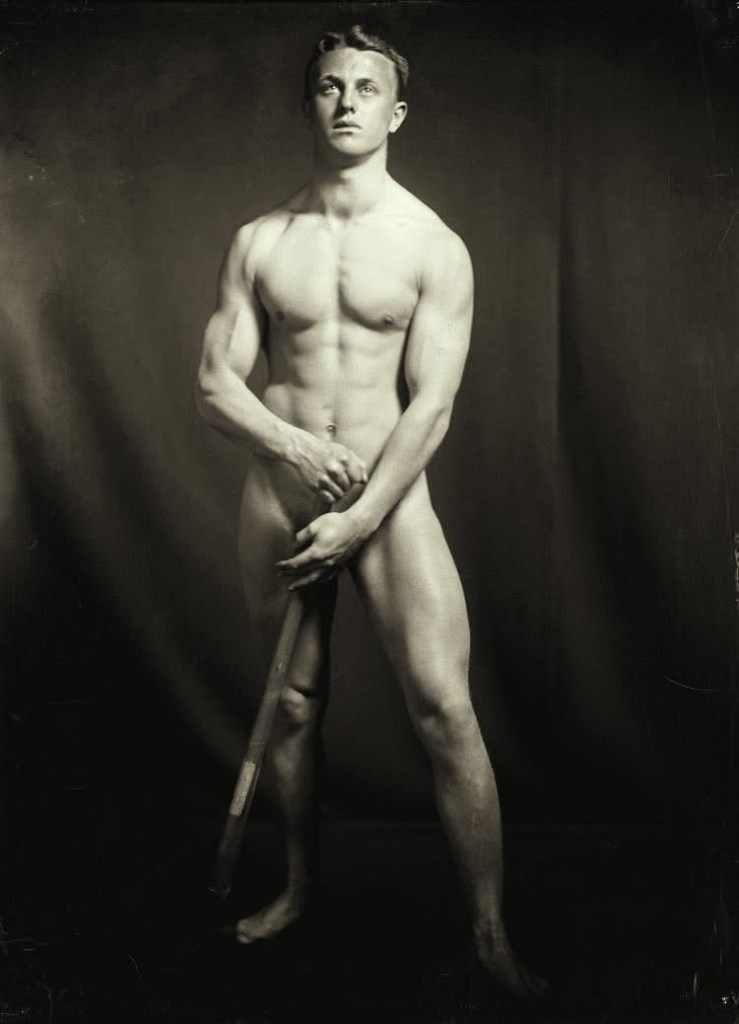

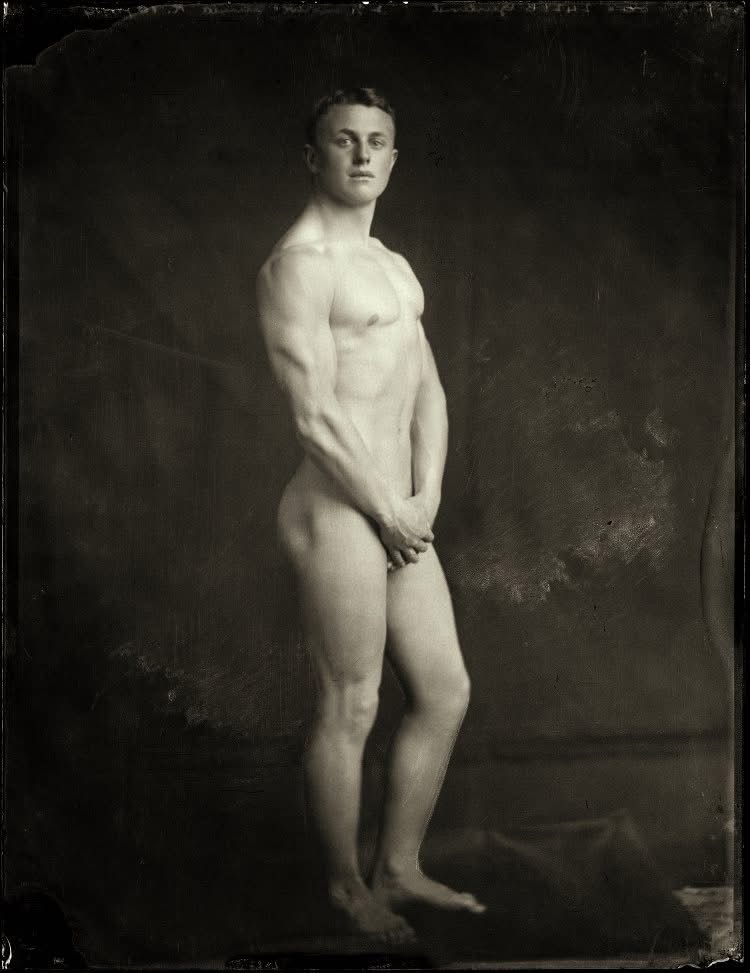

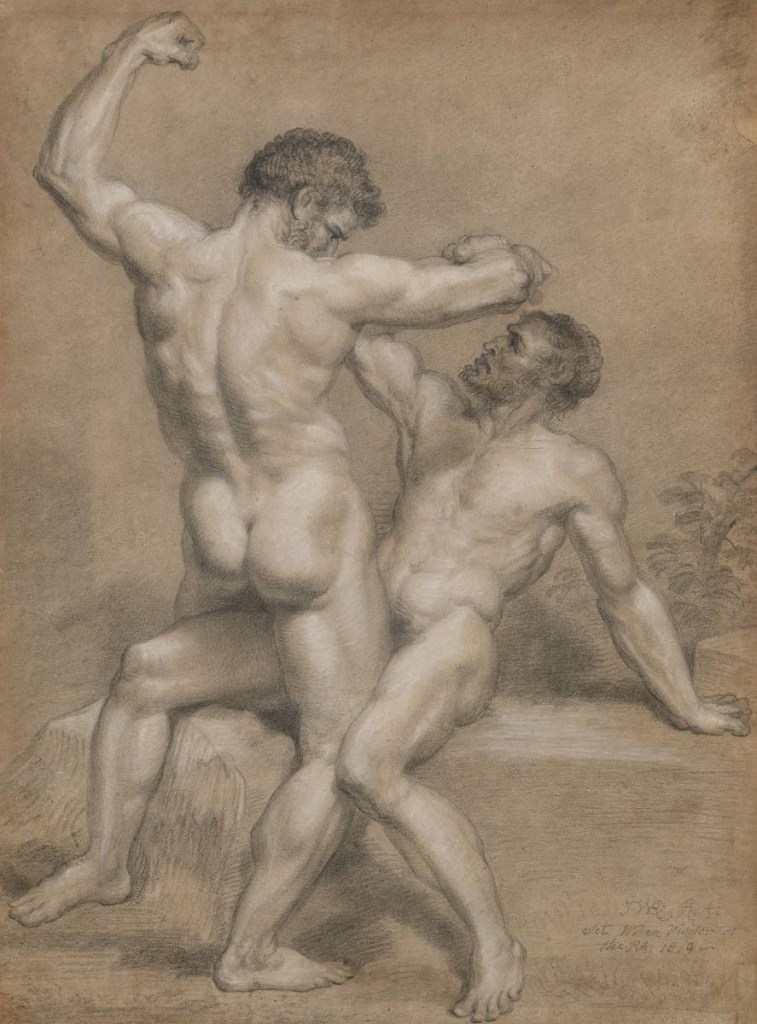

James Ward

1819

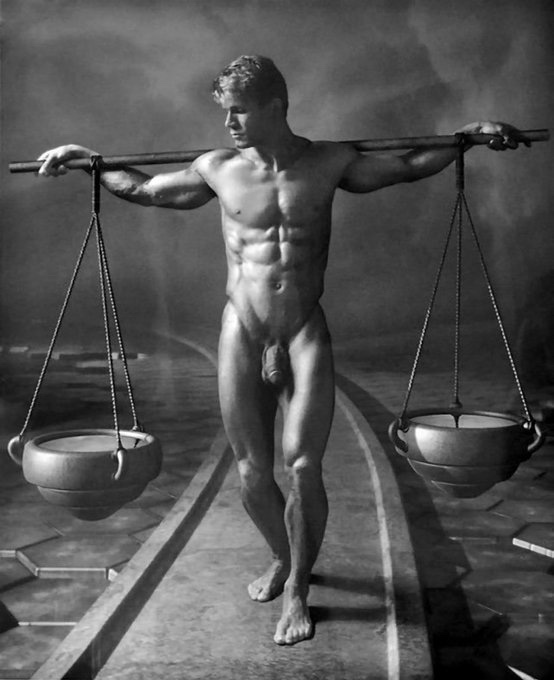

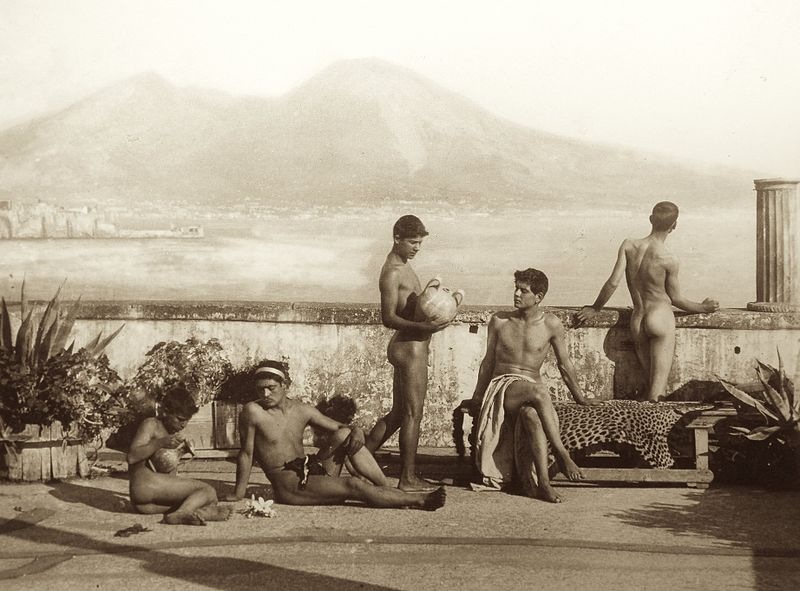

I’ve always been fascinated by how the Ancient Greeks embraced the naked body—especially the male form—not as something shameful, but as something worthy of admiration, celebration, and even reverence. To modern eyes, the sheer number of nude statues and painted vases from the ancient world might seem excessive or erotic (and sometimes, they are), but to the Greeks, nudity wasn’t just about sex. It was about excellence, identity, citizenship, and being fully human.

They didn’t just tolerate public nudity in certain settings—they expected it. Athletes competed fully nude in the Olympic Games, not as a rebellious act, but as a deeply held tradition. The word gymnasium itself comes from the Greek gymnos(γυμνός), meaning “naked.” Young men trained in the nude not just to strengthen their bodies, but to shape their minds and characters. The gymnasium was a civic and educational space where nudity signaled discipline, honesty, and a commitment to becoming the best version of oneself. Nudity wasn’t a distraction—it was part of the lesson.

