Androgyne, Mon Amour

BY TENNESSEE WILLIAMS

I

Androgyne, mon amour,

brochette de coeur was plat du jour,

(heart lifted on a metal skewer,

encore saignante et palpitante)

where I dined au solitaire,

table intime, one rose vase,

lighted dimly, wildly gay,

as, punctually, across the bay

mist advanced its pompe funèbre,

its coolly silvered drift of gray,

nightly requiem performed for

mourners who have slipped away…

Well, that’s it, the evening scene,

mon amour, Androgyne.

Noontime youths,

thighs and groins tight-jean-displayed,

loiter onto Union Square,

junkies flower-scattered there,

lost in dream, torso-bare,

young as you, old as I, voicing soundlessly

a cry,

oh, yes, among them

revolution bites its tongue beneath its fiery

waiting stare,

indifferent to siren’s wail,

ravishment endured in jail.

Bicentennial salute?

Youth made flesh of crouching brute.

(Dichotomy can I deny of pity in a lustful eye?)

II

Androgyne, mon amour,

shadows of you name a price

exorbitant for short lease.

What would you suggest I do,

wryly smile and turn away,

fox-teeth gnawing chest-bones through?

Even less would that be true

than, carnally, I was to you

many, many lives ago,

requiems of fallen snow.

And, frankly, well, they’d laugh at me,

thick of belly, thin of shank,

spectacle of long neglect,

tragedian of public mirth.

(Chekhov’s Mashas all wore black

for a reason I suspect:

Pertinence? None at all—

yet something made me think of that.)

“Life!” the gob exclaimed to Crane,

“Oh, life’s a geyser!”

Oui, d’accord—

from the rectum of the earth.

Bitter, that. Never mind.

Time’s only challenger is time.

III

Androgyne, mon amour,

cold withdrawal is no cure

for addiction grown so deep.

Now, finally, at cock’s crow,

released in custody of sleep,

dark annealment, time-worn stones

far descending,

no light there, no sound there,

entering depths of thinning breath,

farther down more ancient stones,

halting not, drawn on until

Ever treacherous, ever fair,

at a table small and square,

not first light but last light shows

(meaning of the single rose

where I dined au solitaire

sous l’ombre d’une jeunesse perdue?)

A ghostly little customs-clerk

(“Vos documents, Mesdames, Messieurs?”)

whose somehow tender mockery

contrives to make admittance here

at this mineral frontier

a definition of the pure…

Androgyne, mon amour.

“Androgyne, Mon Amour” by Tennessee Williams, from THE COLLECTED POEMS OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS, copyright © 1937, 1956, 1964, 2002 by The University of the South. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Source: THE COLLECTED POEMS OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS (New Directions Publishing Corporation, 2002)

For more about Tennessee Williams, Click on “Read More” below.

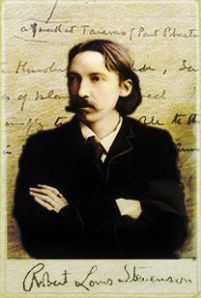

Tennessee Williams

The production of his first two Broadway plays, The Glass Menagerie and A Streetcar Named Desire, secured Tennessee Williams’s place, along with Eugene O’Neill and Arthur Miller, as one of America’s major playwrights of the twentieth century. Critics, playgoers, and fellow dramatists recognized in Williams a poetic innovator who, refusing to be confined in what Stark Young in the New Republic called “the usual sterilities of our playwriting patterns,” pushed drama into new fields, stretched the limits of the individual play and became one of the founders of the so-called “New Drama.” Praising The Glass Menagerie “as a revelation of what superb theater could be,” Brooks Atkinson in Broadway asserted that “Williams’s remembrance of things past gave the theater distinction as a literary medium.” Twenty years later, Joanne Stang wrote in the New York Times that “the American theater, indeed theater everywhere, has never been the same” since the premier of The Glass Menagerie.Four decades after that first play, C. W. E. Bigsby in A Critical Introduction to Twentieth-Century American Drama termed it “one of the best works to have come out of the American theater.” A Streetcar Named Desire became only the second play in history to win both the Pulitzer Prize and the New York Drama Critics Circle Award. Eric Bentley, in What Is Theatre?, called it the “master-drama of the generation.” “The inevitability of a great work of art,” T. E. Kalem stated in Albert J. Devlin’s Conversations with Tennessee Williams, “is that you cannot imagine the time when it didn’t exist. You can’t imagine a time when Streetcar didn’t exist.”

