Last night, I had a bit of a sinus headache, so I took some NyQuil to help me sleep and to take care of the headache and sinus problems. It worked, but I slept nearly all day. Now I have the Blahs, I don’t feel like putting together a post, so this is all there will be today. I had a post in mind, but I will do that one for tomorrow.

Category Archives: Nudity

Barefoot in the Summer

|

| Chestnuts, Burrs, and Leaves |

In honor of the official beginning of summer (though with this heat it has been here for a while now), I want to start off my summer poetry series with two poems about being barefoot. As a child of the South, we rarely ever played outside without being barefoot. Shoes were worn when we were going somewhere or when company was coming. I do remember one time when I truly wished I had not been barefoot. My grandparents had a chestnut tree. I don’t know how many of you are familiar with chestnut trees, but chestnuts grow inside burrs (see the picture on the right), which look like little porcupines. A group of us kids were playing around the chestnut tree, climbing it and fooling around. Stupidly we were barefoot, but being barefoot made climbing a tree easier. When we were down on the ground, I was backing up (I think my sister was threatening me). I stepped on one of these burrs. Hundreds of the little thorns went into the bottom of my foot. It took my grandfather and father all day and much of the night to get most of them out. A few that got really embedded in my foot didn’t come out for months and sometimes even years. It was not one of my finer moments.

|

| Chestnut Tree |

So in honor of those barefoot days of summer, here are some poems that I hope you will enjoy.

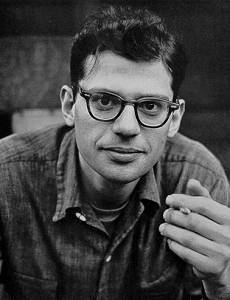

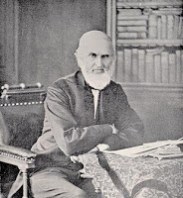

The Barefoot Boy by John Greenleaf Whittier

Barefoot Days by Rachel Field

|

| John Greenleaf Whittier |

Moment of Zen: The Pineapple

I remembered learning this at a tour of a plantation: When guest would come over to spend a few days, they were greeted with a pineapple. But if they over stayed their welcome, they would find half a pineapple at the foot of their bed. This was an unspoken signal that it was time for them to leave.

Thank goodness, the guy in the picture above seems to be welcoming us.

Text Source: http://EzineArticles.com/1044420

Rugby: Homoerotic?

The Sonnets

![palm copy[3] palm copy[3]](https://i0.wp.com/lh4.ggpht.com/-sjiN_dWoFOw/Te0mpHGGZ8I/AAAAAAAAb8Q/klu_1_5d_tk/palm%252520copy%25255B3%25255D_thumb%25255B5%25255D.jpg)

As I stated to Ace in a comment about last week’s poem, sonnets are my favorite form of poetry. The rhythm and cadence of a sonnet is pure beauty. I wanted to share with you today my two favorite sonnets.

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? (Sonnet 18)

by William Shakespeare

![2718_01[3] 2718_01[3]](https://i0.wp.com/lh4.ggpht.com/-3EhV2CLwSOA/Te0mrZOZRJI/AAAAAAAAb8Y/DIuZ8sCZNyc/2718_01%25255B3%25255D_thumb%25255B4%25255D.jpg) Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer's lease hath all too short a date.

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature's changing course, untrimmed;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st,

Nor shall death brag thou wand'rest in his shade,

When in eternal lines to Time thou grow'st.

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.How Do I Love Thee? (Sonnet 43)

by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

![aint heavy[3] aint heavy[3]](https://i0.wp.com/lh3.ggpht.com/-8bXCDuFXSR4/Te0mtbNkyVI/AAAAAAAAb8g/efAPklLSXW0/aint%252520heavy%25255B3%25255D_thumb%25255B3%25255D.jpg) How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day's

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right.

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood's faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

What is your favorite form of poetry?What is your favorite poem?Sonnets from the PortugueseShakespeare's Sonnets

Moment of Zen: Getting Lost…

…in another world, as only books can take you. Whether it is a great classic, a trashy summer read, a bestselling thriller, fiction/non-fiction, it doesn’t matter. A well-written book can transport us to another world, one that lives in the imagination of the writer and reader or one that is a past gone by (I had to throw in the last one as a historian, LOL).

Travelling Between Places

TRAVELLING BETWEEN PLACES

![]() Leaving nothing and nothing ahead;

Leaving nothing and nothing ahead;

when you stop for the evening

the sky will be in ruins,

when you hear late birds

with tired throats singing

think how good it is that they,

knowing you were coming,

stayed up late to greet you

who travels between places

when the late afternoon

drifts into the woods, when

nothing matters specially.

BRIAN PATTEN

Born near Liverpool’s docks, he attended Sefton Park School in the Smithdown Road area of Liverpool, where he was noted for his essays and greatly encouraged in his work by Harry Sutcliffe his form teacher. He left school at fifteen and began work for The Bootle Times writing a column on popular music. One of his first articles was on Roger McGough and Adrian Henri, two pop-oriented Liverpool Poets who later joined Patten in a best-selling poetry anthology called The Mersey Sound, drawing popular attention to his own contemporary collections Little Johnny’s Confession (1967) and Notes to the Hurrying Man (1969). Patten received early encouragement from Philip Larkin.

