This week we turn from the visual arts to the literary, continuing our discussion of Herman Melville with a closer look at his haunting final work, Billy Budd, Sailor.

Herman Melville’s Billy Budd, Sailor (published posthumously in 1924) is, on the surface, a moral tragedy about innocence destroyed by rigid authority. Yet for many readers—especially in LGBTQ+ literary studies—it has long carried unmistakable queer undertones.

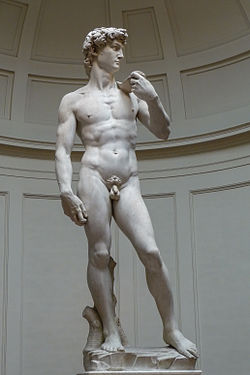

The novella tells the story of Billy Budd, the “Handsome Sailor,” whose beauty and innocence win the admiration of nearly everyone on board the Bellipotent. But his very perfection provokes the envy of John Claggart, the ship’s master-at-arms. Claggart’s obsession with Billy has been widely read as coded desire—an attraction so repressed that it curdles into destructive malice. When Claggart accuses Billy of mutiny, and Billy’s stammer leaves him unable to defend himself, Billy lashes out and strikes him dead. Captain Vere, though he believes in Billy’s essential innocence, insists on enforcing naval law, and Billy is executed.

This framework—an innocent young man destroyed not by his own fault but by the inability of others to reckon with their own desires—fits squarely within a long tradition of queer literature. For centuries, queer-coded characters in fiction have met tragic ends: death, exile, madness, or erasure. From Carmilla to The Well of Loneliness, from coded Hollywood films of the mid-20th century to countless novels well into the late 20th century, queer lives were depicted as doomed. The rare exception—stories offering queer joy and fulfillment—did not become more common until the 21st century. Read in this light, Billy Budd becomes more than a moral allegory; it is part of this larger pattern, a queer tragedy written before the word “queer” had the meaning we give it today.

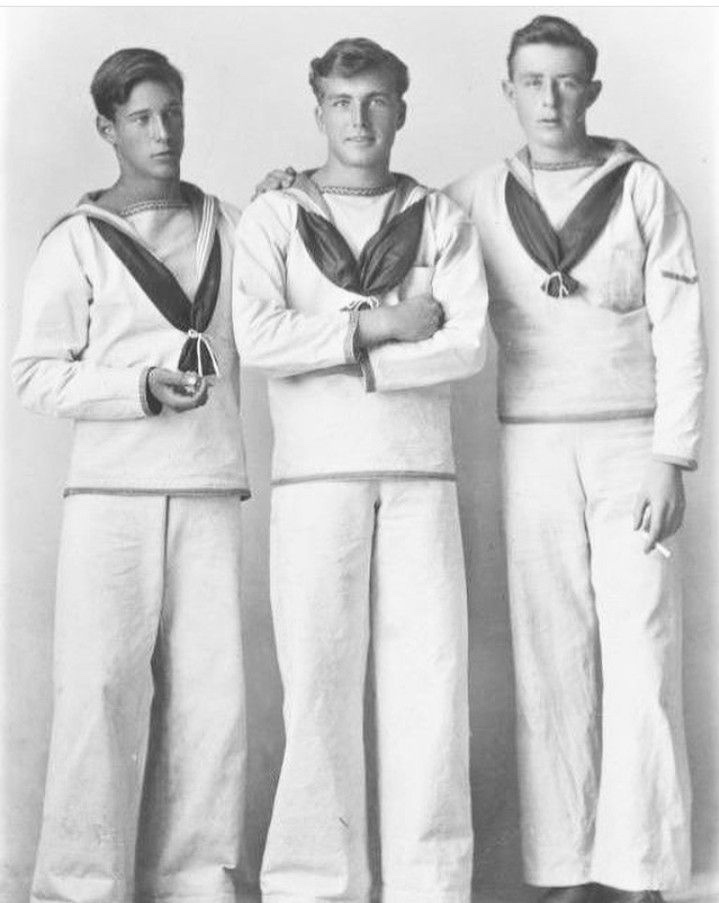

It is not only the text that invites this reading, but also the life of the author himself. Herman Melville (1819–1891) wrote with unusual intensity about male beauty and intimacy, often setting his stories in all-male environments—ships, armies, or remote islands. His close friendship with Nathaniel Hawthorne produced letters of remarkable passion, describing a “sweet mystery” and “infinite fraternity” that some scholars have read as expressions of romantic love. While we cannot say with certainty what Melville’s own sexuality was, his works consistently return to themes of male closeness, desire, and repression.

That is why Billy Budd continues to resonate. It is a story of desire unnamed, beauty destroyed, and innocence sacrificed to rigid authority. Billy’s calm acceptance of his fate, his blessing of Captain Vere even as he goes to his death, echoes the countless queer characters who, in fiction and in history, have borne the cost of a society unwilling to recognize the fullness of their humanity.

I have not returned to Billy Budd, Sailor since first reading it in college, because it left me with an unsettling feeling and a profound sadness. Billy is pressed unwillingly into service, yet he performs his duty faithfully. He is beloved for both his sweetness and his beauty, but his flaw—his speech impediment—ultimately seals his fate. Having struggled with a speech impediment myself as a child, that aspect of his character resonated deeply. So too did the queer subtext. The tragedy in Billy Budd does not lie in Billy’s own sexuality, but in the repressed same-sex desires of others. I have often wondered whether Billy may have been subjected to unwanted advances, whether he resisted them, or whether it was simply the intensity of others’ unacknowledged longing for him that condemned him. His Christ-like depiction suggests that he does not die for his own sins, but rather as a sacrifice demanded by the sins of those around him.

That is what has always made the story so unsettling for me: Billy’s destruction comes not from his own flaws, but from the world’s inability to deal honestly with desire. In that sense, Melville’s novella anticipates the tragic arc of so much queer literature to follow, where beauty, love, or innocence is sacrificed to repression and fear. And yet, reflecting on Billy Budd today, I take some comfort in knowing how far literature has come. We now have stories that celebrate queer joy and resilience, stories where love does not have to end in silence or the grave. Wrestling with Melville’s tragic vision honors the past, but telling and living new stories of survival and fulfillment blesses the future.