More clearly than with most authors, the facts of Williams’s life reveal the origins of the material he crafted into his best works. The Mississippi in which Thomas Lanier Williams was born March 26, 1911, was in many ways a world that no longer exists, “a dark, wide, open world that you can breathe in,” as Williams nostalgically described it in Harry Rasky’s Tennessee Williams: A Portrait in Laughter and Lamentation. The predominantly rural state was dotted with towns such as Columbus, Canton, and Clarksdale, in which he spent his first seven years with his mother, his sister, Rose, and his maternal grandmother and grandfather, an Episcopal rector. A sickly child, Tom was pampered by doting elders. In 1918, his father, a traveling salesman who had often been absent—perhaps, like his stage counterpart in The Glass Menagerie, “in love with long distances”—moved the family to St. Louis. Something of the trauma they experienced is dramatized in the 1945 play. The contrast between leisurely small-town past and northern big-city present, between protective grandparents and the hard-drinking, gambling father with little patience for the sensitive son he saw as a “sissy,” seriously affected both children. While Rose retreated into her own mind until finally beyond the reach even of her loving brother, Tom made use of that adversity. St. Louis remained for him “a city I loathe,” but the South, despite his portrayal of its grotesque aspects, proved a rich source to which he returned literally and imaginatively for comfort and inspiration. That background, his homosexuality, and his relationships—painful and joyous—with members of his family, were the strongest personal factors shaping Williams’s dramas.

During the St. Louis years, Williams found an imaginative release from unpleasant reality in writing essays, stories, poems, and plays. After attending the University of Missouri, Washington University—from which he earned a B.A. in 1938—and the University of Iowa, he returned to the South, specifically to New Orleans, one of two places where he was for the rest of his life to feel at home. Yet a recurrent motif in his plays involves flight and the fugitive, who, Lord Byron insists in Camino Real: A Play,must keep moving, and the flight from St. Louis initiated a nomadic life of brief stays in a variety of places. Williams fled not only uncongenial atmospheres but a turbulent family situation that had culminated in a decision for Rose to have a prefrontal lobotomy in an effort to alleviate her increasing psychological problems. (Williams’s works often include absentee fathers, enduring—if aggravating—mothers, and dependent relatives; and the memory of Rose appears in some character, situation, symbol or motif in almost every work after 1938.) He fled as well some part of himself, for he had created a new persona—Tennessee Williams the playwright—who shared the same body as the proper young gentleman named Thomas with whom Tennessee would always be to some degree at odds.

In 1940, Williams’s Battle of Angels was staged by the Theatre Guild in an ill-fated production marred as much by faulty smudge pots in the lynching scene as by Boston censorship. Despite the abrupt out-of-town closing of the play, Williams was now known and admired by powerful theater people. During the next two decades, his most productive period, one play succeeded another, each of them permanent entries in the history of modern theater: The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, Summer and Smoke, The Rose Tattoo, Camino Real, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Orpheus Descending, Suddenly Last Summer, Sweet Bird of Youth, and The Night of the Iguana. Despite increasingly adverse criticism, Williams continued his work for the theater for two more decades, during which he wrote more than a dozen additional plays containing evidence of his virtues as a poetic realist. In the course of his long career he also produced three volumes of short stories, many of them as studies for subsequent dramas; two novels, two volumes of poetry; his memoirs; and essays on his life and craft. His dramas made that rare transition from legitimate stage to movies and television, from intellectual acceptance to popular acceptance. Before his death in 1983, he had become the best-known living dramatist; his plays had been translated and performed in many foreign countries, and his name and work had become known even to people who had never seen a production of any of his plays. The persona named Tennessee Williams had achieved the status of a myth.