Patten’s style is generally lyrical and his subjects are primarily love and relationships. His 1981 collection Love Poems draws together his best work in this area from the previous sixteen years. Tribune has described Patten as “the master poet of his genre, taking on the intricacies of love and beauty with a totally new approach, new for him and for contemporary poetry.” Charles Causley once commented that he “reveals a sensibility profoundly aware of the ever-present possibility of the magical and the miraculous, as well as of the granite-hard realities. These are undiluted poems, beautifully calculated, informed – even in their darkest moments – with courage and hope.”

U.S. Navy Pre-Flight School, St. Mary’s, California

The Christian Brothers who moved the College to Moraga in 1928 would scarcely recognize today’s Contra Costa County, with its crowded freeways and sprawling subdivisions in place of the orchards and pastures that once dominated the landscape.

The Christian Brothers who moved the College to Moraga in 1928 would scarcely recognize today’s Contra Costa County, with its crowded freeways and sprawling subdivisions in place of the orchards and pastures that once dominated the landscape.

Moraga itself, which has grown to a population of 16,000, maintains much of the bucolic charm that enticed the Brothers from Oakland’s Broadway and 30th Street eight decades ago. Yet the surrounding East Bay has experienced an almost continuous real estate boom — especially when World War II’s military mobilization and industrialization transformed the region.

The war certainly had a dramatic impact on the College, as the U.S. Navy’s Pre-Flight School took over most of the campus at 1928 St. Mary’s Road from 1942 to 1946. The arrival of thousands of Navy men housed in temporary barracks and trained in classrooms also brought a crucial missing ingredient to Saint Mary’s — a reliable supply of water that has allowed the College to expand ever since.

The Move to Moraga

As the College started outgrowing the Oakland Brickpile campus after World War I, trains and automobiles were making it easier to settle in outlying parts of the Bay Area. In 1919, the Brothers purchased what seemed to be an ideal new location: 255 acres next to Lake Chabot in the San Leandro hills.

As the College started outgrowing the Oakland Brickpile campus after World War I, trains and automobiles were making it easier to settle in outlying parts of the Bay Area. In 1919, the Brothers purchased what seemed to be an ideal new location: 255 acres next to Lake Chabot in the San Leandro hills.

Unable to raise enough money for construction, the Brothers turned their attention elsewhere. In 1927, James Irvine’s Moraga Company — hoping a college would jumpstart real estate development — offered the Brothers 100 free acres, the beginnings of today’s 420-acre campus.

The Moraga location had many virtues — pastoral seclusion, rolling hills and plenty of elbow room — but it lacked a dependable water source. While the proposed San Leandro site was on a lake, the Moraga location was fed solely by the fickle flow from Las Trampas Creek through a marshy area north of campus.

“It’s amazing to me that the College was able to survive here for years without other sources of water,” says biology professor Lawrence Cory, a Saint Mary’s student in the 1930s. “Some years, there might be enough water, but what about years like this one (2007) when the creek is completely dry?”

In fact, Moraga developed more slowly than its neighbors because Lafayette and Orinda were situated along the aqueduct system created by the East Bay Municipal Utility District (EBMUD) in the late 1920s. EBMUD, a public trust set up in 1923 to develop a steady water supply for East Bay communities, piped Mokelumne River water to reservoirs, including the Lafayette Reservoir, by 1929. But Moraga was too far away and too small, even with the arrival of more than 200 Saint Mary’s students in 1928, to merit the effort and expense of EBMUD incorporation.

This lack of water hindered early Moraga development efforts, as Nilda Rego chronicles in her history Days Gone By in Contra Costa County. In 1922, when the county and Irvine’s company split the cost of a “Moraga Highway” from Orinda — today’s Moraga Way from Highway 24 into the town — the project almost foundered due to lack of water.

E.E. O’Brien, the Martinez contractor who won the bid, had her crews implement creative solutions to the problem.

“They told me there would be many difficulties and said I could not get the water to mix concrete for one thing,” she told the Contra Costa Courier on May 8, 1922. “Water was obtained by impounding dams along the right of way, thereby conserving the rainwater that otherwise would have run off.”

Necessity: Mother of Invention

During their first years in often-arid Moraga, the Brothers relied on similar improvisations to keep the College hydrated.

During their first years in often-arid Moraga, the Brothers relied on similar improvisations to keep the College hydrated.

As they began setting up the College in 1927, however, lack of water did not appear to be a problem. If anything, there seemed to be an abundance.

With heavy rainfall in 1927 and 1928, the campus was often flooded, slowing construction. Las Trampas Creek frequently overran its banks, rainwater flowed down from the hills and the campus’ adobe soil turned to thick mud.

One of the College’s oldest Moraga alums, Bob McAndrews ’32, remembers his first year at the College as particularly muddy: “We had to slog between buildings in boots because roads and pathways weren’t finished and the winter was exceptionally rainy.”