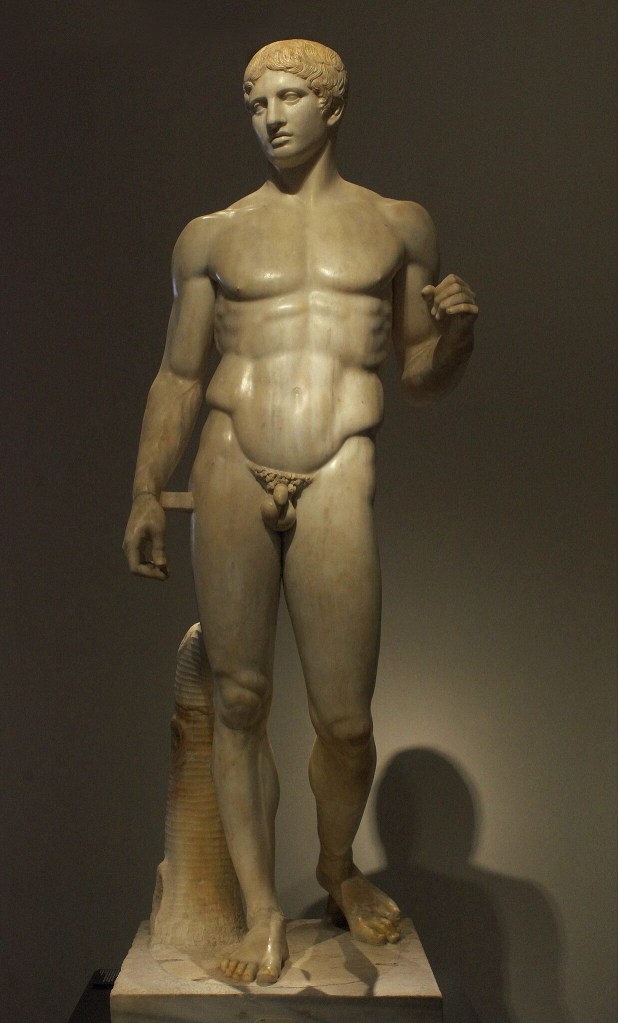

And that reverence for the human form found its most lasting legacy in art. One of the earliest and most striking examples is the Kritios Boy (c. 480 BCE), often seen as the turning point in Greek sculpture. Unlike the stiff, idealized youth of earlier kouros figures, the Kritios Boy is relaxed, confident, and lifelike. There’s no armor, no toga, no fig leaf—just a serene, nude adolescent standing in gentle contrapposto. He feels both real and ideal.