Williams drew from the experiences of his persona. He saw himself as a shy, sensitive, gifted man trapped in a world where “mendacity” replaced communication, brute violence replaced love, and loneliness was, all too often, the standard human condition. These tensions “at the core of his creation” were identified by Harold Clurman in his introduction to Tennessee Williams: Eight Plays as a terror at what Williams saw in himself and in America, a terror that he must “exorcise” with “his poetic vision.” In an interview collected in Conversations with Tennessee Williams, Williams identified his main theme as a defense of the Old South attitude—”elegance, a love of the beautiful, a romantic attitude toward life”—and “a violent protest against those things that defeat it.” An idealist aware of what he called in a Conversations interview “the merciless harshness of America’s success-oriented society,” he was ironically, naturalistic as well, conscious of the inaccessibility of that for which he yearned. He early developed, according to John Gassner in Theatre at the Crossroads: Plays and Playwrights of the Mid-Century American Stage,“a precise naturalism” and continued to work toward a “fusion of naturalistic detail with symbolism and poetic sensibility rare in American playwriting.” The result was a unique romanticism, as Kenneth Tynan observed in Curtains,“which is not pale or scented but earthy and robust, the product of a mind vitally infected with the rhythms of human speech.”

Williams’s characters endeavor to embrace the ideal, to advance and not “hold back with the brutes,” a struggle no less valiant for being vain. In A Streetcar Named Desire Blanche’s idealization of life at Belle Reve, the DuBois plantation, cannot protect her once, in the words of the brutish Stanley Kowalski, she has come “down off them columns” into the “broken world,” the world of sexual desire. Since every human, as Val Xavier observes in Orpheus Descending, is sentenced “to solitary confinement inside our own lonely skins for as long as we live on earth,” the only hope is to try to communicate, to love, and to live—even beyond despair, as The Night of the Iguanateaches. The attempt to communicate often takes the form of sex (and Williams has been accused of obsession with that aspect of human existence), but at other times it becomes a willingness to show compassion, as when in The Night of the IguanaHannah Jelkes accepts the neuroses of her fellow creatures and when in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Big Daddy understands, as his son Brick cannot, the attachment between Brick and Skipper. In his preface to Cat on a Hot Tin Roof Williams might have been describing his characters’ condition when he spoke of “the outcry of prisoner to prisoner from the cell in solitary where each is confined for the duration of his life.” “The marvel is,” as Tynan stated, that Williams’s “abnormal” view of life, “heightened and spotlighted and slashed with bogey shadows,” can be made to touch his audience’s more normal views, thus achieving that “miracle of communication” Williams believed to be almost impossible.

Some of his contemporaries—Arthur Miller notably—responded to the modern condition with social protest, but Williams, after a few early attempts at that genre, chose another approach. Williams insisted in a Conversations interview that he wrote about the South not as a sociologist: “What I am writing about is human nature. . . . Human relations are terrifyingly ambiguous.” Williams chose to present characters full of uncertainties, mysteries, and doubts. Yet Arthur Miller himself wrote in The Theatre Essays of Tennessee Williams that although Williams might not portray social reality, “the intensity with which he feels whatever he does feel is so deep, is so great” that his audiences glimpse another kind of reality, “the reality in the spirit.” Clurman likewise argued that though Williams was no “propagandist,” social commentary is “inherent in his portraiture.” The inner torment and disintegration of a character like Blanche in A Streetcar Named Desire thus symbolize the lost South from which she comes and with which she is inseparably entwined. It was to that lost world and the unpleasant one which succeeded it that Williams turned for the majority of his settings and material.