The soggy beginning failed to dampen the Brothers’ spirits. They lived in an era marked by new confidence in water management feats similar to EBMUD’s successful dam and pipeline system. William Mulholland’s aqueducts had brought water hundreds of miles south to thirsty Los Angeles and earthquake-shaken San Francisco dammed faraway Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite for a reliable water supply. The Brothers were convinced Las Trampas Creek could make a big enough reservoir to supply the College.

So Lake Lasalle, created with a $100,000 earthen dam constructed by Berkeley contractor J.P. Brennan, was formed. The College’s main source of water from 1928 to 1942, the 134-acre-foot reservoir was north of the campus (behind the Power Plant) at the mouth of Bollinger Canyon.

Wells supplied some of the College’s water, but Lake Lasalle provided the rest, including irrigation water for the campus’ 20 acres of lawns. A pumping station sent lake water to redwood storage tanks located in the hills behind De La Salle Hall (near today’s “SMC” logo). The College also set up a treatment system in the hills for purifying and chlorinating water.

The water tanks proved to be an irresistible target for some pranksters: At the height of the Saint Mary’s–Cal football rivalry in the early 1930s, Berkeley students tried to paint a big yellow Cal “C” on them before games.

For a while, the water system did more than quench the campus’ thirst. The lake itself was an added attraction, as students swam and boated there in the 1930s. A 1939 Gael yearbook writer rhapsodized: “Lake Lasalle, limpid, cool, inviting, where many an hour is whiled away in an easy jaunt around the mossy banks … a tranquil panorama of water, sky and rolling hills to soothe the weary eye escaping from the printed word.”

Soon enough, however, this aquatic idyll faced a significant problem — the steady accretion of silt due to erosion which threatened to overwhelm the lake.

The Brothers’ own ad hoc hydraulic engineer, Brother Nivard Raphael, took matters into his own hands. In 1941, he built a small foredam to catch silt upstream from Lake Lasalle. But Las Trampas Creek uprooted it, leaving him back at square one. He later attempted to use the sump valve that contractors built into the bottom of the lake to drain silt through an underground pipe. The valve failed, and much of the lake’s water was lost.

These efforts to revitalize Lake Lasalle were soon overshadowed by a more pressing national concern: preparation for World War II.

A Navy Needs Water

With an acute shortage of fighter pilots after Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy set up pre-flight training schools at colleges across the country. Naval officials considered several West Coast locations before accepting Saint Mary’s offer of its Moraga campus.

In a brusque wartime communication, Navy Secretary Frank Knox informed Brother President Austin via telegram on Feb. 27, 1942, that “St. Mary’s College has been selected by the Navy Department as one of the four locations for pre-flight training. Your patriotic cooperation in this vital program is appreciated.”

By June 1942, the campus’ population swelled from around 300 to more than 2,000 — the vast majority of whom were navy cadets and officers.

With a pre-flight curriculum that included boxing and swimming rather than Greek and Latin, certain accommodations were necessary. Major construction projects — including temporary barracks, a field house and a rifle range — were completed with lightning speed.

The Navy pumped silt from the bottom of Lake Lasalle to level out the area between the Chapel and St. Mary’s Road for athletic fields. The College still uses some of this space for rugby and soccer fields.

But Lake Lasalle itself, the Navy concluded, was not a good primary source of water, especially during a drought.

“When the Navy came here, they were determined not to have to rely on a creek,” Cory explains.

The College was still outside EBMUD’s service area. But while the utility district could turn down the Brothers’ request to run water pipes to Moraga, it couldn’t say no to Uncle Sam.

“The Navy went to EBMUD and told them to bring in water,” says Brother Raphael Patton, the College’s unofficial historian. “The response — that it was too far and too expensive — was what had denied the College a water connection since 1928. The Navy did not take this response kindly.”

Top Navy brass made it clear that water for the College was crucial to the war effort. Admiral L.E. Denfield sent a telegram about it to the Joint Army and Navy Munitions Board Priorities Division on May 12, 1942:

“To provide adequate water supply, both for drinking purposes and for fire protection, a pipeline will have to be constructed. The subject school (Saint Mary’s) is scheduled to open June 11, 1942, and accordingly it is requested that proper rating be assigned to the College as soon as possible.”

Rear Admiral Randall Jacobs, the chief of naval personnel responsible for overall manpower readiness, followed up with another telegram.

A few months later, EBMUD and the College made an agreement leading to the installation of iron pipe beneath St. Mary’s Road to the closest EBMUD water main (two miles away, near the intersection of Rheem Boulevard and Moraga Road) and pumping equipment to bring 200,000 gallons a day to the College.

With access to EBMUD’s Mokelumne River water established, the Navy trained thousands of pilots for action against the Axis powers. After the war, it left behind the water infrastructure that has allowed the College to grow over the last six decades.

Following years of improvisation and praying for rain, the College’s water supply was finally resolved — no more relying on Lake Lasalle, which gradually turned into a willow-covered wetland.

Source for text: http://www.stmarys-ca.edu/news-and-events/saint-marys-magazine/archives/v28/sp08/features/01.html