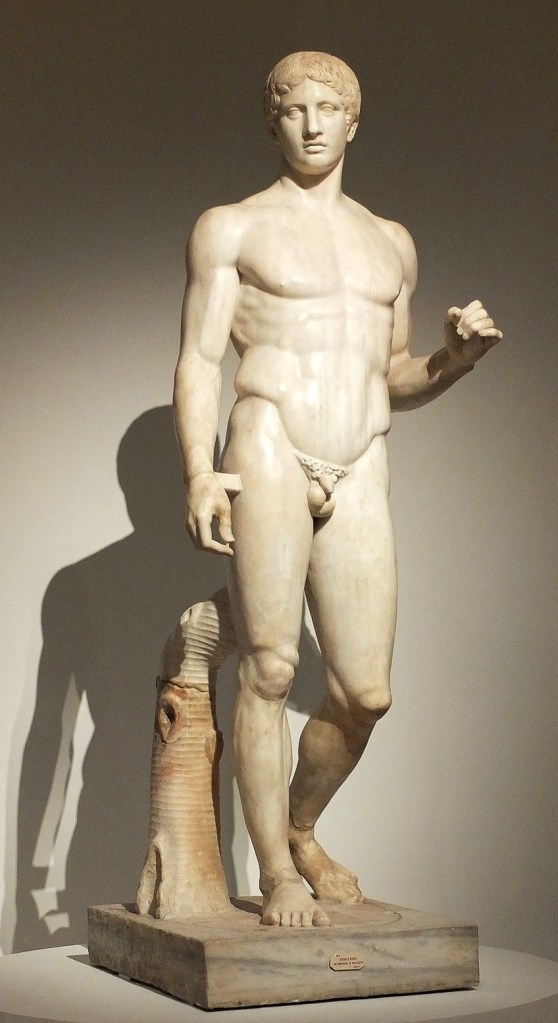

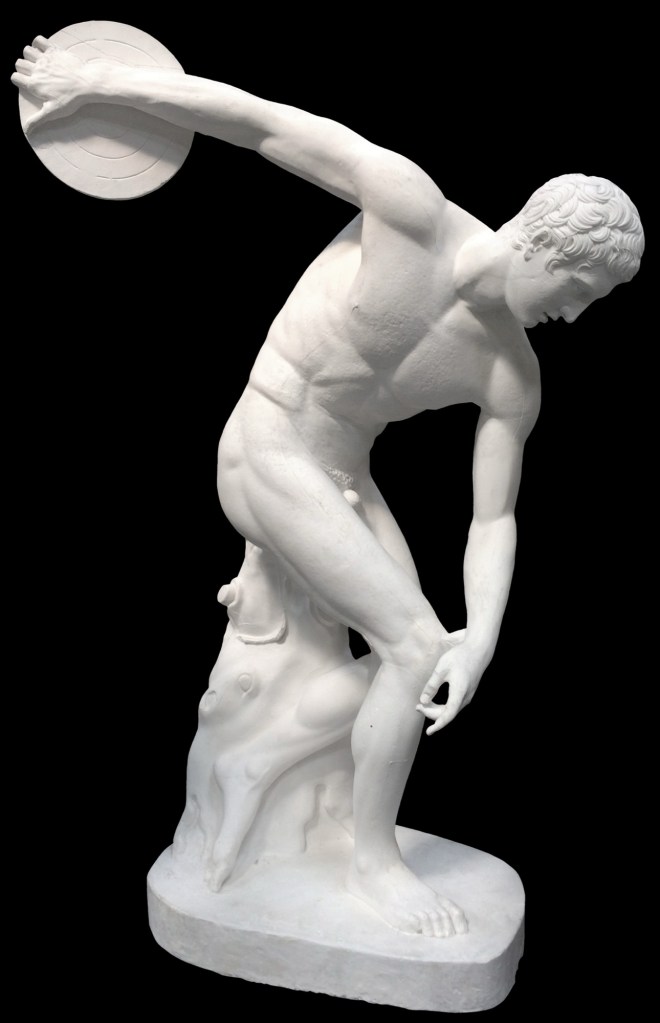

Another favorite of mine is Polykleitos’s Doryphoros (Spear Bearer), a statue designed to embody the perfect male proportions. Here again, the nudity isn’t incidental—it’s essential. You can’t demonstrate bodily harmony if the body is covered. Nudity, in this case, is a kind of visual philosophy. Then there’s the Discobolus (Discus Thrower) by Myron, which captures a man’s body in mid-motion, muscles taut, entirely nude, perfectly balanced between tension and grace. His nudity heightens the athletic drama and draws the viewer into that moment of perfection.