Like that of most Southern writers, Williams’s work exhibits an abiding concern with time and place and how they affect men and women. “The play is memory,” Tom proclaims in The Glass Menagerie; and Williams’s characters are haunted by a past that they have difficulty accepting or that they valiantly endeavor to transform into myth. Interested in yesterday or tomorrow rather than in today, painfully conscious of the physical and emotional scars the years inflict, they have a static, dreamlike quality, and the result, Tynan observed, is “the drama of mood.” The Mississippi towns of his childhood continued to haunt Williams’s imagination throughout his career, but New Orleans offered him, he told Robert Rice in the 1958 New York Post interviews, a new freedom: “The shock of it against the Puritanism of my nature has given me a subject, a theme, which I have never ceased exploiting.” (That shabby but charming city became the setting for several stories and one-act plays, and A Streetcar Named Desire derives much of its distinction from French Quarter ambience and attitudes; as Stella informs Blanche, “New Orleans isn’t like other cities,” a view reinforced by Williams’s 1977 portrait of the place in Vieux Carre.) Atkinson observed, “Only a writer who had survived in the lower depths of a sultry Southern city could know the characters as intimately as Williams did and be so thoroughly steeped in the aimless sprawl of the neighborhood life.”

Williams’s South provided not only settings but other characteristics of his work—romanticism; a myth of an Arcadian existence now disappeared; a distinctive way of looking at life, including both an inbred Calvinistic belief in the reality of evil eternally at war with good, and what Bentley called a “peculiar combination of the comic and the pathetic.” The South also inspired Williams’s fascination with violence, his drawing upon regional character types, and his skill in recording Southern language—eloquent, flowery, sometimes bombastic. Moreover, Southern history, particularly the lost cause of the U.S. Civil War and the devastating Reconstruction period, imprinted on Williams, as on such major Southern fiction writers as William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and Walker Percy, a profound sense of separation and alienation. Williams, as Thomas E. Porter declared in Myth and Modern American Drama, explored “the mind of the Southerner caught between an idyllic past and an undesirable present,” commemorating the death of a myth even as he continued to examine it. “His broken figures appeal,” Bigsby asserted, “because they are victims of history—the lies of the old South no longer being able to sustain the individual in a world whose pragmatics have no place for the fragile spirit.” In a Conversations interview the playwright commented that “the South once had a way of life that I am just old enough to remember—a culture that had grace, elegance. . . . I write out of regret for that.”

Williams’s plays are peopled with a large cast that J. L. Styan termed, in Modern Drama in Theory and Practice, “Garrulous Grotesques”; these figures include “untouchables whom he touches with frankness and mercy,” according to Tynan. They bear the stamp of their place of origin and speak a “humorous, colorful, graphic” language, which Williams in a Conversations interview called the “mad music of my characters.” “Have you ever known a Southerner who wasn’t long-winded?” he asked; “I mean, a Southerner not afflicted with terminal asthma.” Among that cast are the romantics who, however suspect their own virtues may be, act out of belief in and commitment to what Faulkner called the “old verities and truths of the heart.” They include fallen aristocrats hounded, Gerald Weales observed in American Drama since World War II, “by poverty, by age, by frustration,” or, as Bigsby called them in his 1985 study, “martyrs for a world which has already slipped away unmourned”; fading Southern belles such as Amanda Wingate and Blanche DuBois; slightly deranged women, such as Aunt Rose Comfort in an early one-act play and in the film “Baby Doll”; dictatorial patriarchs such as Big Daddy; and the outcasts (or “fugitive kind,” the playwright’s term later employed as the title of a 1960 motion picture). Many of these characters tend to recreate the scene in which they find themselves—Laura with her glass animals shutting out the alley where cats are brutalized, Blanche trying to subdue the ugliness of the Kowalski apartment with a paper lantern; in their dialogue they frequently poeticize and melodramatize their situations, thereby surrounding themselves with protective illusion, which in later plays becomes “mendacity.” For also inhabiting that dramatic world are more powerful individuals, amoral representatives of the new Southern order, Jabe Torrance in Battle of Angels, Gooper and Mae in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Boss Finley in Sweet Bird of Youth, enemies of the romantic impulse and as destructive and virtueless as Faulkner’s Snopes clan. Southern though all these characters are, they are not mere regional portraits, for through Williams’s dramatization of them and their dilemmas and through the audience’s empathy, the characters become everyman and everywoman.

