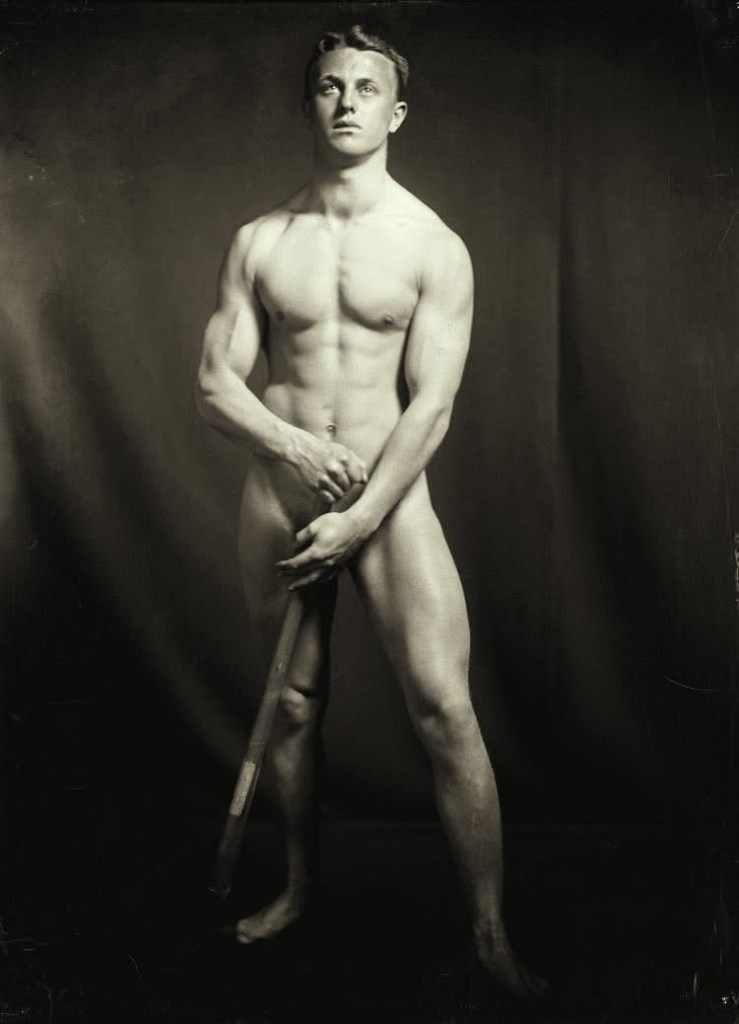

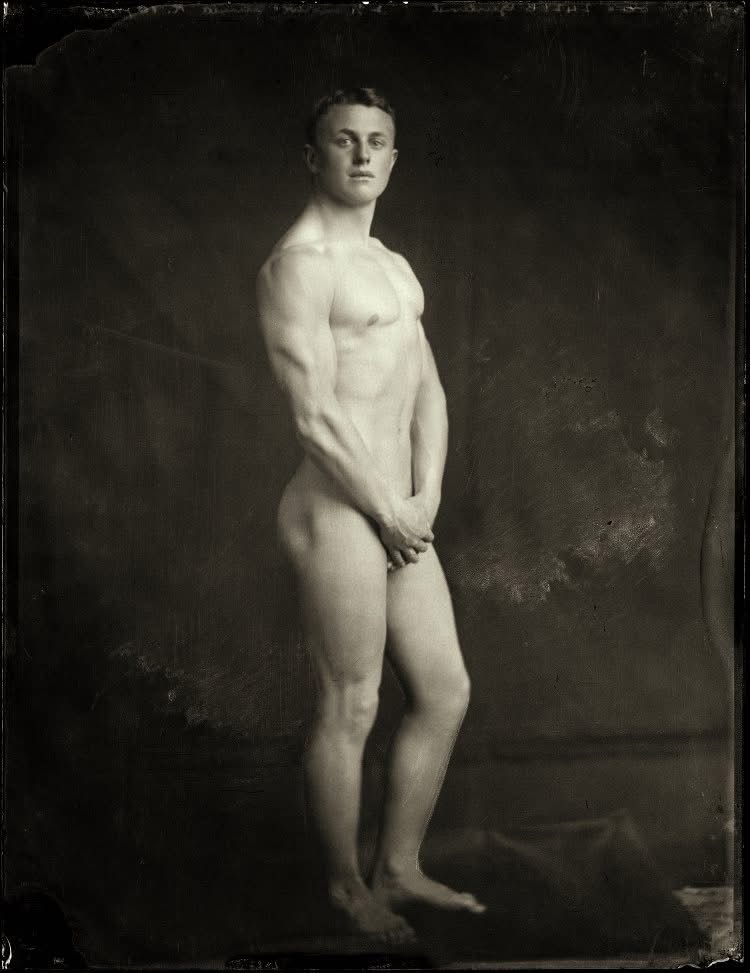

That’s why, when I came across a set of nude photographs taken of New Zealand soldier Lieutenant Edgar Henry Garland, I was immediately intrigued. The images are striking—not just for their artistic composition, but for the questions they raise about masculinity, memory, and identity during wartime. This week’s art history post centers on three rare and intimate photographs of a single soldier. There may have been others like them, but this particular case remains one of the most compelling and well-known examples of its kind.

Uncovering the Man Behind the Uniform: Art, Intimacy, and Queer Visibility in a WWI Portrait

In the archives of New Zealand’s photographic history lies a haunting and striking series of images: nude portraits of Lieutenant Edgar Henry Garland, a World War I soldier, posed with classical grace and remarkable vulnerability. Captured by the studio of S. P. Andrew Ltd., these images raise fascinating questions about art, masculinity, and queer subtext in the early 20th century.