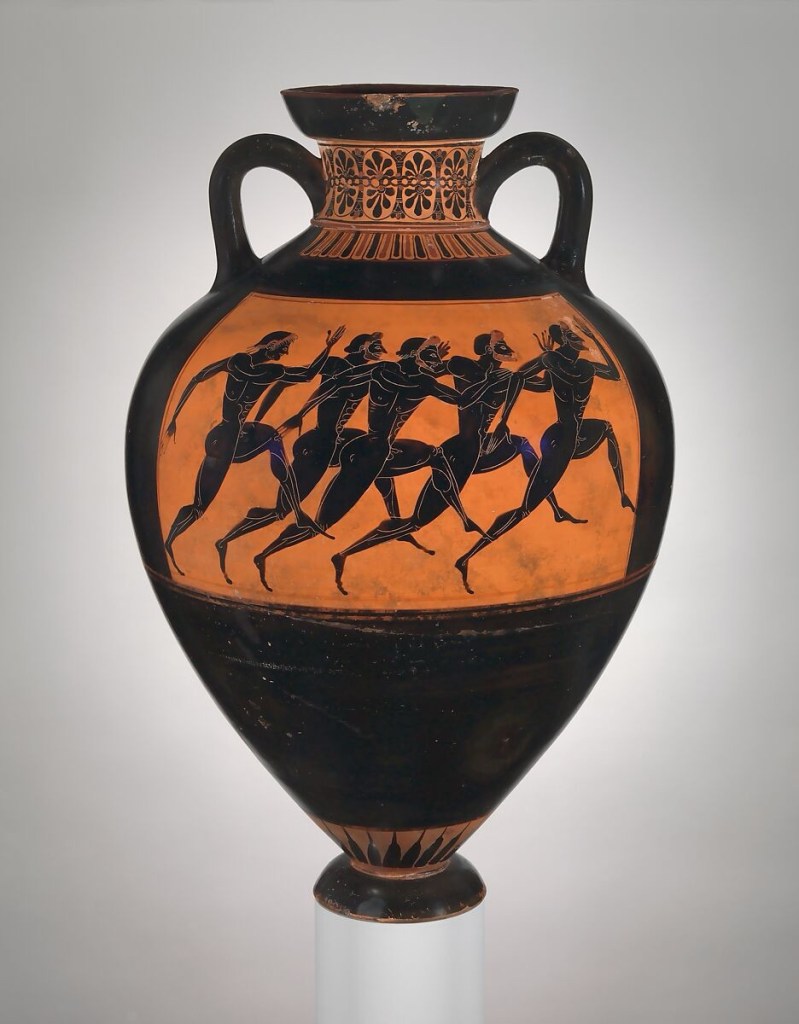

It wasn’t just in sculpture. The Greeks captured daily life, training scenes, and intimate gatherings on painted pottery, particularly in the red-figure vase tradition. These vases, often used for wine drinking at symposia, show men wrestling, bathing, reclining with lovers, and engaging in philosophical dialogue—always nude or mostly nude. One amphora I saw during a museum visit showed a trainer instructing a youth at the gymnasium, both fully exposed, their nudity treated as entirely normal, even expected. Another vase depicts two young men sharing a kiss in a quiet, domestic scene—tender, not titillating. These glimpses into Greek life are reminders that the naked body wasn’t always about arousal. Sometimes, it was about presence—being fully seen, fully known.

Attributed to the Euphiletos Painter

ca. 530 BCE

This attitude feels almost alien in a country like ours. Here in America, nudity is still largely taboo, wrapped up in Puritanical baggage and frequently equated with obscenity or indecency. Even in Vermont, where public nudity is technically legal in most cases (as long as you’re not lewd or explicitly sexual), you rarely see anyone baring it all outside of a secluded swim spot or a clothing-optional festival. There’s something quietly telling about that—how the law might allow something, but cultural discomfort still keeps it hidden.