Although traumatic experiences plagued his life, Williams was able to press “the nettle of neurosis” to his heart and produce art, as Gassner observed. Williams’s family problems, his alienation from the social norm resulting from his homosexuality, his sense of being a romantic in an unromantic, postwar world, and his sensitive reaction when a production proved less than successful all contributed significantly to his work. Through the years he suffered from a variety of ailments, some serious, some surely imaginary, and at certain periods he overindulged in alcohol and prescription drugs. Despite these circumstances, he continued to write with a determination that verged at times almost on desperation, even as his new plays elicited progressively more hostile reviews from critics.

An outgrowth of this suffering is the character type “the fugitive kind,” the wanderer who lives outside the pale of society, excluded by his sensitivity, artistic bent, or sexual proclivity from the world of “normal” human beings. Like Faulkner, Williams was troubled by the exclusivity of any society that shuts out certain segments because they are different. First manifested in Val of Battle of Angels (later rewritten as Orpheus Descending) and then in the character of Tom, the struggling poet of The Glass Menagerie and his shy, withdrawn sister, the fugitive kind appears in varying guises in subsequent plays, including Blanche DuBois, Alma Winemiller (Summer and Smoke), Kilroy (Camino Real), and Hannah and Shannon (The Night of the Iguana). Each is unique but they share common characteristics, which Weales summed up as physical or mental illness, a preoccupation with sex, and a “combination of sensitivity and imagination with corruption.” Their abnormality suggests, the critic argued, that the dramatist views the norm of society as being faulty itself. Even characters within the “norm” (Stanley Kowalski, for example) are often identified with strong sexual drives. Like D. H. Lawrence, Williams indulged in a kind of phallic romanticism, attributing sexual potency to members of the unintelligent lower classes and sterility to aristocrats. Despite his romanticism, however, Williams’s view of humanity was too realistic for him to accept such pat categories. “If you write a character that isn’t ambiguous,” Williams said in a Conversations interview, “you are writing a false character, not a true one.” Though he shared Lawrence’s view that one should not suppress sexual impulses, Williams recognized that such impulses are at odds with the romantic desire to transcend and that they often lead to suffering like that endured by Blanche DuBois. Those fugitive characters who are destroyed, Bigsby remarked, often perish “because they offer love in a world characterized by impotence and sterility.” Thus phallic potency may represent a positive force in a character such as Val or a destructive force in one like Stanley Kowalski; but even in A Streetcar Named DesireWilliams acknowledges that the life force, represented by Stella’s baby, is positive. There are, as Weales pointed out, two divisions in the sexual activity Williams dramatizes: “desperation sex,” in which characters such as Val and Blanche “make contact with another only tentatively, momentarily” in order to communicate; and the “consolation and comfort” sex that briefly fulfills Lady in Orpheus Descending and saves Serafina in The Rose Tattoo. There is, surely, a third kind, sex as a weapon, wielded by those like Stanley; this kind of sex is to be feared, for it is often associated with the violence prevalent in Williams’s dramas.