At first glance, Garland might seem like any young officer from the Great War—handsome, lithe, a product of Edwardian values and imperial loyalty. But his story is far more remarkable.

Born in 1895, Edgar Henry Garland served with distinction in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force during World War I. He fought on the Western Front and was captured by German forces, becoming a prisoner of war. What set Garland apart was not just his courage in combat, but his extraordinary persistence in trying to escape captivity. He attempted to escape seven times from various POW camps—an astonishing feat that earned him admiration both during and after the war. His repeated escapes were acts of daring and defiance that turned him into a kind of folk hero in New Zealand military lore. By war’s end, he was among the most celebrated escapees in New Zealand’s wartime record.

And yet, tucked away behind this legacy of bravery is a quieter, more intimate chapter—one not written in medals or official commendations, but in a series of photographs that strip away the uniform and expose the man beneath.

These nude images were taken by S. P. Andrew Ltd., one of the most respected portrait studios in New Zealand. Founded by Samuel Paul Andrew, the Wellington-based studio was renowned for its official portraits of governors-general, judges, and prime ministers. It specialized in formal, large-format images meant to convey dignity, authority, and professionalism. That such a prestigious studio would also produce a set of male nudes—posed with artistry and elegance—speaks volumes about the complexity of photographic culture at the time.

So why were these photographs taken?

At one level, they reflect the influence of classical artistic ideals. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the nude male form was seen—at least within certain artistic circles—as a symbol of strength, youth, and aesthetic perfection. Garland’s poses recall ancient Greek statuary, suggesting a deliberate invocation of heroism and beauty. For a young man who had survived war and captivity, these images may have served as a personal monument—an assertion of vitality, resilience, and self-possession.

But there are other possibilities too.

The photographs may have been taken as private keepsakes, either for Garland himself or for someone close to him. Garland never married, and little is known about his private relationships. The possibility that these images were intended for a romantic or intimate partner—perhaps even a male lover—has been raised by queer historians who see in the photographs a coded form of homoerotic expression. The tenderness of the poses, the elegance of the lighting, and the sheer vulnerability on display all hint at a relationship between photographer and subject that goes beyond documentation.

Indeed, these photographs function within a long tradition of discreet queer representation. In an era when homosexuality was criminalized and forbidden by military and civil law, photography could serve as a silent language of desire. Studios like S. P. Andrew—though publicly respectable—may have discreetly permitted or even participated in the creation of such images for trusted clients. This wasn’t pornography; it was art. But it was art with layers of subtext—subtext that speaks volumes to those willing to see it.

Whether these photographs were meant as aesthetic studies, personal mementos, or secret love letters, they offer a rare and poignant glimpse into the inner life of a man whose public legacy is defined by heroism. In these images, we see not just the soldier who escaped seven times, but the human being who posed—naked, unguarded, and beautiful—for reasons we may never fully know.

A Note on Queer Visibility in WWI Remembrance Culture

Photographs of nude soldiers—while rarely publicized—have existed across multiple conflicts, including World War I and World War II. Often taken in private or semi-artistic contexts, these images captured the male form not only as a symbol of strength and youth, but sometimes as an intimate keepsake, a personal act of vulnerability, or even a quiet expression of queer desire. Though such photographs were uncommon, they remind us that behind every uniform was a body, a story, and a complex humanity often left out of official histories.

Stories like Edgar Garland’s remind us how queer history often survives in the margins—in photographs, in letters, in quiet acts of defiance and longing. Mainstream remembrance of World War I tends to focus on duty, sacrifice, and masculine honor, but it rarely makes space for the hidden lives of queer soldiers. Yet they were there: loving, grieving, and serving alongside their comrades. For some, like Garland, a single photograph may be the closest we get to that truth.

As we commemorate the soldiers of the Great War, it is vital to recognize that their humanity was not confined to the battlefield. Some found intimacy in silence. Some left behind coded artifacts. And some, like Garland, posed for a camera and dared to be seen—fully, tenderly, and without shame.

July 2nd, 2025 at 7:33 am

Love it! He was beautiful!Sent from my iPhone

July 2nd, 2025 at 9:20 am

I think the photographer thought the same thing. I would love to know if more was done than just photographs taken and whether the photographer took more pictures that were never allowed to be public. Whatever really happened in that studio and why will likely always be a mystery.

July 2nd, 2025 at 3:12 pm

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if a diary or something could be found

July 2nd, 2025 at 1:31 pm

The photograph of the horses bathing with naked riders was almost certainly taken at Suvla Bay or similar during the dreadful Gallipoli campaign in 1915. [A brilliant stategic campaign proposed by Churchill to knock the Ottermans out of the war, but very poorly executed by third rate British senior officers who were far too old and inexperienced for such an operation. All the better quality ones were on the Western Front.]

I run a small military museum and we have a magnificent painting titled “Watering the Horses” with three naked riders. It was always assumed that this was artistic licence, but further research shows that this is exactly how the horses and soldiers cooled down. In those old days male nudity was commonplace out of sight of the ladies. I don’t suppose there were many ladies at Suvla Bay, excepting the brave nurses, and they would have seen everything.

July 2nd, 2025 at 2:24 pm

It is a picture from the Gallipoli campaign. There are many photos of nude men in the ANZAC archives from the Gallipoli.

I also work at a military history museum. If you ever need an educator and can pay well, I’d be interested. While we aren’t strictly a military history museum, by circumstances of our collection, that’s pretty much what we are.

July 2nd, 2025 at 4:07 pm

A spectacular historical review and point of fascination. We’ve always been and will be. No matter the policy of the eras.

September 23rd, 2025 at 4:01 pm

Wondering if anyone has ever seen these photographs reproduced anywhere? I have another WWI nude soldier postcard on my wishlist so if anyone has any other suggestions for that I’d love to hear from you. Dane