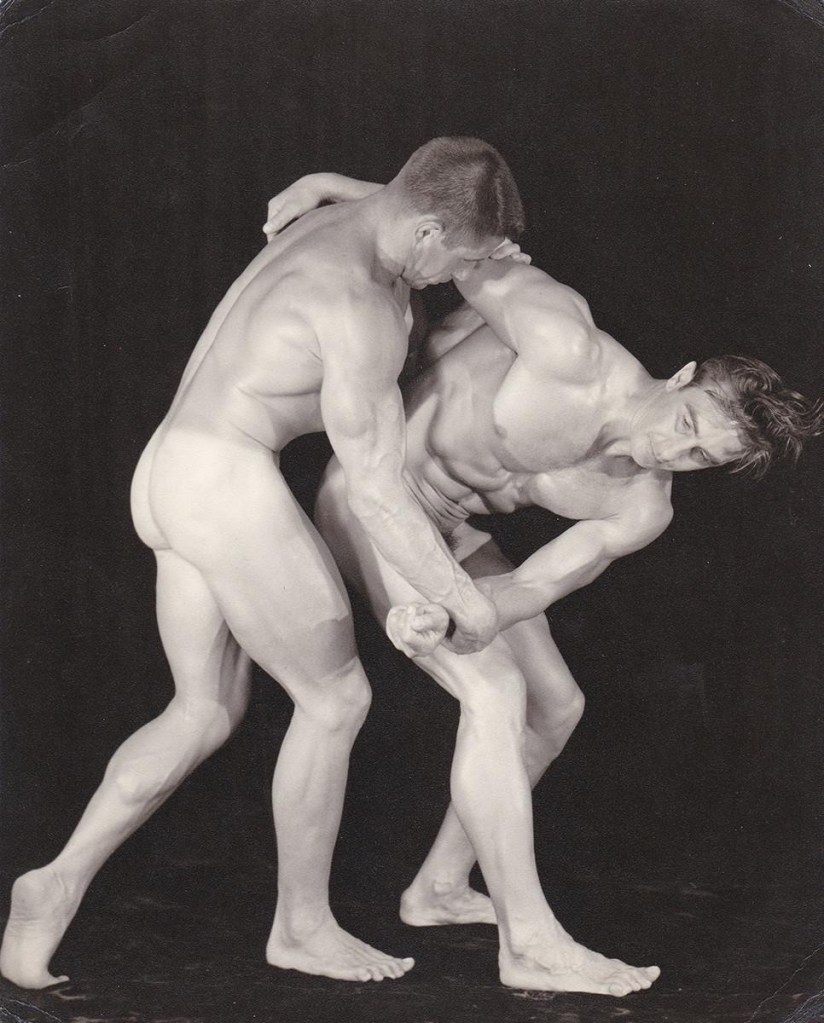

Attributed to the Theseus Painter

ca. 500 BCE

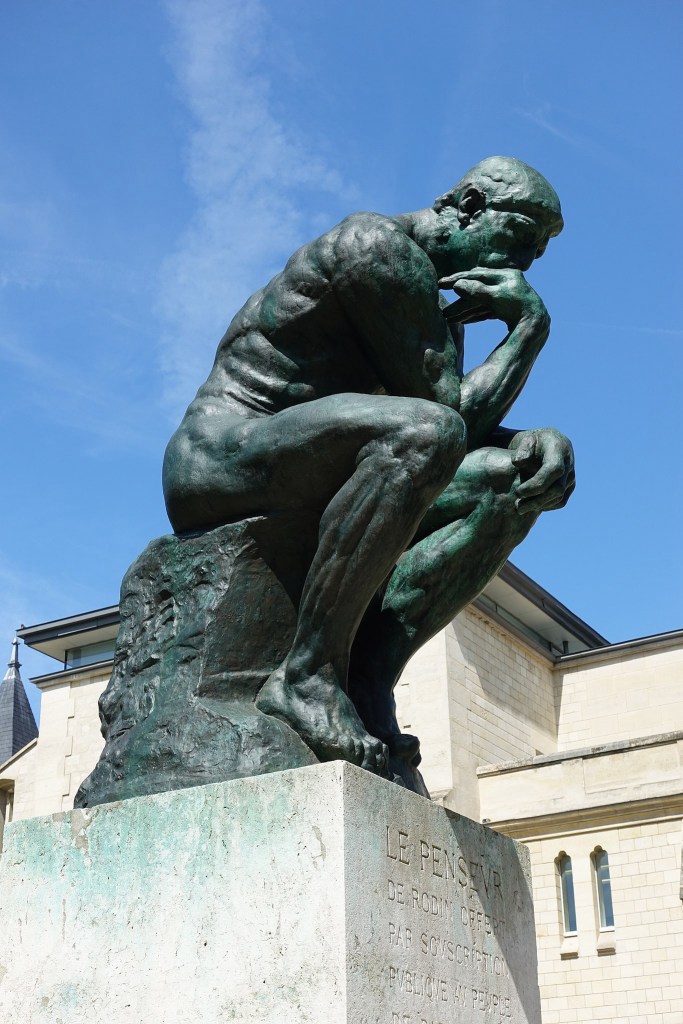

And yet, I can’t help but wonder: what would it mean if we took a more Ancient Greek view of nudity—not as something to be feared or fetishized, but as something natural, honest, even virtuous?