Beginning with Battle of Angels, two opposing camps have existed among Williams’s critics, and his detractors sometimes have objected most strenuously to the innovations his supporters deemed virtues. His strongest advocates among established drama critics, notably Stark Young, Brooks Atkinson, John Gassner, and Walter Kerr, praised him for realistic clarity; compassion and a strong moral sense; unforgettable characters, especially women, based on his keen perception of human nature; dialogue at once credible and poetic; and a pervasive sense of humor that distinguished him from O’Neill and Miller.

Not surprisingly, it was from the conservative establishment that most of the adverse criticism came. Obviously appalled by this “upstart crow,” George Jean Nathan, dean of theater commentators when Williams made his revolutionary entrance onto the scene, sounded notes often to be repeated. In The Theatre Book of the Year, 1947-1948, he faulted Williams’s early triumphs for “mistiness of ideology . . . questionable symbolism . . . debatable character drawing . . . adolescent point of view . . . theatrical fabrication,” obsession with sex, fallen women, and “the deranged Dixie damsel.” Nathan saw Williams as a melodramatist whose attempts at tragedy were as ludicrous as “a threnody on a zither.” Subsequent detractors—notably Richard Gilman, Robert Brustein, Clive Barnes, and John Simon—taxed the playwright for theatricality, repetition, lack of judgment and control, excessive moralizing and philosophizing, and conformity to the demands of the ticket-buying public. His plays, they variously argued, lacked unity of effect, clarity of intention, social content, and variety; these critics saw the plays as burdened with excessive symbolism, violence, sexuality, and attention to the sordid, grotesque elements of life. Additionally, certain commentators charged that Elia Kazan, the director of the early masterpieces, virtually rewrote A Streetcar Named Desire and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. A particular kind of negative criticism, often intensely emotional, seemed to dominate evaluations of the plays produced in the last twenty years of Williams’s life.

Most critics, even his detractors, have praised the dramatist’s skillful creation of dialogue. Bentley asserted that “no one in the English-speaking theater” created better dialogue, that Williams’s plays were really “written—that is to say, set down in living language.” Ruby Cohn stated in Dialogue in American Drama that Williams gave to American theater “a new vocabulary and rhythm,” and Clurman concluded, “No one in the theater has written more melodiously. Without the least artificial flourish, his writing takes flight from the naturalistic to the poetic.” Even Mary McCarthy, no ardent fan, stated in Theatre Chronicles: 1937-1962 that Williams was the only American realist other than Paddy Chayevsky with an ear for dialogue, knew speech patterns, and really heard his characters. There were, of course, objections to Williams’s lyrical dialogue, different as it is from the dialogue of O’Neill, Miller, or any other major American playwright. Bentley admitted to finding his “fake poeticizing” troublesome at times, while Bigsby insisted that Williams was at his best only when he restrained “over-poetic language” and symbolism with “an imagination which if melodramatic is also capable of fine control.” However, those long poetic speeches or “arias” in plays of the first twenty-five years of his career became a hallmark of the dramatist’s work.

Another major area of contention among commentators has been Williams’s use of symbols, which he called in a Conversations interview “the natural language of drama.” Laura’s glass animals, the paper lantern and cathedral bells in A Streetcar Named Desire, the legless birds of Orpheus Descending, and the iguana in The Night of the Iguana, to name only a few, are integral to the plays in which they appear. Cohn commented on Williams’s extensive use of animal images in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof to symbolize the fact that all the Pollitts, “grasping, screeching, devouring,” are “greedily alive.” In that play, Big Daddy’s malignancy effectively represents the corruption in the family and in the larger society to which the characters belong. However, Weales objected that Williams, like The Glass Menagerie ‘s Tom, had “a poet’s weakness for symbols,” which can get out of hand; he argued that in Suddenly Last Summer, Violet Venable’s garden does not grow out of the situation and enrich the play. Sometimes, Cohn observed, a certain weakness of symbolism “is built into the fabric of the drama.”

Critics favorable to Williams have agreed that one of his virtues lay in his characterization. Those “superbly actable parts,” Atkinson stated, derived from his ability to find “extraordinary spiritual significance in ordinary people.” Cohn admired Williams’s “Southern grotesques” and his knack for giving them “dignity,” although some critics have been put off by the excessive number of such grotesques, which contributed, they argued, to a distorted view of reality. Commentators have generally concurred in their praise of Williams’s talent in creating credible female roles. “No one in American drama has written more intuitively of women,” Clurman asserted; Gassner spoke of Williams’s “uncanny familiarity with the flutterings of the female heart.” Kerr in The Theatre in Spite of Itself expressed wonder at such roles as that of Hannah in The Night of the Iguana, “a portrait which owes nothing to calipers, or to any kind of tooling; it is all surprise and presence, anticipated intimacy. It is found gold, not a borrowing against known reserves.” Surveying the “steamy zoo” of Williams’s characters with their violence, despair, and aberrations, Stang commended the author for the “poetry and compassion that comprise his great gift.” Compassion is the key word in all tributes to Williams’s characterization. It is an acknowledgment of the playwright’s uncanny talent for making audiences and readers empathize with his people, however grotesque, bizarre, or even sordid they may seem on the surface.

Although they have granted him compassion, some of his detractors maintain that Williams does not exhibit a clear philosophy of life, and they have found unacceptable the ambiguity in judging human flaws and frailties that is one of his most distinctive qualities. For them, one difficulty stems from the playwright’s recognition of and insistence on portraying the ambiguity of human activities and relationships. Moral, even puritanical, though he might be, Williams never seems ready to condemn any action other than “deliberate cruelty,” and even that is sometimes portrayed as resulting from extenuating circumstances.

In terms of dramatic technique, those who acknowledge his genius disagree as to where it has been best expressed. For Jerold Phillips, writing in the Dictionary of Literary Biography Documentary Series, Williams’s major contribution lay in turning from the Ibsenesque social problem plays to “Strindberg-like explorations of what goes on underneath the skin,” thereby freeing American theater from “the hold of the so-called well-made play.” For Allan Lewis in American Plays and Playwrights of the Contemporary Theatre, he was a “brilliant inventor of emotionally intense scenes” whose “greatest gift [lay] in suggesting ideas through emotional relations.” His preeminence among dramatists in the United States, Jean Gould wrote in Modern American Playwrights, resulted from a combination of poetic sensitivity, theatricality, and “the dedication of the artist.” If, from the beginning of his career, there were detractors who charged Williams with overuse of melodramatic, grotesque, and violent elements that produced a distorted view of reality, Kerr, in The Theatre in Spite of Itself, termed him “a man unafraid of melodrama, and a man who handles it with extraordinary candor and deftness.”

Other commentators have been offended by what Bentley termed Williams’s “exploitation of the obscene”: his choice of characters—outcasts, alcoholics, the violent and deranged and sexually abnormal—and of subject matter—incest, castration, and cannibalism. Williams justified the “sordid” elements of his work in a Conversationsinterview when he asserted that “we must depict the awfulness of the world we live in, but we must do it with a kind of aesthetic” to avoid producing mere horror.

Another negative aspect of Williams’s art, some critics argued, was his theatricality. Gassner asserted in Directions in Modern Theatre and Drama that Kazan, the director, avoided flashy stage effects called for in Williams’s text of The Glass Menagerie, but that in some plays Kazan collaborated with the playwright to exaggerate these effects, especially in the expressionistic and allegorical drama Camino Real. In a Conversations interview, Williams addressed this charge, particularly as it involved Kazan, by asserting, “My cornpone melodrama is all my own. I want excitement in the theater. . . . I have a tendency toward romanticism and a taste for the theatrical.”