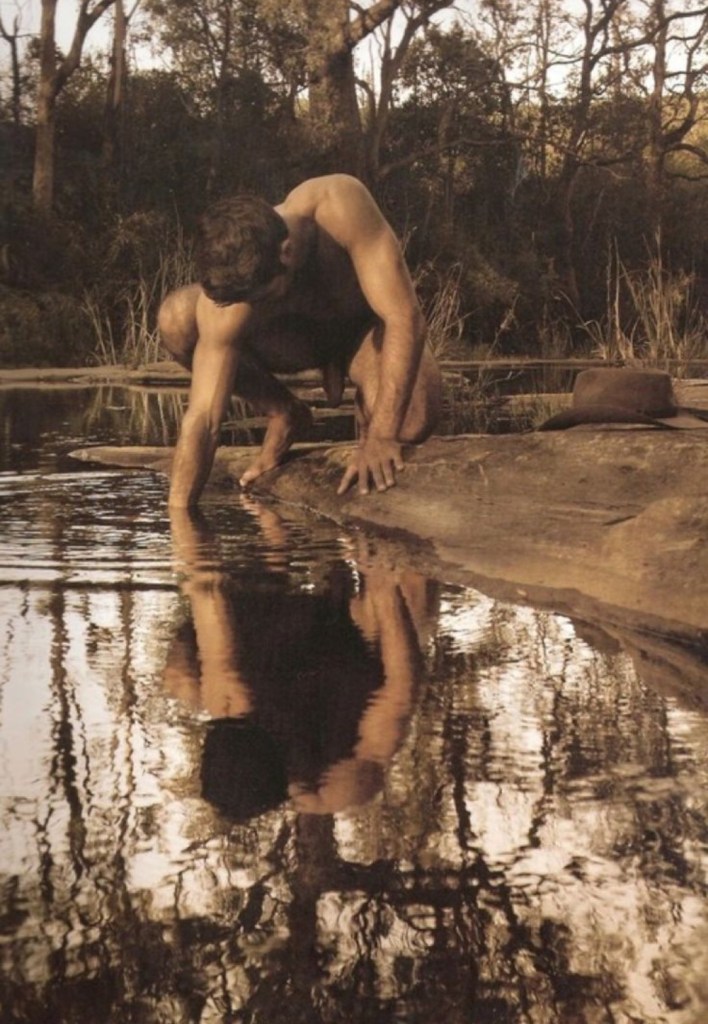

A few years ago, I attended a gay men’s retreat at Easton Mountain in upstate New York, and it gave me a real-world glimpse of what the Greeks might have understood intuitively. Nudity there wasn’t shocking or scandalous—it was completely natural. The pool was always full of naked bodies, sunlit and unselfconscious. I don’t think I ever saw a bathing suit near it. The sauna and hot tub were clothing-free zones by default, and during some of the workshops—body painting, liberation exercises, guided meditations—nudity was gently encouraged as a way to connect more honestly with ourselves and others. It wasn’t about showing off. It was about showing up. I left feeling more open, more grounded in my body, and more aware of how rare that kind of freedom really is.

It might mean raising a generation less ashamed of their bodies. It might mean allowing ourselves to admire beauty without reducing it to sex. It might mean being more comfortable in our own skin, literally and figuratively. While the Greeks didn’t extend this attitude equally—women were mostly excluded from these public displays of nudity—there’s something liberating in imagining a culture where both women and men could be nude in non-sexualized spaces without fear or judgment.

As a gay man, I think often about how visibility and embodiment intersect. For many of us, our relationship to our bodies has been shaped by shame, secrecy, and desires we were never meant to name. What if we had grown up seeing the male body—our bodies—as something to admire without guilt? What if nudity wasn’t something to hide or automatically sexualize, but something that simply was? Would we be more honest? Kinder to ourselves? More connected to one another? Might we even find ourselves a little closer to the divine—just as the Ancient Greeks did, in their reverence for the human form and their gods?