Late in his career, Williams was increasingly subject to charges that he had outlived his talent. Beginning with Period of Adjustment, a comedy generally disliked by critics, there were years of rejection of play after play. By the late 1960s, even the longtime advocate Atkinson observed that in “a melancholy resolution of an illustrious career” the dramatist was producing plays “with a kind of desperation” in which he lost control of content and style. Lewis, accusing Williams of repeating motifs, themes, and characters in play after play, asserted that in failing “to expand and enrich” his theme, he had “dissipated a rare talent.” Gilman, in a particularly vituperative review titled “Mr. Williams, He Dead,” included in his Common and Uncommon Masks: Writings on Theatre, 1961-1970, charged that the “moralist,” subtly present in earlier plays, was “increasingly on stage.” Even if one granted a diminution of creative powers, however, the decline in Williams’s popularity and position as major playwright in the 1960s and 1970s can be attributed in large part to a marked change in the theater itself. Audiences constantly demanded variety, and although the early creations of the playwright remained popular, theatergoers wanted something different, strange, exotic. One problem, Kerr pointed out, was that Williams was so good, people expected him to continue to get better; judging each play against those which had gone before denied a fair hearing to the new creations.

The playwright’s accidental death came when his career, after almost two decades of bad reviews and of dismissals of his “dwindling talents,” was at its lowest ebb since the abortive 1940 production of Battle of Angels. Following Williams’s death, however, the inevitable reevaluation began. Bigsby, for example, found in a reanalysis of the late plays more than mere vestiges of the strengths of earlier years, especially in Out Cry,an experimental drama toward which Williams felt a particular affection. Some of those who had been during his last years his severest critics acknowledged the greatness of his achievement. Even Simon, who had dismissed play after play as valueless repetitions created by an author who had outlived his talent, acknowledged in New York that he had underestimated the playwright’s genius and significance. Williams was, finally, viewed by formerly skeptical observers, as a rebel who broke with the rigid conventions of drama that had preceded him, explored new territory in his quest for a distinctive form and style, created characters as unforgettable as those of Charles Dickens, Nathaniel Hawthorne, or William Faulkner, and lifted the language of the modern stage to a poetic level unmatched in his time.

Posthumous publications of Williams’s writings—correspondence and plays among them—show the many sides of this complex literary legend. Five o’Clock Angel: Letters of Tennessee Williams to Maria St. Just, 1948-1982 takes its title from the name the author gave to Russian-born actress and socialite Maria Britneva, later Maria St. Just, “the confidante Williams wrote to in the evening after his day’s work—his ‘Five o’Clock Angel,’ as he called her in a typically genteel, poetic periphrasis,” noted Edmund White in a piece for the New York Times Book Review. These letters, White added, allow readers “to see the source of everything in his work that was lyrical, innocent, loving, and filled with laughter.” Among the other Williams works published posthumously is Something Cloudy, Something Clear. A play first produced in 1981 and published in 1995, Something Cloudy, Something Clear recounts the author’s homosexual relationship with a doomed dancer in Provincetown. Homosexuality—this time in a violent context—also takes center stage in Not about Nightingales, a tale of terror in a men’s prison. Actress Vanessa Redgrave reportedly played a key role in bringing this early play—written circa 1939—to the London stage in 1998.

Whatever the final judgment of literary historians on the works of Tennessee Williams, certain facts are clear. He was, without question, the most controversial American playwright, a situation unlikely to change as the debate over his significance and the relative merits of individual plays continues. Critics, scholars, and theatergoers do not remain neutral in regard to the man or his work. He is also the most quotable of American playwrights, and even those who disparage the highly poetic dialogue admit the uniqueness of the language he brought to modern theater. In addition, Williams has added to dramatic literature a cast of remarkable, memorable characters and has turned his attention and sympathy toward people and subjects that, before his time, had been considered beneath the concern of serious authors. With “distinctive dramatic feeling,” Gassner said in Theatre at the Crossroads, Williams “made pulsating plays out of his visions of a world of terror, confusion, and perverse beauty.” As a result, Gassner concluded, Williams “makes indifference to the theater virtually impossible.”